Neuroscience

The Split-Brain: An Ever-Changing Hypothesis

Tracing the genesis and evolution of a cocreated father & son split-brain model.

Posted March 30, 2017

My late father, Richard Bergland (1932-2007), was born near the Badlands of Montana to Norwegian parents who were missionaries at the time. Although my dad grew up very poor, he did have access to a public tennis court. Once my dad got his hands on a used tennis racket, he spent most of his free time as a kid practicing his serve and hitting a tennis ball against a backboard. In high school, he became the Montana State Tennis Champion, which earned him a scholarship to Wheaton College.

After college, my father attended Cornell Medical School in Manhattan where he played squash regularly with legendary neurosurgeon Bronson Ray (who was mentored by brain surgery pioneer Harvey Cushing). Ray took my dad under his wing and groomed him as a neurosurgical protégé. Racket sports played a pivotal role in my father's life. He would often say, "Of this, I am absolutely certain. Becoming a neurosurgeon was a direct consequence of my eye for the ball."

I was born at New York Hospital on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in 1966. At the time, my father was still a resident at Cornell. We lived in Phipps Residence House on York Avenue. Before I was born, my mother worked as a personal secretary for René Dubos at Rockefeller Institute kitty-corner from our apartment building. My mom typed the early drafts and revisions of his 1969 Pulitzer Prize-winning book, So Human an Animal: How We Are Shaped by Surroundings and Events. Dubos and my mother became lifelong friends. My older sister, Renée, is named after René Dubos.

As I was growing up, my father put a lot of pressure on me to excel in sports and to become a champion, just like him. I started playing tennis as soon as I could hold a racket. My dad was my primary tennis coach. Throughout my childhood and early adolescence, I strived to make my father proud of me, dreamed of becoming the next Björn Borg, and was determined to win Wimbledon some day.

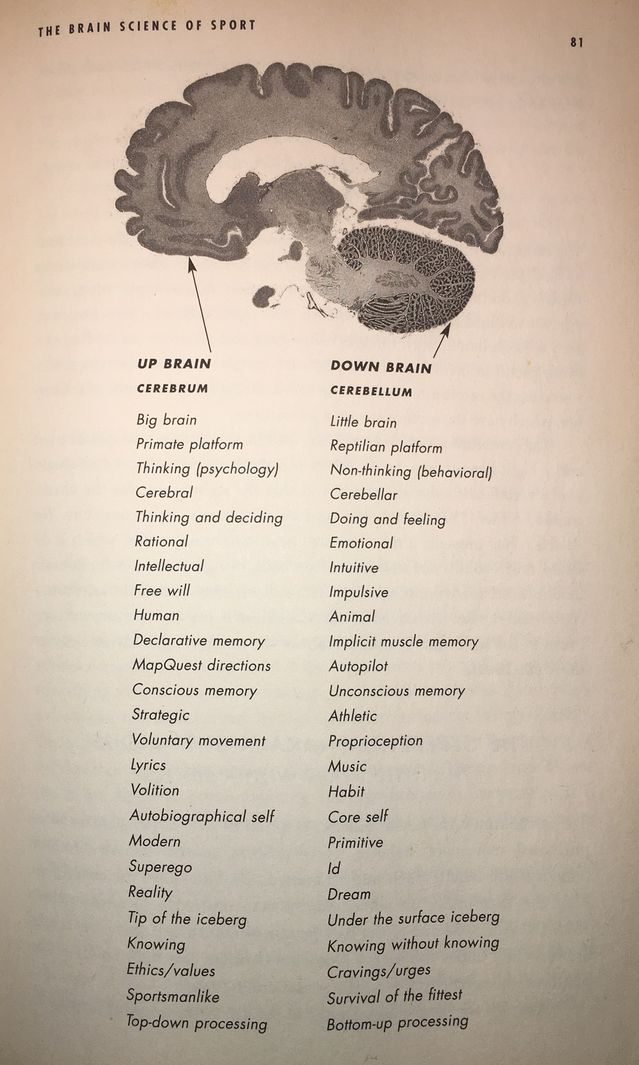

As a neuroscience-based tennis coach, my father would say things to me like, “Chris, think about hammering and forging the muscle memory of the Purkinje cells in your cerebellum with every stroke.” My father was obsessed with the cerebellum (Latin for “Little Brain”) being the seat of athletic genius and the cerebrum (Latin for “Brain”) being the seat of intellectual “cerebral” intelligence. (Cerebellar is the sister word to cerebral and means “relating to or located in the cerebellum.")

