Unconscious

Our Unconscious Mind Catches Grammatical Errors

The brain comprehends the syntax of language at an unconscious level.

Posted May 15, 2013

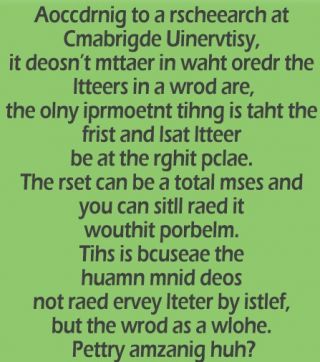

The paomnehal pweor of the hmuan mnid.

Typing on a keyboard is a perfect example of how our unconscious mind processes language and functions on autopilot. Are you someone who ‘hunts and pecks’ or do you type without looking at the keys? I had to take mandatory typing when I was in high school and was trained to type “the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog” (which holds all 26 letters of the alphabet) as quickly as possible without looking at the keys.

By typing without looking at the keys you learn implicitly where all the letters on a keyboard are located. To this day, I have no conscious awareness of where each letter is on the keyboard, but my fingers find them automatically. This is a universal phenomenon. If I asked you where the "J" and "F" are on your keyboard, would you know? However, I bet you can find them quickly without thinking much about it when you are typing or texting a sentence on autopilot.

In 2010, researchers at Vanderbilt University published a study titled “Fingers Detect Typos Even When Conscious Brain Doesn’t,” which confirmed this phenomenon. The skill of typing is managed by an autopilot system. When you type, you are able to catch errors even before they are picked up by your conscious brain.

"We all know we do some things on autopilot, from walking to doing familiar tasks like making coffee and, in this study, typing. What we don't know as scientists is how people are able to control their autopilots," Gordon Logan, Centennial Professor of Psychology and lead author of the study, said. "The remarkable thing we found is that these processes are disassociated. The hands know when the hands make an error, even when the mind does not."

Unconscious Mind Picks Up Grammatical Errors

Neuroscientists at the University of Oregon recently discovered that people detect grammatical errors with no conscious awareness of doing so. Their study titled “Grammar Errors? The Brain Detects Them Even When You Are Unaware” was published in the May 8, 2013 issue of the Journal of Neuroscience. In the study, subjects were flashed a series of experimental sentences—some were syntactically (grammatically) incorrect and others that were grammatically correct such as: "We drank Lisa's brandy by the fire in the lobby" vs. "We drank Lisa's by brandy the fire in the lobby."

While observing the sentences a 50 millisecond audio tone was played which distracted the participants enough to allow researchers to measure the conscious vs. unconscious awareness of grammatical errors. Researchers used electroencephalography and focused on a signal known as the Event-Related Potential (ERP) to measure brain activity.

Lead author Laura Batterink describes the method saying, "Participants had to respond to the tone as quickly as they could, indicating if its pitch was low, medium or high." Adding, "The grammatical violations were fully visible to participants, but because they had to complete this extra task, they were often not consciously aware of the violations. They would read the sentence and have to indicate if it was correct or incorrect. If the tone was played immediately before the grammatical violation, they were more likely to say the sentence was correct even it wasn't."

Helen J. Neville, co-author of the study said, “The key to conscious awareness is based on whether or not a person can declare an error, and the tones disrupted participants' ability to declare the errors. But, even when the participants did not notice these errors, their brains responded to them. These undetected errors also delayed participants' reaction times to the tones."

The brain processes syntactic information implicitly, in the absence of awareness. The authors observed that, "While other aspects of language, such as semantics and phonology, can also be processed implicitly, the present data represent the first direct evidence that implicit mechanisms also play a role in the processing of syntax, the core computational component of language."

Two-Year-Olds Can Understand Complex Grammar

This new research from the University of Oregon confirms findings of previous studies. In 2010, researchers at the University of Liverpool’s Child Language Study Centre found that children as young as two-years-old could decipher sentences containing made-up verbs, such as 'the rabbit is glorping the duck.' When asked to match the sentence with a cartoon picture, even a two-year-old could identify the correct image with the correct sentence.

The Liverpool study suggested that infants know more about language structure than they are able to articulate, and at a much earlier age than previously thought. Children may use the structure of sentences to understand new words, which may help explain the speed at which infants acquire speech. Dr. Caroline Rowland from the Institute of Psychology, Health and Society said: "When acquiring a language, children must learn not only the meaning of words but also how to combine words to convey meaning. Most two year olds rarely combine more than two words together. They may say 'more juice' or 'no hat', but don't know how to form full sentences yet."

Studies suggest that young children build their understanding of grammar gradually by observing and listening to people. Understanding syntax may be more of an implicit than explicit brain function. Even at 21 months – when infants can’t yet articulate words properly – they are already sensitive to the different meanings created by particular grammatical constructions. It appears that the brain’s ability to pick up grammatical errors at an implicit level begins at a very young age.

Rowland says, "Our work suggests that the words that children say aren't necessarily the extent of what they actually know about language and grammar.” Adding, “The beginnings of grammar acquisition start much earlier than previously thought, but more importantly it demonstrates that children can use grammar to help them work out the meaning of new words, particularly those that don't correspond to concrete objects such as 'know' and 'love'. Children can use the grammar of a sentence to narrow down possible meanings, making it much easier for them to learn."

Conclusion: Implicit Learning Also Applies to Second Languages

Scientists continue to fine tune differences between how our brain processes implicit and explicit information. This week researchers in the UK also discovered that the cerebellum has evolved to play a key role in human intelligence and cognition. It may be time to consider new teaching strategies for language acquisition and how adults are taught a second language.

Helen J. Neville from the University of Oregon concludes, “Children often pick up grammar rules implicitly through routine daily interactions with parents or peers, simply hearing and processing new words and their usage before any formal instruction."

She likens this type of learning to "Jabberwocky," the nonsensical poem from "Through the Looking Glass" by Lewis Carrol. In the story, Alice discovers a book that appears to be written in an unrecognizable language but later realizes that it was written inversely and is readable in a mirror. In terms of mastering a second language, Neville recommends to "Teach grammatical rules implicitly, without any semantics at all, like with jabberwocky. Get them to listen to jabberwocky, like a child does."