Neuroscience

The Father of Modern Neuroscience Was an Athlete and Artist

Santiago Ramón y Cajal revolutionized neuroscience by making beautiful art.

Posted January 27, 2017

Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852-1934) is considered by many to be the father of modern neuroscience. He was one of the first people to unravel the mysteries of our brain's architecture by making incredibly detailed and beautiful drawings of how individual neurons create tapestry-like neural networks within specific brain regions.

The same images that Cajal captured in his drawings—and shared with the world over a century ago—are now recreated using advanced brain imaging technologies. Tomorrow, his breathtaking artwork goes on display in an American museum for the first time as part of a traveling exhibit that will tour the country in months ahead.

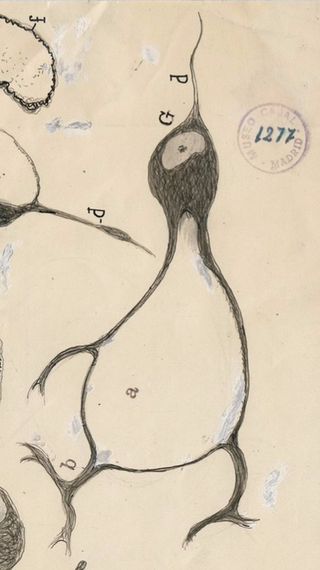

In 1906, Santiago Ramón y Cajal won a Nobel Prize, along with fellow-Spaniard Camillo Golgi, for their collaborative efforts using state-of-the-art slide making techniques (developed by Golgi) to illustrate distinctively separate neurons in the brain. The earliest application of the "Black Reaction" (La reazione nera) technique used silver impregnation to create medical slides of Purkinje neurons and granule cells in the cerebellum (Latin for "little brain").

Using his skills of draughtsmanship and artistry, Cajal was able to bring the neural structures of the cerebellum, and other brain regions, to life on paper, using pen and ink. Cajal's detailed drawings created the foundation of modern neuroanatomy.

Cajal's ability to recreate large-scale illustrations of nerve cell organization within the central and peripheral nervous system allowed him to make these neural networks easy to visualize for both scientists and the general public. To this day, Santiago Ramón y Cajal's timeless illustrations are used in medical textbooks.

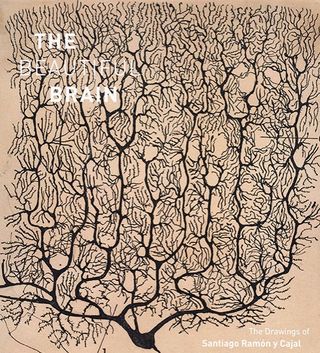

The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal

Yesterday on NPR, All Things Considered aired a segment, "Art Exhibit Celebrates Drawings by the Founder of Modern Neuroscience" about the new traveling art exhibit featuring Cajal's drawings which debuts tomorrow at the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis. The exhibit will be at the Weisman Museum from January 28 through May 14, 2017. Among other stops, the exhibit will open at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT Museum) in the Spring of 2018.

This exhibit features 80 original Cajal sketches side by side with modern-day brain imaging. This juxtaposition shows how ahead of his time Cajal's illustrations were. It took years for a team of American neuroscientists and the Minneapolis Museum to coordinate this traveling exhibition with the Cajal Institute in Madrid and the Spanish government.

Understandably, the Instituto Cajal del Consjo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIS) in Spain is very protective of these priceless works of art with such huge scientific importance. Luckily for all of us around the world, a hardcover coffee-table book, The Beautiful Brain (Abrams) was published this month to complement the Santiago Ramón y Cajal art exhibit that features Cajal's hallmark image of a Purkinje neuron in the cerebellum on the cover.

"Whatever the cerebellum is doing, it's doing a lot of it." — Richard Bergland, M.D.

My father, Richard Bergland, was a neuroscientist, neurosurgeon, and author of The Fabric of Mind (Viking). My dad idolized Santiago Ramón y Cajal and passed his fascination with the life and work of Cajal on to me. My dad was simpatico with Cajal's passion for recreating images of the brain, and his somewhat esoteric obsession with the cerebellum.

Because the cerebellum is only 10 percent of brain volume but houses well over 50 percent of your brain's total neurons, my father would often say, "We don't know exactly what the cerebellum is doing. But whatever it's doing, it's doing a lot of it."

When my father was desperately trying to convince me to go to medical school after college in the late 1980s, he gave me a copy of Santiago Ramón y Cajal's memoir, Recollections of My Life (MIT Press). This is a terrific book that gives the reader an intimate look into the very dynamic and robust mind of a legendary neuroscientist, who was also an artist and athlete.

My father's attempts to persuade me to go into neuroscience by reading Cajal's life story backfired. While reading this book, I identified much more with Cajal's rebellious spirit than the fact that he went on to be a Nobel laureate. Incidentally, one of my favorite passages from the book describes his relationship with his father, who was also a surgeon. On p. 46 of his memoir, Cajal writes:

"My father would have liked to keep watch over me and to chastise me upon the first transgression, but was prevented by his extensive [surgical] practice in the town and adjacent villages . . . In spite of the precaution taken, the devil often tempted. Wherever an opportunity presented itself, we mischief-makers of the school took full advantage of it, celebrating it sometimes with battles staged in the suburbs."

Cajal was notorious for being a rebellious teenager who hated school. He was much more interested in spending time at the gym, lifting weights, practicing gymnastics, taking photographs, making art, etc. than studying. I am cut from the same cloth.

My love of sports and spending time at the gym throughout my adolescence and young adulthood frustrated my father to no end. He would regularly lambast me for not being more cerebral or academic. My dad would constantly nag me by saying things such as, "Chris, there's a very large portion of your brain that you're forgetting to flex. And it's going to turn into mush!!"

I think my dad saw a parallel between himself and Cajal's father (who was also a surgeon). But Santiago's dad was able to convince his free-spirited son to buckle down and pursue a career in neuroscience. As I mentioned earlier, my father failed in his attempts to do the same. Part of me will always feel guilty that I let my father down by deciding to become a professional athlete and not a medical doctor or scientist. In many ways, I've been trying to make up for the disappointment I caused my father ever since I retired from sports.

For example, when I published The Athlete's Way: Sweat and the Biology of Bliss (St. Martin's Press), I included brain images from my father's lab along with a Santiago Ramón y Cajal drawing (similar to the one on the cover of The Beautiful Brain) in a section "Purkinje Cells: The Key to Muscle Memory" on pp. 119-120. In the caption to the Cajal illustration, I wrote:

"The Purkinje cells are beautiful to look at. They look like one tree trunk (the axon) with hundreds of roots. The long extended branches (dendrites) of the Purkinje cell are what allow it to collect input from two hundred thousand other cells. This incredible power of amplification directly connects all the information from your body to your mind."

As a young medical student, my dad worked a lot with medical slides that used the "Black Reaction" of staining. But, later in his life, he would go on to use an electron microscope in his laboratory to create images that looked very much like Cajal's artwork.

My dad loved to make enlarged reprints of his brain images and frame them. He proudly hung his neuroimages on the walls of his office and around our house. As a neuroimaging photographer, my dad believed that massive abstract canvases of any type of brain images wouldn't seem out of place at the Museum of Modern Art.

If my father were alive today, I know he'd be thrilled to see Santiago Ramón y Cajal's artwork being given the credit it deserves by the art world and showcased in American museums.

Please keep your antennae up for "The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal" traveling exhibit coming to a museum or gallery near your hometown sometime later this year or in 2018. I can't wait to see this art exhibit!