My father was a freakish superachiever who had an abundance of both cerebral intelligence as well as extraordinary cerebellar athletic prowess. Interestingly, he always thought brain surgery was much more cerebellar than cerebral. That said, neurosurgery obviously requires a blend of retaining neuroscience knowledge in the cerebral cortex and mastering the fine-tuned motor skills of the cerebellum.

In a somewhat narcissistic and pressure-cooker way, my dad really wanted all of his kids to be a reflection of his own cerebral and cerebellar excellence by getting straight A's and becoming varsity athletes. He set unrealistic expectations. The bar was always very high in terms of living up to his "need for achievement" standards in order to feel worthy of love and belonging. Since I was a kid, I've always felt that I'm a day away from where I need to be, which is both a blessing and a curse.

Unfortunately, my older sister was born very nearsighted in one eye and never had a terrific eye for the ball on the tennis court. She overcompensated by completely immersing herself in reading books and being top of her class. Renée read War and Peace in the fourth grade, got perfect double-800 scores on her SATs, and attended Phillips Exeter Academy boarding school. Fittingly, as a cerebral powerhouse with off-the-charts “book smarts,” she attended St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland where the curriculum is based on the “Great Books.”

On the flip side, I was a horrible student and got terrible grades. I had trouble sitting still in class and hated school. But, I was good at tennis. My father inadvertently made me and my older sister feel somewhat 'less than' in different ways by constantly complimenting Renée for her "cerebral" book smarts and me for my "cerebellar" talents. I know my dad probably had the best intentions, but singling us out for having "failed" in some way by only having limited types of "intelligence" made us both feel like we had "half a brain" under a cerebral-cerebellar model.

The good news: As an anecdotal affirmation of Carol Dweck’s "growth mindset" hypothesis, my sister and I each evolved to have a healthy blend of both cerebral "book smarts" and cerebellar "athletic prowess," proving that mindset is never fixed. My little sister, Sandy, on the other hand, was always a perfect blend of both athleticism and test-taking intelligence. She went on to become a Boeing 777 pilot for FedEx and consistently made my dad the proudest.

Speaking of making my father proud, in the early 1980s I realized I was gay. At the time, I was trapped at a stodgy boarding school in Wallingford, Connecticut called Choate Rosemary Hall. My dean at Choate was also the varsity football and baseball coach. Early on, my dean singled me out as being a “sissy” and chastised me in a way that made me lose all interest in sports.

I began binge drinking and doing tons of drugs. In the early ‘80s, Choate embodied the Bright Lights, Big City zeitgeist of privileged "Preppy Handbook" substance abuse. For example, my prep school classmates would go on to make the front page of the New York Times for getting busted at JFK airport while trying to smuggle $300,000 of cocaine from Venezuela back to campus.

Although I was a party animal, the shame I felt about being gay fueled my boarding school substance abuse in a way that made me feel increasingly socially isolated and hollow inside. When I was sixteen, I fell into a suicidal Major Depressive Episode (MDE) exacerbated by my excessive intake of drugs and alcohol. I felt dead inside. I listened to Pink Floyd’s album The Wall incessantly. Of course, “Comfortably Numb” was my anthem.

Luckily, on a rainy Sunday night in 1983, when I was back in Boston on a school break, my best friend twisted my arm to go see Madonna (who wasn't famous yet) perform at a small gay nightclub on Lansdowne St. called the Metro. Madonna’s exuberance and joie de vivre was so contagious it flipped a switch in my brain. Her joy-filled music and chutzpah single-handedly snapped me out of my cynical hopelessness.

The next morning, I went to directly to Strawberries record store in Kenmore Square and bought Madonna's first album. By the following afternoon, I was jogging around the Chestnut Hill reservoir with my Walkman blasting “Holiday” at top volume and I felt my spirits start to rise for the first time in years. It was a conversion experience for me. The combination of breaking a sweat while listening to music on my Walkman made me feel as if I’d been born again. I stopped doing drugs completely and became a go-getter who was eager to seize the day.

In the Fall of 1984, I enrolled at Hampshire College, which is a small liberal arts school in Amherst, Massachusetts with no tests and no grades. Based on my self-perceived lack of “cerebral” academic intellect at the time, it was a perfect fit. Also, I intuitively clicked with the pedagogy of the school motto Non Satis Scire (Latin for “To know is not enough”) which encourages students to explore any topic that gets your juices going and then to connect the dots in new and useful ways in a final dissertation called a “Division Three.”

As part of my studies at Hampshire, I spent a semester at Paramount Studios working as an intern with Mary Hart and John Tesh on Entertainment Tonight. Pursuing this internship was motivated by my love of pop culture and my curiosity to see the underbelly of Hollywood up close. Then, I went to India for a Jan. Term to investigate the impact of American media and “Mickey Mouse” on India’s indigenous culture. Traveling overseas alone as a college student was a quixotic adventure and rite of passage. Especially, because I was fascinated with Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey archetypes and romanticized exploring exotic far away lands and returning home to write about what I'd learned in my travels to unmapped places.

