Beauty

Adolescence and the Desire for Physical Beauty

Physical looks can matter more to the adolescent than the child.

Posted February 4, 2019

First consider the possible function of physical human beauty.

Suppose it is some constellation of characteristics that can arouse attraction in the beholder to the beheld. The display can have an evolutionary power this way, drawing people to their sense of personal beauty in the other, getting them socially and sexually together to enjoy physical intimacy and perhaps to create the next generation of human life.

What constitutes human beauty may also be culturally influenced by fashion—the nomination of physical characteristics widely appreciated and generally upheld as most to be prized, celebrated in popular media this way.

Now consider how these popular standards of physical beauty might impact growing adolescents.

It’s not a question that a child spends much time considering; but it is definitely one that painfully preoccupies young adolescents, particularly after puberty has begun: “How do I look?”

Now time spent seeking the mirror for answers and examining one's reflection in critical detail absorbs increasing amounts of time.

At this age, physical self-consciousness can become acute as hormones change the body beyond one’s control, as skin texture and body shape alter in ways one must learn to live with, like them or not. Acne, for a painful example, can afflict the face, making facing one's social world with confidence harder to do. And now the concealing power of cosmetics to mask passing blemishes (from everyone but oneself) can be resorted to.

Because the onset of puberty often coincides with the age of social cruelty (the middle school years), developmentally insecure young people can aggress against each other to secure standing and place among peers. Now physical feature can come under teasing attack: “They call me Mophead!'", "They call me Zits'!" So in counseling, I try to encourage not taking these experiences the wrong way. I suggest how this treatment isn't about anything wrong with them: it's about other people wanting to act mean. In addition, such name-calling is mostly self-revealing. Students usually tease another about what they fear being teased about themselves. Although appearing to be offensive, such teasing is really a defensive act.

And now the unwritten but generally understood rules for physical deportment and display begin to take hold -- adolescents no longer willing to appear childlike, while gender differences become more visually pronounced, boys striving to to be seen as more manly and girls as more womanly.

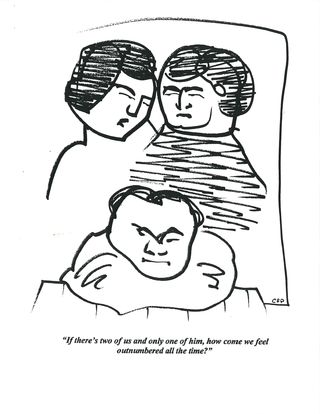

Thus begins young people working overtime to look good, putting in endless hours bravely confronting their reflection in the mirror. All the while the Beauty Industry is hard at work crafting idealized images for them to strive for and imitate to the degree they can. In most cases they conclude: “I’ll never look that good!" And wonder: "What’s the matter with me?”

A consortium of Fashion, Fitness, Cosmetics, Diet, Nutrition, Health, Recreational, Advertising, and Entertainment interests constantly parade beautiful young icons and models before admiring eyes, representing how one can (and should?) physically look at best. These portrayals are very hard for insecure youth not to identify with, internalize, strive to imitate, mostly fail to do so and end up feeling physically deficient in some painful way. “What can I do about my hair?” Posters of popular idols on teenage walls can both inspire and discourage.

Negative body image concerns can be acquired at this impressionable age – at worst, causing critical comparisons, body shaming, and self-loathing: “I hate how I look!” When the appearance I have is allowed to define the value of the person I am, destructive self-management can take hold. Maybe the girl crash diets and takes laxatives to appear “thin enough” or the boy takes supplements for muscle building to appear “strong enough.” Or maybe either sex gets into compulsive starving, purging, over-exercising, or some combination of the dangerous three.

Where might young people see such popular, idealized images in actual life? There are many online and offline places, but consider a spectator example close at home -- the high school football game. Here, on the socially competitive field of play, before an enthusiastic crowd, tough young men, maybe looking like action figures, bulk up in padding to aggressively play a collision sport, while on the sidelines pretty young women, maybe looking like shapely models, are trimly attired in brief, tightly fitting costumes to cheer them on. What a powerful pageant of physical ideals!

