Sport and Competition

Flip the Script: Turning Naysayer Put-Downs into Rocket Fuel

Naysayers can become a powerful source of motivation, if you flip the script.

Posted December 21, 2017

What makes some people more resilient and Teflon-coated when it comes to not letting naysayer's scorn make them feel "less than" or crippled by fear of failure? This has become a million-dollar question for me lately. My 10-year-old is in middle school and I've begun to observe some nasty social dynamics that make me want to immunize my daughter against the ickiness of her “mean girl” peers.

In general, I take a hands-off approach and don't intervene directly in my daughter's social life. Common sense, expert advice, and anecdotal evidence all suggest that kids need to fine-tune personalized coping skills for dealing with adversity through real-world practice. Being an overprotective helicopter parent who shields my daughter from any type of hardship seems like the quickest way to instill "learned helplessness."

So, whenever my daughter is upset about her social life or feeling dejected by some type of frenemy behavior, I listen closely as she explains what's going on and give her a big hug,...Then, I usually share a personal story of being in a similar situation at her age coupled with some actionable advice on how I've learned to cope with negative people throughout my life.

More often than not, I find myself reciting some quotation that addresses my daughter's current situation. Over the years, I’ve memorized countless quotes and sayings that I've also road-tested as an effective way to flip the script in my head and maintain an ideal “athletic mindset” during sports training and competition.

Two recent examples that came up with my daughter were a quote from Maya Angelou, who once said, “The quality of strength lined with tenderness is an unbeatable combination." And the Alice Walker poem “Expect Nothing. Live Frugally on Surprise,” which I find myself reciting to my daughter on a somewhat regular basis these days. Both of these capture the psychological essence of being a hybrid between a sensitive "orchid" and resilient "dandelion." This seemingly paradoxical state-of-mind is something I strive for on a daily basis.

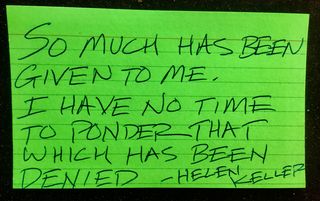

As an ultra-endurance athlete, I kept my antennae up for random quotations, poems, mantras, or any saying that struck an emotional chord and held a refreshing kernel of insight. Through trial and error, I also developed a somewhat sacralized ritual of scribbling these words down on fluorescent green notecards with a classic hexagonal blue Bic pen. Over the decades, I've amassed hundreds of green notecards covered with my illegible chicken scratch. These cards have a lot of sentimental value. I keep them stored in a special wooden box.

At the zenith of my athletic training and sports competition, I kept all of these notecards in mountainous stacks next to my bed. Prior to falling asleep, I’d flip through a few of the cards, memorize the phrase, and subconsciously weave the meaning behind the words into the narrative of my dreams.

Then, whenever I found myself in a situation where I needed some inspiration or guidance, my subconscious mind would scroll through all the cards like a Rolodex. Inevitably, some words of wisdom would pop into my head that hit the nail on the head and were just what I needed at that moment to flip the script of a negative explanatory style.

In many ways, I credit this arsenal of quotations as the key to my athletic success. This is why I infused hundreds of quotations as signposts between the paragraphs of my first book, The Athlete’s Way: Sweat and the Biology of Bliss (St. Martin's Press).

Getting back to the original question of “What makes some people more resilient to naysayers than others?” The other day I stumbled on an interview with Bruce Springsteen, who is one of my all-time favorite musicians and mentors as a human being. During the interview, Anthony Mason asked Bruce “Where do you think your drive comes from?” Springsteen replied, “I believe every artist had someone who told them that they weren’t worth dirt and someone who told them that they were the second coming of the baby Jesus, and they believed ‘em both. That's the fuel that starts the fire."

The mindset captured in this quotation was a Eureka! moment for me. In reflecting on where my own drive comes from, I realized that I unwittingly morph all of the naysayers in my life into rocket fuel that gives me energy and chutzpah to push myself ever higher. This ethos is summed up by a phrase on my favorite fridge magnet:

"Tell me I can't, then watch me work twice as hard to prove you wrong."

Instead of breaking me down, I flip the script so that all the negativity and doubt of the naysayers in my life becomes an inspirational chorus inside my head. I know. It requires some psychological acrobatics and imagination to flip the script and change your explanatory style 180 degrees. But, like anything in life, this skill can be mastered through practice, practice, practice.

Obviously, certain types of abuse and traumatic events go far beyond simply changing your attitude or flipping the script as a way to cope. That being said, turning an underminer into a source of motivation takes away their power and puts it within the locus of your control.

Who are the most influential naysayers in your life? For me, the two most life-changing naysayers during my formative years were my dean at boarding school who chastised me for being a "sissy" and my father who inadvertently made me feel like a "dumb jock."

I know the "sissy/dumb jock" combination may seem like an oxymoron. But, during my early adolescence, my parents' marriage fell apart. Dad moved overseas. I felt abandoned and became a pothead who avoided participating in sports at all costs. Later on, when I was seventeen, I metamorphasized from being a completely unathletic "98-pound weakling" into someone with the eye-of-the-tiger who was obsessed with working out.

Through the lens of the aforementioned Springsteen quote, my father believed in a somewhat hubristic way that I was the “second coming of the baby Jesus” when it came to athleticism. As a young tennis player, he would harp on the fact that I had “cerebellar smarts” and boast about my “athletic genius.” Conversely, my older sister was the “cerebral genius" in dad's eyes and he bragged about her “book smarts.”

