Self-Control

Your Brain Can Be Trained to Self-Regulate Negative Thinking

Executive control training alters brain regions linked to emotional regulation.

Posted January 10, 2016 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Different brain areas are activated when one voluntarily chooses to suppress an emotion using mindfulness vs. inhibiting the emotion.

- Non-emotional training that improves the ability to ignore irrelevant information can result in reduced brain reactions to emotional events.

- The greater the problem of emotional regulation one has, the smaller the volume detected in the orbitofrontal cortex.

In recent years, scientists have identified specific brain regions involved in the process of emotional regulation. The latest research shows that conscious training of your "executive control" makes it possible to reshape the architecture of your brain and rewire the neural pathways of your mind. Interestingly, mindfulness research also shows that different brain areas are activated when you choose to regulate or suppress an emotion, compared to when someone instructs your to inhibit an emotion.

To give you a comprehensive overview of the latest research on the brain mechanics of self-regulating negative emotions, I've chosen three recent studies on this topic:

1. Different Brain Areas Are Involved in Emotional Self-Control

In 2013, researchers from the University College London (UCL) Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience and Ghent University discovered that different brain areas are activated when someone voluntarily chooses to suppress an emotion using mindfulness, compared to when he or she was explicitly instructed to inhibit a specific emotion.

The May 2013 study, “Differences Between Endogenous and Exogenous Emotion Inhibition in the Human Brain,” was published in the journal Brain Structure and Function.

For this study, the researchers showed 15 healthy women unpleasant or frightening pictures while using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to scan their brains. Each subject was given a choice to either feel the emotion elicited by the image or to inhibit the emotion by distancing themselves through a conscious act of emotional detachment.

The researchers compared these findings of brain activity to another experiment in which participants were specifically instructed to feel or inhibit their emotions, but not given the option to choose for themselves. In a press release, lead author Simone Kühn of Ghent University and the Max Planck Institute for Human Development said, "This result shows that emotional self-control involves a quite different brain system from simply being told how to respond emotionally.”

When participants decided for themselves to inhibit negative emotions, the scientists found activation in the dorso-medial prefrontal area of the brain. This brain area is also activated when deciding to inhibit physical movement. On the flip side, when participants were instructed by the researchers to inhibit the emotion, a different, more lateral area of the brain was activated. Dr. Kühn concluded:

"We think controlling one's emotions and controlling one's behavior involve overlapping mechanisms. We should distinguish between voluntary and instructed control of emotions, in the same way as we can distinguish between making up our own mind about what do, versus following instructions."

The ability to manage one's own emotions plays a role in a wide range of mental health conditions. Traditionally, most studies of emotional processing in the brain assume that people passively receive emotional stimuli, and automatically feel an emotional response. This new research has identified a brain area that allows individuals to rise above having a negative emotional response and opens up interesting possibilities for future research.

There is an important caveat regarding these findings. Obviously, it's a thin line between remaining empathetic to the emotional distress you observe in others and allowing negative emotions to overwhelm you in a way that is counterproductive and debilitating. For example, in people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the brain becomes hypersensitive to fearful stimuli that vaguely represent the initial trauma.

2. Your Brain Can Be Trained to Self-Regulate Negative Emotions

Another new study, by researchers at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (BGU), used a simple computer-training task that changes the brain's wiring to regulate emotional reactions. This research dovetails with the findings of Dr. Kühn and her colleagues from 2013.

The January 2016 study, “Using Executive Control Training to Suppress Amygdala Reactivity to Aversive Information,” was published in the journal NeuroImage.

For this study, the researchers used fMRI to monitor the brain activity of 26 healthy volunteers before and after multiple computerized training sessions. Using executive control training, which is a form of mindfulness, participants practiced identifying whether a target arrow points to the right or to the left while ignoring the direction of arrows on either side of it.

The researchers also conducted a resting-state fMRI scan to assess brain connectivity during “no specific task” and later during an emotional reactivity task in which they were instructed to ignore negative pictures while in an fMRI brain scanner. A previous study by these researchers identified that computerized training sessions can reduce the tendency to ruminate in a repetitive-thinking cycle about a negative life event.

