Stress

Chronic Stress Discombobulates Gut Microbiome Communities

Gut microbiome communities become unpredictable when someone is in distress.

Posted August 25, 2017

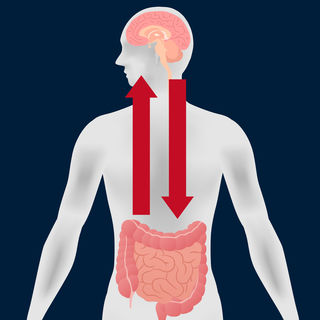

Each of us has trillions of microorganisms and diverse bacterial communities—commonly referred to as microbiome or gut microbiota—residing in our gastrointestinal tract at any given time. There is growing evidence that unique combinations of gut microbiome colonies play a mysterious yet significant role in many aspects of our mental health—ranging from psychological resilience to neuropsychiatric disorders—and vice versa. As part of a bidirectional gut-brain axis, the vagus nerve facilitates communication between our psychological states of mind and the visceral state of our gut microbiome.

When people are feeling healthy, relaxed, and safe, their gut microbiome communities generally work together harmoniously in a predictable symbiotic manner, according to a new study. However, the Oregon State University researchers found that when someone is under stress, his or her gut microbiome communities become discombobulated and behave erratically, in ways that are unpredictable and vary from person to person. This study, “Stress and Stability: Applying the Anna Karenina Principle to Animal Microbiomes,” was published online August 24 in Nature Microbiology.

Leo Tolstoy famously said: "All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way." After realizing how unpredictably each individual's gut microbiome communities responded during "unhappy" stressful situations, the research team coined their discovery the "Anna Karenina principle" in honor of Tolstoy's dictum. In the study abstract, the authors write:

"The result is an ‘Anna Karenina principle’ for animal microbiomes, in which dysbiotic individuals vary more in microbial community composition than healthy individuals—paralleling Leo Tolstoy's dictum that “all happy families look alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way." We argue that Anna Karenina effects are a common and important response of animal microbiomes to stressors that reduce the ability of the host or its microbiome to regulate community composition."

For this study, the researchers set out to identify microbiome changes triggered by stressful perturbations that cause gut microbiome communities to transition from a stable “symbiotic” state to an unstable “dysbiotic” state. As mentioned earlier, when people are not experiencing psychological or physical distress, it is much easier to predict symbiotic and harmonious microbiome behavior in their GI tract.

In a statement, senior author Rebecca Vega Thurber—who founded the Rebecca Vega Thurber Lab at OSU—offered another metaphor to explain what she and her collaborators have discovered: "When healthy our microbiomes look alike, but when stressed each one of us has our own microbial snowflake. You or I could be put under the same stress, and our microbiomes will respond in different ways—that's a very important facet to consider for managing approaches to personalized medicine."

The Microbiome-Gut-Brain Axis Is a Bidirectional Feedback Loop

On August 22, researchers in Germany published a comprehensive review of recent microbiome-gut-brain axis clinical studies from around the globe in the journal Frontiers in Psychiatry. One important takeaway from their analysis was that the vagus nerve plays a pivotal role in the bidirectional communication between gut and brain. This means that your vagus nerve sends messages about psychological states of mind from the top-down (brain⇒gut) and also receives visceral "gut instincts" and physiological feedback—such as having butterflies in your stomach—from the bottom-up (gut⇒brain).

The latest findings from Thurber et al. on how stress uniquely impacts our microbiome communities dovetail with many of the other findings cited in recent microbiome-gut-brain axis research. For example, researchers at Harvard Medical School recently reported that elite-level athletes who stayed calm, cool, and collected during stressful sports competitions shared common gut microbiome traits. The HMS researchers believe there might be a correlation between mental toughness and gut microbiome.

Based on the latest empirical evidence, one could speculate that taking a dual pronged approach that addresses psychological well-being from the "bottom-up" by identifying ways to optimize microbiome through diet or probiotics combined with a "top-down" approach that focuses on conscious ways to stimulate parasympathetic vagus nerve responses to inhibit "fight-flight-or-freeze" stress responses could be a winning formula for maintaining microbiome symbiosis.

These are exciting times for gut microbiota research. Pioneering discoveries about how specific microbiome strains adapt to various psychosocial stressors, diet, mindset, and environment are being published at breakneck speed. That said, more research is needed before clinical applications and best practices for of all of these findings can be implemented most effectively.

If you'd like to learn some practical ways to engage your vagus nerve and maintain grace under pressure during times of distress, check out my nine-part, "Vagus Nerve Survival Guide to Combat Fight-or-Flight Urges," series.

References

Jesse R. Zaneveld, Ryan McMinds, Rebecca Vega Thurber. Stress and stability: applying the Anna Karenina principle to animal microbiomes. Nature Microbiology. Published online August 24, 2017. DOI: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.121

“I Am I and My Bacterial Circumstances”: Linking Gut Microbiome, Neurodevelopment, and Depression by Juan M. Lima-Ojeda, Rainer Rupprecht and Thomas C. Baghaiin. Frontiers in Psychiatry. Published online August 22, 2017. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00153