Appearance socially matters. It is one part of conforming to belong, fitting in, and measuring up, all factors that influence a young person’s social approval and standing. They believe as the Poet said that “all the world’s a stage,” spending much time preparing themselves in private before going out in public to brave whatever audience response awaits them. They disbelieve that old saying, "don't judge a book but its cover," because they know their physical; "cover" socially counts for so much.

By high school, the importance of physical appearance is set. For both sexes, physical attractiveness is measured by the degree to which one approximates the culturally dominant standards of facial and bodily beauty. An attractive physical appearance can be a passport to social acceptance and inclusion: the better you look, the better you are often socially evaluated and treated. And this preferment is not just by peers but by adults as well, which is partly why young people have some social cause to want to look as good as they can.

For those interested in what academic psychology has to say about the social power of physical beauty (see Psychological Bulletin, Vo 126(3), May 2000, 390-423, Judith H. Langlois et al) there is support for this idea. “Attractiveness influences development and interaction. In 11 meta-analyses…a) raters agree about who is and is not attractive, both within and across cultures; b) attractive children and adults are judged more positively than unattractive children and adults, even by those who know them; c) attractive children and adults are treated more positively than unattractive children and adults, even by those who know them; d) attractive children and adults exhibit more positive behaviors and traits than unattractive children and adults.”

Apparently, perceived physical beauty can be used as a social discriminator – it can affect how a person is valued and treated – ‘better’ when meeting these standards, and ‘less well’ when one does not.

Then there can be risks at the extremes. The very beautiful can attract unwanted attention, while the very un-beautiful may have a hard time getting the attention they want. For example, the very beautiful new 8th grade girl may upset the existing pecking order of dominant, popular girls and become the target of their envious rumor and gossip to keep her competition down and out. “She had a really bad reputation in her last school!” As for the ungainly, physically awkward new 8th grade boy, he may be socially ignored by guys who avoid befriending him lest they risk becoming socially known by the unattractive company they keep. “Who wants to hang out with a loser?”

How might parents respond to their adolescent’s concern with personal attractiveness? One parent wrote me about how she answered her daughter’s appearance question at a very significant time.

“How do I look, how do I, tell me?” the daughter asked, dressed up for her first school dance.

The mom enthusiastically replied: “You look like you’re ready to have a dancing good time!”

And with “a swish of her skirt,” the girl eagerly raced out the door to catch her ride.

Instead of fixating on appearance, the mom positively focused on attitude, enjoyment, and activity.

However popularly and culturally defined, physical beauty can be a complicated characteristic to manage. Even when it advantages an adolescent’s life, maintaining such an extremely compelling appearance, socially and emotionally depending on it to feel okay, beauty can be a hard concern to bear: “I constantly worry that I don’t look my best!”

In the extreme might be this statement of anxiety: "I hate seeing myself in the mirror if my face is starting to look fat!" Maintaining and trading on an extremely comely appearance can be burdensome. By comparison, those who accept being less beautifully endowed may feel relatively free from this oppressive preoccupation: "Regular looks are fine with me. Besides, I know they are not all I am."

In closing, I would like to quote French artist, Jean Dubuffet’s observation about physical beauty since his words are still meaningful to me now.

“I believe beauty is nowhere. I consider this notion of beauty as completely false. I refuse absolutely to assent to this idea that there are ugly persons and ugly objects. This idea is for me stifling and revolting…This idea of beauty is however one of the things our culture prizes most…I find this idea of beauty a meager and not very ingenious invention, and especially not very encouraging for (humanity.) It is distressing to think of people deprived of beauty because they have not a straight nose, are too corpulent, or too old… (Culture) will not suffer a great loss if (it) loses this idea. On the contrary, if (people) become aware that there is no ugly object or ugly person in this world, and that any object of the world is able to become for anyone a way of fascination and illumination, (they) will have made a good catch.” (Jean Dubuffet, works writings, and interviews, 2006, Ediciones Poligrafa, Barcelona.)

For many adolescents, growing up in a culture that exalts it, physical beauty can often prove to be a pretty unattractive concept.

Next week’s entry: Talking about Failure with Your Adolescent