In a press release, Dr. Noga Cohen, who collaborated with Dr. Hadas Okon-Singer from the University of Haifa and the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Germany, said:

"As expected, participants who completed the more intense version of the training (but not the other participants) showed reduced activation in their amygdala—a brain region involved in negative emotions, including sadness and anxiety. In addition, the intense training resulted in increased connectivity between participants' amygdala and a region in the frontal cortex shown to be involved in emotion regulation.

These findings are the first to demonstrate that non-emotional training that improves the ability to ignore irrelevant information can result in reduced brain reactions to emotional events and alter brain connections. These changes were accompanied by strengthened neural connections between brain regions involved in inhibiting emotional reactions.”

Moving forward, the researchers plan to examine the impact of this non-emotional training on individuals who are depressed or anxious. The findings of this research may also be helpful for people who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or are at risk of developing high blood pressure reactions to negative emotional overload.

Cohen concluded, "It is our hope that the current work would lead to further testing and potentially the development of effective intervention for individuals suffering from maladaptive emotional behavior. While acknowledging the limitations of this study, which was based on a relatively small number of healthy participants and focused on short-term effects of the training, this may prove effective for individuals suffering from emotion dysregulation."

3. Your Orbitofrontal Cortex Can Predict Emotional Dysregulation

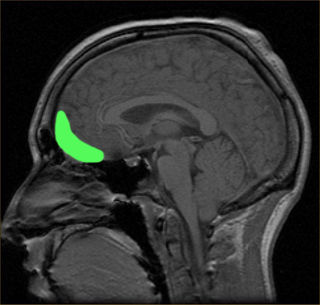

In the third study on the brain regions involved in emotional regulation, researchers at the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden found that people who have difficulty regulating emotions exhibited a decrease in the volume of orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) brain regions.

The July 2015 study, “Significant Gray Matter Changes in a Region of the Orbitofrontal Cortex in Healthy Participants Predicts Emotional Dysregulation,” was published in the journal Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience.

For this study, 87 healthy subjects were given a clinical questionnaire and asked to rate to what degree they have problems with regulating emotions in their daily lives. When the brains of the subjects were scanned using MRI, the neuroscientists found that the orbitofrontal cortex in the lower frontal lobe exhibited smaller volumes in the healthy individuals who reported that they have problems regulating emotions.

The greater the problem of emotional regulation, the smaller the volume detected. Decreased volume of the orbitofrontal cortex has also been observed in patients with borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder. Similar findings were also seen in other areas of the brain that are known for being important in emotional regulation.

In a press release, the first author of the study, Predrag Petrovic, M.D., Ph.D., who is a researcher at the Department of Clinical Neuroscience and Emotion Lab at Karolinska Institutet, said:

"The results support the idea that there is a continuum in our ability to regulate emotions, and if you are at the extreme end of the spectrum, you are likely to have problems with functioning in society and this leads to a psychiatric diagnosis. According to this idea, such disorders should not be seen as categorical, that you either have the condition or not. It should rather be seen as an extreme variant in the normal variability of the population."

In September 2015, I wrote a Psychology Today blog post, "Optimism and Anxiety Change the Structure of Your Brain," based on research from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign which found that adults who have a larger orbitofrontal cortex tend to have less anxiety and are more optimistic.

The researchers found that being optimistic is correlated with more gray matter volume in regions of the OFC. The scientists believe that the volume of the OFC is affected by a feedback loop that is driven by positive and negative emotions, although the specific correlation and causation require more research. The million-dollar question remains, "Does having a larger OFC make you more optimistic, or does being optimistic lead to a larger OFC?"

Conclusion: Your Brain Structure and Functional Connectivity Is Ever-Changing

Neuroplasticity guarantees that the architecture of your mind—and the functional connectivity of your brain—is never set in stone. Hopefully, these science-based findings will inspire you to be proactive about using mindfulness to consciously guide your thoughts away from hatred, negative emotions, and cynicism.

The latest neuroscience shows that mindfulness training can rewire your brain to gravitate towards loving-kindness, positive emotions, and empathy. The self-regulation of negative emotions and pragmatic optimism is in the locus of your executive control. Why not make a conscious decision to see the glass as half-full, starting right now?

© 2016 Christopher Bergland. All rights reserved.