For some paternal background: My dad was a textbook Type-A, super-achiever who set completely unrealistic expectations for his kids. My father was a Harvard neurosurgeon, world-renowned neuroscientist, champion tennis player, and wrote a book called The Fabric of Mind (Viking). Obviously, he had a combination of both intellectual smarts and athletic prowess. Along this line, my father applied the framework of his “cerebrum-cerebellum split-brain model” to me and my older sister. In doing so, he unintentionally made each of us feel like we only had half a brain and were somehow less than perfect.

I know my dad had the best intentions. Also, he was sort of between a rock and a hard place because I was a very rebellious kid, hated school, never studied, and got terrible grades. The only booby-prize was for him to try and be supportive by subliminally implying 'It’s OK that you’re not that smart, Chris. Because you’re so good at sports!'

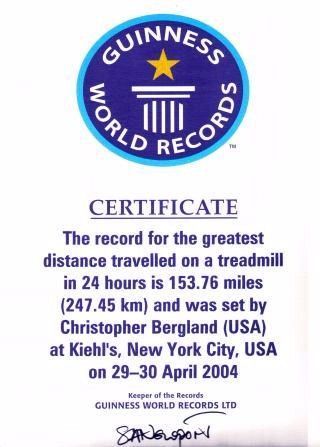

This is where my father being a naysayer about my intellectual capacity was a blessing in disguise which helped me reinvent myself after I retired from sports. Because my dad never thought I was particularly cerebral, after I broke a Guinness World Record by running 153.76 miles in 24 hours on a treadmill, I decided to get a book deal. My prime motivating force was to prove to my father that I wasn't just a "dumb jock." Of course, I had no idea at the time how difficult it is to write a book...But I applied my athletic mindset to the challenge and was so determined to prove him wrong that I never gave up. (Yes, having a chip on my shoulder has served me well over the years.)

Serendipitously, my father died unexpectedly of a heart attack just a few weeks after my first book was published. When they found his body, he was in a Lay-Z-Boy chair reading the Sunday New York Times surrounded by stacks of my hardcover book. Unbenounced to me, dad had bought a whole box of my book to give to family and friends. Picturing my father on his deathbed always makes me verklempt. It also inspires me to keep researching and writing about neuroscience in his honor. I'll probably spend the rest of my life trying to make my dad proud.

The other example of a pivotal naysayer is my dean at Choate Rosemary Hall in Wallingford, Connecticut who liked to make fun of me for being a sissy. He called me "Chrissy." Interestingly, I actually get a kick out of being called "Chrissy" these days. Reclaiming this nickname as something I embrace wholeheartedly is another example of flipping the script of a naysayer's scorn and making it something uplifting.

When I was trapped at Choate in the early 1980s, it was a really messed up place; especially if you were a gay teen, like me. The current administration at CRH knows all the nitty-gritty details of my traumatic experiences in Wallingford. They've apologized and I accept their apology. (For more on this topic, check out the New York Times article: "Choate Rosemary Hall, a Very Private School, Publicly Catalogs Its Sins.")

Of course, I would never wish the psychological torment that I experienced at boarding school on my worst enemy. That said, being bullied by my omnipotent dean at a very vulnerable period in life forced me to develop coping mechanisms in order to survive.

When I compiled the book acknowledgments for The Athlete’s Way, I purposely made the final “thank you” to my dean as a way to have the last word and move on. I wrote:

“Mr. Yankus (my dean in high school): Thank you for trying to convince me that I would amount to nothing. Whether it was reverse psychology or not, you forced me to make something of my life just to prove you wrong. I needed to succeed at first just to spite you. I didn't ever want you to be able to say, "I told you so." My resentment toward you was the seed that sparked my athletic conversion. At the end of the day, I am grateful to you for being so hard on me, even though it really sucked at the time. Thank you.”

Again, there is an important caveat: I want to make it crystal clear that reframing bullies and naysayers to be a “blessing in disguise” is in no way condoning that type of behavior. The reason I'm exploring this "flip the script" coping mechanism in detail is because I've found it helpful and it's an explanatory style that doesn’t get much airtime.

In closing, here’s a bullet list of three ways to flip the script and turn “naysayer scorn into yeasayer mojo." These techniques have worked for me both on and off the court. Maybe they’ll work for you, too?

- Anthems, Mantras, and Role Models: Create soundtracks and playlists of songs that inspire you and blast them in your headphones at top volume on a regular basis. Jot down any quotations or phrases that resonate with you on a deep level and memorize them. Put pictures of your role models and personal heroes on the fridge door or any place else you'll frequently see their likeness.

- Create a Quirky Superhero Alter-Ego: Use your imagination to create an alter-ego that you aspire to become through hard work. Include some “wabi-sabi” flaws and chinks in the armor of your alter-ego to keep it real. Amalgamate a blend of all the character traits you admire in others. Then, “fake it till you make it.”

- Romanticize the Scrappiness and Perseverance of Being an Underdog: Everybody roots for the underdog. Try to avoid feeling sorry for yourself and falling into the “learned helplessness” trap by romanticizing the "underdog" struggle as something valiant. Even when you feel on top of the world, never rest on your laurels and keep pretending you're an underdog. Play up the “comeback kid” aspects of being a "little ole ant" and always strive to prove the naysayers wrong.