Spirituality

Why We Need to Raise Spiritual Children Now More Than Ever

The sense of urgency to tackle spirituality stems from recent events.

Posted April 15, 2019

For many people spirituality is a taboo topic; an irony since the majority of Americans believe in God, experience frequent feelings of spiritual peace and wellbeing, and the number of peer-reviewed publication titles on religion, spirituality, and health research has reached almost 8,000 annually.

The sense of urgency to tackle this sensitive issue stems from recent events; especially the evil perpetrated by neo-Nazi and white supremacists in Charlottesville, the mass school shootings at Parkland, and Santa Fe, the killing of Jews and Muslims in Pittsburgh and New Zealand.

I believe that now more than ever we should have a discussion about raising spiritual children. Now more than ever we need these spiritual children to grow up into spiritual adults. We need to raise spiritual children who have a sense of peacefulness, curiosity, industry, and awe, as well as a deep sense of empathy with others’ suffering. Children who grow up into adults who are resilient, optimistic, have a sense of belonging and feel connected to others.

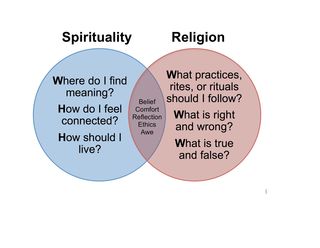

Are Religion and Spirituality the Same?

It is important to point out some similarities and differences between the concepts of religion and spirituality because many people think they are the same. The University of Minnesota's “Taking Charge of Your Health and Wellbeing” webpage points out:

Note: For a more in-depth discussion on the definition of Spirituality and Religion please see Doug Oman’s Chapter titled: “Defining Religion and Spirituality” in The Handbook of The Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 2nd Ed.

Research on Children and Spirituality

In his book titled The Spiritual Life of Children, Robert Coles interviewed hundreds of children from all walks of life and religious traditions including Christian, Islamic, Jewish, Hopi, and secular. “He reported what they had to say about how God speaks to them and how they listen and react.” He calls his method “documentary child psychiatry.” He first gets to know the child, then asks a significant question, then lets the child speak. Coles believes that children’s stories speak for themselves. Three examples of his work…

10-year-old Hopi girl:

…they [the Hopi children] gave me some memorable thoughts that crossed their minds, so memorable that now I recall those children when I find myself saying that I began then to have some fairly solid notions about the spiritual life of children.

Here, for example, is what I eventually heard (in 1975) from a ten-year-old Hopi girl I’d known for almost two years: “The sky watches us and listens to us. It talks to us, and it hopes we are ready to talk back. The sky is where the God of the Anglos lives, a teacher told us. She asked where our God lives. I said, ‘I don’t know.’ I was telling the truth! Our God is the sky and lives wherever the sky is. Our God is the sun and the moon, too; and our God is our [the Hopi] people if we remember to stay here [on consecrated land]. This is where we're supposed to be, and if we leave, we lose God.” (p.25)

10-year-old Carl:

And then Carl made a comment (asked a question, really) that had everyone nodding or smiling in agreement: “How can you know if God is happy, or if He isn’t happy if He’s sad?” (p. 32)

Betsy, when asked to draw a picture of God:

Most children who draw God’s face more than once, or that of Jesus, repeat more or less the same thing again and again - the same proportion to the features, the same use of colors, the same overall shape. Not Betsy. She once colored God’s face brown and told me that if she were black, as some of her classmates are, she’d want to draw God’s face that way “all of the time.” But a second thought took this expressive form: “I’d want to make Him white some of the time because He’s white as well as black. Don’t you think?” To that question, I answered yes. (p.46)

Spirituality, Teens, and Health

Dr. Lisa Miller reports that children who have an active, positive relationship to spirituality have:

- 40% less likely to use and abuse substances,

- 60% less likely to be depressed as teenagers,

- 80% less likely to have dangerous or unprotected sex and have positive markers for thriving including an increased sense of meaning and purpose, and high levels of academic success.

Other researchers found that:

- High school students who reported turning to spiritual beliefs when experiencing problems were less likely to use substances.

- Spiritual children and adolescents who are depressed have fewer thoughts of suicide and suicide attempts.

- Childhood overindulgence leads to diminished spirituality.

Connections Between Childhood Overindulgence, Materialism and Diminished Spirituality

One of the root causes of diminished spirituality is its connection to childhood overindulgence. A second factor is excessive materialism. The following studies demonstrate this.

In the first study we found that individuals who were overindulged as children were more likely to grow up:

- wanting the most money and owning the most expensive possessions,

- not interested in meaningful relationships,

- not interested in a meaningful life,

- not interested in making society better unless they got something out of it.

In a second study, we found that children who were overindulged grew up to be adults who:

- lacked self-control,

- were more materialistic,

- were unappreciative, ungrateful, and

- were less happy than those that were not overindulged.

In a third study, we found that adults who were overindulged as children:

- feel entitled to more of everything they deserve,

- were not interested in spiritual growth,

- have difficulties finding meaning in times of hardship, and

- are less apt to develop a personal relationship with a power greater than themselves.

Other researchers found that:

There is substantial evidence showing that people who are materialistic, consume more products and incur more debt have:

- lower quality interpersonal relationships

- act in more ecologically destructive ways

- have adverse work and educational motivation, and

- report lower personal and physical well-being

This is the second of three blog postings on the topic of spirituality. In my next posting, I will share “7 Strategies For Raising a Spiritual Child”.

Do all things with Love, Grace, and Gratitude

© 2019 David J. Bredehoft

References

Coles, R. (1990). The spiritual life of children. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Kasser, T. (2016). Materialistic values and goals. In Annual Review of Psychology. 67, 489-514. Abstract retrieved from https://www.annualreviews.org

Oman, D. (2013). Defining religion and spirituality. In R. F. Paloutzian & C. L. Park (Eds.), The handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality 2nd Ed. (pp. 23-47). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Debnam, K. J., Milam, A. J., Mullen, M. M., Lacey, K., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2017). The moderating role of spirituality in the association between stress and substance use among adolescents: Differences by gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 47(4), 818-828.

Svob, C., Reich, L., Wickramaratne, P., Warner, V., & Weissman, M. M. (2016). Religion and spirituality predict lower rates of suicide attempts and ideation in children and adolescents at risk for major depressive disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 55(10), 251.