Career

What Does Alienation Feel Like?

The psychological consequences of forever making things that don't belong to us.

Posted October 30, 2019

This post is nothing fancy or profound; I just want to put some emotive meat on Karl Marx’s useful, perhaps essential, yet always slightly skeletal, concept of alienation.

The necessity of working for someone else, experienced by all but a few, carries the implication that what one makes, or the value of what one does, won’t ever belong to them. It would be surprising if spending so much time on the clock, all in order to hand over what’s been done at the end of the day, didn’t have some sort of psychological consequences.

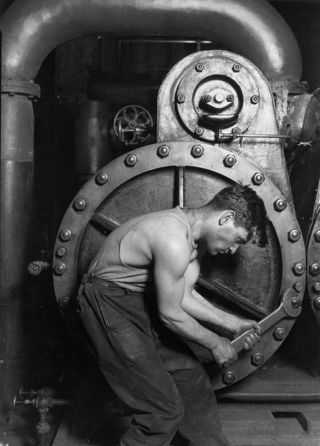

There’s no better place to start than Marx’s most basic formulation: “the worker is related to the product of labor as to an alien object.” When a child makes something — whether it’s a sculpture or a snow fort — what they’ve made belongs to them and them alone. Indeed, if another child or a malicious adult destroys their fort, the kid who built it experiences its destruction as an attack on their person. However, when hours of work go into something that doesn’t have anything to do with the hands that made it, the object stands apart. It can take on a disturbing aspect: The worker’s time, energy, and body have been externalized in a thing they do not own; from a certain point of view, it owns them.

+++

Although sociologists and psychoanalysts, feminists and cultural critics, and many others have all put Marx’s idea to work, its influence hasn’t been as deep in psychology proper. It’s a shame because it’s obvious that our work is one of the most important determinants of how we feel — whether positively or negatively. Whatever one thinks about communism, the fact that people don’t own what they produce remains. We can certainly, as psychologists or students of psychology, think about how working in these conditions, just about every day, affects our mental well-being.

There is one moderately famous paper from the 1950s by Melvin Seeman, called “On the Meaning of Alienation.” In it, the UCLA social psychologist tried to formulate alienation in the psychological terms of the day. I’m going to follow him through four of the five aspects of alienation he analyzes (though not at all that closely).

1. Powerlessness. When a person has no control over the things they make, they don’t have any power over what’s done with them. Someone who works at a factory that cans beans might see all sorts of hungry people around them, and feel the urge to help, but their ability to help doesn’t extend to giving out the cans they produced that day. Despite being around food all day, they have no food to give.

It goes further: The solid eight hours spent at work means that our imagined canner can’t have produced anything of their own during that time (and if they did, it would be considered ‘stealing’). All of the energy that was spent on someone else’s stuff is energy that can’t be spent on oneself.

2. Meaninglessness. When someone knows they won’t have any power over what they’re making, the act of working they’re engaged in loses the meaning it sometimes has. If you think of the things that you’ve made because you wanted to, you’ll probably be able to appreciate Marx’s line that runs “man produces even when he is free from physical need and only truly produces in freedom therefrom.” When you made that piece of jewelry for someone, or painted that painting, both the process through which you made the thing, and the thing itself, are meaningful precisely because you didn’t have to do them.

Once your labor no longer belongs to you, you aren’t able to make the choices that invest the process of working with meaning. For too many, the daily grind doesn’t mean anything — except insofar as it means nothing else can be done instead.

3. Isolation. Part of getting used to working for a wage is coming to see oneself as a ‘worker.’ Different people have different reactions to this designation; some are proud of their ‘work ethic,’ others try to reject this self-conception and ‘work for the weekend.’ Whatever the appraisal of one’s employment situation, the idea that ‘I am a worker’ comes to apply to other people as well. As Marx puts it, “each man views the other in accordance with the standard and the relationship in which he finds himself as a worker.”

Coming to see other people as, at bottom, workers means that they also must be powerless to create anything meaningful. They’re also cut off from the activities that make someone an individual (both in feeling and in actuality) — and therefore, so much less interesting than one.

Of course, we all know there are much more mundane ways that our jobs isolate us. We’re always there, and if we’re off, our friends probably aren’t. Often, the people we see the most are our ‘co-workers,’ those we have no choice but to see.

4. Self-Estrangement. What happens when a human being is powerless, cannot find meaning in what she does, and is isolated from other human beings?

For Marx, the answer was clear: People become alienated from themselves.

Each of the three aspects of alienation we’ve looked at so far corresponds to a part of human life we generally think as essential. And so our own ‘self’ becomes strange, alien: This is not what I’m supposed to be doing, this is not who I’m supposed to be. But the economic pressures which force us into this state of mind are the same that make it impossible to escape from it.

+++

This post barely touches the myriad issues inherent to alienation, nor the many important issues related to it, like false-consciousness, commodity fetishism, and what a non-alienating society would look like. Hopefully, though, there are a few people who’ll understand an argument about, or just a passing reference to, alienation a little bit better.

References

Marx, Karl (1959). Economic & Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, Progress Publishers: Moscow. url: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/manuscripts/preface.htm

Seeman, Melvin (1959). "On the Meaning of Alienation," American Sociological Review 24:6. url: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2088565?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents