Health

Letting Kids Run Wild Could Improve Academic Performance

Physical fitness and agility are linked to bigger brains and better test scores.

Posted November 23, 2017

Long before scientists knew that aerobic exercise increases the amount of gray matter in the brain, Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888) prophetically observed a link between physical fitness, motor-skill agility, and a more "lively" brain. Over a century ago, the author of Little Women described the benefits of “running wild” in the woods at her family home near Walden Pond or chasing a hoop around Boston Common in the mid-19th century. Louisa May Alcott once said:

"Active exercise was my delight from the time when a child of six I drove my hoop around the Common without stopping, to the days when I did my twenty miles in five hours and went to a party in the evening. I always thought I must have been a deer or a horse in some former state, because it was such a joy to run. No boy could be my friend until I had beaten him in a race, and no girl if she refused to climb trees, leap fences, and be a tomboy . . . My wise mother, anxious to give me a strong body to support a lively brain, turned me loose in the country and let me run wild."

Recently, a cutting-edge study was published in the journal NeuroImage which corroborates that the Alcott mother-daughter dyad was right about the link between active exercise and a “lively brain.” The researchers from University of Granada (UGR) found that children with better physical fitness and motor-speed agility also possessed greater volume of gray matter and did better in school.

To the best of their knowledge, the researchers believe this is the first time in history that brain imaging has identified a correlation between a child’s level of cardiorespiratory fitness, motor speed-agility, brain structure, and academic performance.

This research is part of the ActiveBrains Project, which is a randomized clinical trial involving more than 100 overweight/obese children led by Francisco B. Ortega. "Our work aims at answering questions such as whether the brain of children with better physical fitness is different from that of children with worse physical fitness and if this affects their academic performance," Ortega explained in a statement. "The answer is short and forceful: yes, physical fitness in children is linked in a direct way to important brain structure differences, and such differences are reflected in the children's academic performance."

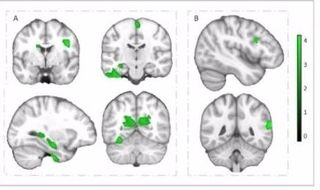

Ortega and his UGR colleagues have identified that physical fitness in children (especially aerobic capacity and motor ability) is associated with a greater volume of gray matter in several cortical and subcortical brain regions.

More specifically, aerobic capacity was correlated with greater gray matter volume in frontal regions (premotor cortex and supplementary motor cortex), subcortical regions (hippocampus and caudate nucleus), temporal regions (inferior temporal gyrus and parahippocampal gyrus) and the calcarine cortex. All of these regions are important for the executive function as well as for learning, motor and visual processing.

The UGR research also identified a link between motor-skill ability and greater gray matter volume in two regions essential for language processing and reading: the inferior frontal gyrus and the superior temporal gyrus.

According to Irene Esteban-Cornejo, a postdoctoral researcher at UGR and the main author of this paper: “Gray matter volume in the cortical and subcortical regions influenced by physical fitness improves in turn the children's academic performance. Physical fitness is a factor that can be modified through physical exercise, and combining exercises that improve the aerobic capacity and the motor ability would be an effective approach to stimulate brain development and academic performance in overweight/obese children."

The researchers see their latest research as a clarion call for policymakers overseeing educational and public health institutions. They state this call-to-action emphatically:

"We appeal both to politicians, who make educational laws that are increasingly more focused on instrumental subjects, and to teachers, who are the final link in the chain and teach Physical Education day after day. School is the only entity that gathers every children in a mandatory way for a period of at least 10 years, and as such, it's the ideal context for applying such recommendations.”

The authors of this study conclude by reiterating that their ActiveBrains project is "at the disposal of educational and public health institutions for talking about possible measures and putting them into action." Hear, hear!

References

Esteban-Cornejo, Irene, Cristina Cadenas-Sanchez, Oren Contreras-Rodriguez, Juan Verdejo-Roman, Jose Mora-Gonzalez, Jairo H. Migueles, Pontus Henriksson, Catherine L. Davis, Antonio Verdejo-Garcia, Andrés Catena, Francisco B. Ortega. A whole brain volumetric approach in overweight/obese children: Examining the association with different physical fitness components and academic performance. The ActiveBrains project. NeuroImage (2017) DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.08.011

Cadenas-Sánchez, Cristina, José Mora-González, Jairo H. Migueles, Miguel Martín-Matillas, José Gómez-Vida, María Victoria Escolano-Margarit, José Maldonado et al. "An exercise-based randomized controlled trial on brain, cognition, physical health and mental health in overweight/obese children (ActiveBrains project): Rationale, design and methods." Contemporary Clinical Trials (2016) DOI: 10.1016/j.cct.2016.02.007