Cognition

Subtle Ways Your Language Shapes the Way You Think

How language influences the person you become.

Posted September 29, 2020 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

You spend almost all of your waking hours—and even some of your non-waking hours—using language. Even when you’re not talking with other people, you’re still running a monologue in your head much of the time. And you also frequently use language when you dream. Given the degree to which you use language not only for communicating with others but also for thinking to yourself, it comes as no surprise that the language you speak shapes the kind of person you are.

In the first half of the twentieth century, psychologists tended to equate thought with speech turned inward. In other words, when you think, you’re just talking to yourself. As a result, they came to the conclusion that we can only think in terms that our language provides for us. This belief in linguistic determinism formed the premise for George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984, in which the government controlled people’s thoughts by limiting the words in the language.

In the second half of the twentieth century, psychologists argued that thought precedes speech, both in development and in real time. Thus, they argued that the structure of language is constrained by the limits of cognition, a position we could call cognitive determinism. For instance, the fact that all languages have the same basic underlying structure can be explained in terms of innate limitations in our memory and attention.

In the twenty-first century, we understand that the truth lies somewhere in between these two extremes. Now we recognize that sometimes language influences thought, and other times thought influences language. The goal of psycholinguists then is to determine in direction causality runs under particular circumstances.

In an article recently published in the journal Psychological Science, University of Edinburgh psychologists Alexander Martin and Jennifer Culbertson discuss a phenomenon known as suffixing preference. This phenomenon has been offered by a number of psychologists as a supposed demonstration of how innate cognitive limitations shape language.

In English and many other languages, you can modify the meaning of a word or change its grammatical role by adding a prefix before the root word, as in un-happy, or else by sticking on a suffix afterward, as in happi-ness. However, English, like most languages in the world, has a strong preference for suffixes over prefixes.

In other words, there are many more suffixes than prefixes in most languages, hence the term suffixing preference. In fact, a survey of nearly 1,000 languages found that 55% had a strong or moderate preference for suffixes, while only 15% had a strong or moderate preference for prefixes. The remaining 30% either used very few suffixes and prefixes or else used them in roughly equal numbers.

The standard explanation for the suffixing preference is a proposed cognitive bias that makes the beginnings of sequences more salient. This assumption is based on the results of studies that look at how people process series of stimuli.

For example, we have people listen to a sequence of musical notes, such as do-re-mi-do. They then hear two more series, fa-re-mi-do and do-re-mi-fa. Most people will judge the series with the change at the end as more similar to the original than the one with the change at the beginning. For some reason, a change at the beginning just sticks out more than a change at the end.

However, Martin and Culbertson indicate that all studies of the suffixing preference have been conducted in countries that are WEIRD—Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic. Much of the WEIRD World speaks English, and the rest speak other European languages that are closely related. Also, as it turns out, all European languages have a strong suffixing preference. This means we can’t rule out the possibility that this phenomenon is due to experience with the language rather than to an innate cognitive bias.

What’s needed is a test of the suffixing preference in a non-WEIRD country where the language has a strong prefixing preference. This is exactly what Martin and Culbertson did.

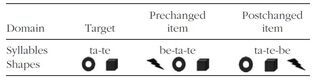

The design of their experiment was simple. Half of the participants listened to a series of syllables, such as ta-te, followed by two additional series, such as be-ta-te and ta-te-be. They were then asked to choose which one was more like the original. The other participants viewed a series of shapes, such as those in the picture below, again choosing the subsequent series that more resembled the first.

The researchers first performed the experiment on native English speakers recruited throughout the WEIRD World over the internet. The results were consistent with previous research, in that the participants preferred sequences with the change at the end rather than at the beginning, whether the stimuli were syllables or shapes.

Next, the researchers left the WEIRD World and traveled to rural Kenya. This time, the participants in the experiment were native speakers of a language called Kiitharaka, which uses many prefixes but few suffixes. If the suffixing preference is an innate cognitive bias, then the Kiitharaka speakers should also prefer the sequences with the change at the end rather than at the beginning.

But this isn’t what Martin and Culbertson found. Instead, the Kiitharaka speakers deemed the sequences with the change at the beginning to be more similar to the original. Thus, the results suggest instead that the way we process sequences—including those of meaningless sounds and visual symbols—is influenced by the structure of our language, rather than by a cognitive bias, as proposed by WEIRD psychologists.

Of course, this experiment needs to be replicated in a number of non-WEIRD cultures. This, however, can be difficult and expensive for WEIRD-World psychologists to carry out. Nevertheless, this study does serve as a reminder that findings in the WEIRD World don’t necessarily extend to the rest of humanity.

References

Martin, A. & Culbertson, J. (2020). Revisiting the suffixing preference: Native-language affixation patterns influence perception of sequences. Psychological Science. Advance online publication. DOI: 10.1177/0956797620931108