During this period, I grew my hair into a Hippie shag with lots of curls and mini blond dreadlocks (which drove my father crazy). I also practiced yoga and meditation religiously, as a way to create altered “trance-like” states of consciousness. This headspace intrigued me as a brain science phenomenon. Because my father was a neuroscientist, I’ve always considered myself a human lab rat in terms of looking at the impact of drugs, alcohol, exercise, meditation, and perceived social isolation on my own neurobiology.

Around this time, my father was writing the manuscript for his book The Fabric of Mind (Viking). Much of this book was inspired by my dad’s laboratory experiments which explored the electrical, chemical, and architectural changes that occur in animals depending on what they’re doing. For example, as a neuroscientist my dad would create animal experiments to test changes in neurotransmitters and brain waves when sheep were sleeping, walking on a treadmill, eating, having sex, etc.

As a neuroscientist and chief of neurosurgery at Harvard Medical School's BIDMC in the late 1970s and early 1980s, my dad was often approached by pop psychology writers interested in popularizing the notion of the "right brain" as the seat of creativity. Much to his chagrin at later points in his life, he unwittingly participated in promoting the “right brain” myth. (For example, my father was the medical expert for Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. I love this book for its artistic inspiration. But it isn't 100 percent empirically correct from a strictly neuroscientific perspective based on what we know now about the right cerebral hemisphere.)

Later in his life, my father regretted that he'd publicly identified himself with the "right brain" being the seat of creativity. Additionally, I think it damaged his credibility amongst scientific peers. But, it was too late. That genie was out of the bottle. As much as my dad tried to find a megaphone loud enough to reverse the juggernaut of most people associating the right brain of the cerebral cortex with creativity, it was futile.

When my father retired from neurosurgery in the late 1990s, he mellowed out and our relationship began to mend. That said, it was heartbreaking to see him struggle to find a sense of purpose and a way to get his most recent visionary ideas about the brain to a general audience or to get his work published in peer-reviewed journals. He was floundering and fell into a dark depression.

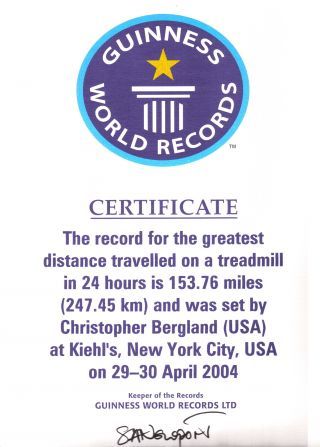

After I broke a Guinness World Record in 2004, I realized that I could kill three birds with one stone by getting a book deal to write about neuroscience and sports. First, I could prove to my dad once and for all that I wasn’t a “dumb jock.” (Yes, I still have a chip on my shoulder) Second, I could use his neuroscience expertise to make sure my writing was empirically accurate while advancing fresh ideas about how the brain works in a prescriptive way. Third, I could buoy my dad’s spirits and rebuild our father-son relationship, which had become fractured over the years. It was a fantastic collaboration.

As I explain on p. xiii in the introduction to The Athlete’s Way: Sweat and the Biology of Bliss (St. Martin’s Press):

When I was growing, up neuroscience was a constant topic of conversation, and discussions with my father have continued over the years. The Athlete’s Way is based on the hypothesis that humans have two brains: an animal feeling-and-doing brain called the cerebellum (Latin: little brain), and a human thinking-and-reasoning brain called the cerebrum (Latin: brain).

My dad and I refer to this brain model as 'down brain-up brain.' The up brain is the cerebrum based on its position north of the midbrain, which is midway between the two brains. The cerebellum is the down brain, the southern hemisphere in the cranial globe as it were, based on its position south of the midbrain. The simple names down brain-up brain may sound grammatically incorrect but are a direct and cogent response to the 1970s split-brain model of ‘left brain-right brain.'"

Tragically, my father died suddenly of a heart attack just a few weeks after The Athlete’s Way and our revolutionary "up brain-down brain" model was published in hardcover. At my father’s funeral, I made a vow that I would keep my antennae up for any new research on the “little brain” that might help to answer my dad’s never-ending query: “We don’t know exactly what the cerebellum is doing. But whatever it’s doing, it’s doing a lot of it.”

Unfortunately, in the early 21st century, pioneering neuroscience research on the cerebellum was scarce. And I was chomping at the bit to keep researching and writing. So, I decided that I would look into the daily routines of creative greats through the lens of cerebral-cerebellar dynamics to see what role physical activity played in their creative process. I also wanted to investigate anecdotally if exercise increased the odds of someone having a eureka! moment.

My research hypothesis for Origins of Imagination was inspired by the fact that Albert Einstein said of E = mc² “I thought of that while riding my bicycle.” I also knew from my own creative process that aerobic activity always helped me problem solve and come up with new ideas.

One day in 2009, as I was walking home from the gym, I bumped into my friend Maria on Commercial street in Provincetown. Maria is a poet. She asked me what I was up to. I began telling her about all the research I was doing on the daily habits of creative people and how I had a hunch that physical activity was a key to creating ‘superfluidity’ (no friction or viscosity) of thought.

Without missing a beat, Maria looked at me and said, “I ride the elliptical trainer for at least 40 minutes every day. Whenever I start moving my arms and legs back and forth, poetry starts to pour out of me.” As Maria moved her arms and legs back and forth to emulate riding the elliptical, suddenly, I realized that her bipedal motion was engaging all four hemispheres of both the cerebrum and cerebellum. And that the connectivity between ALL FOUR brain hemispheres might be optimizing brain function and lead to fluid intelligence. (It was an Aha! moment for me at the time).

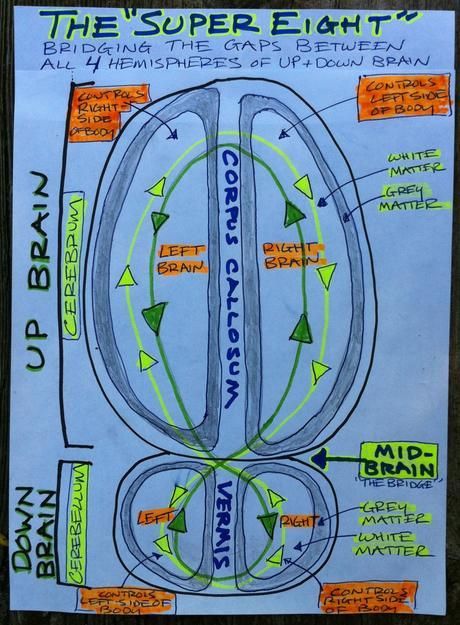

Maria's movements and the link between her daily exercise routine and writing poetry inspired me to draw the sketch you see below. I rushed home and got this very basic illustration down on paper as quickly as I could:

To this day, anytime I look at the sketch above (which I drew almost a decade ago) I continue searching for clues hidden in this "map" that might advance our understanding of the interplay between these various brain regions. With every new scientific study using state-of-the-art technology that teaches us more about the role that the cerebellum plays in cognition, I revisit this map and update the architectural blueprints of the ever-changing Bergland split-brain model in my mind’s eye.

As I sit here writing this Psychology Today blog post in 2017, it’s clear that the functional connectivity between various cortical and subcortical brain regions plays a role in many types of cognitive processes and various cognitive disorders. For example, on March 28 researchers at the University of Iowa reported that delta-wave stimulation of the cerebellum improved frontal cortex functioning of schizophrenia-like thinking in lab rats. (I wrote about this discovery yesterday in a Psychology Today blog post, "Cerebellum Stimulation Influences the Frontal Cortex")

As a work in progress, I realize now that any scientifically accurate sketch of the “Bergland Split-Brain Model” (which emphasizes the functional connectivity and interplay between the cerebellum and cerebral cortex) would also have to include other subcortical brain regions such as the basal ganglia and brainstem. Increasingly, there is growing evidence of a “cerebellum-basal ganglia-cerebral cortex system” that appears to work in concert.

The research focusing on the cerebellum, basal ganglia, and cerebral cortex behaving like triad is still in its infancy. I would try to make a sketch to illustrate how this brain system works in concert, but I’m not a good enough artist to represent the dynamic interplay between these brain regions accurately. That being said, stay tuned for updates on the ever-changing evolution of the somewhat outdated, but still relevant original “up brain-down brain” model my dad and I created together over a decade ago.

References

K L Parker, Y C Kim, R M Kelley, A J Nessler, K-H Chen, V A Muller-Ewald, N C Andreasen, N S Narayanan. Delta-frequency stimulation of cerebellar projections can compensate for schizophrenia-related medial frontal dysfunction. Molecular Psychiatry, 2017; DOI: 10.1038/mp.2017.50

Caligiore, D., Pezzulo, G., Baldassarre, G. et al. Consensus Paper: Towards a Systems-Level View of Cerebellar Function: the Interplay Between Cerebellum, Basal Ganglia, and Cortex. Cerebellum (2017) 16: 203. doi: 10.1007/s12311-016-0763-3