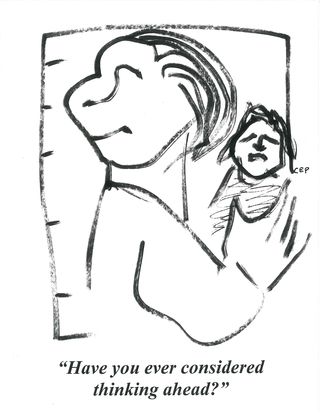

Deception

Confronting Adolescent Lying and What Parents Might Say

Parents can acknowledge the purposes of teenage lying and then discuss the costs

Posted October 15, 2018

Simply put, at best what parents can expect from their adolescent is this: "Keep your word to us and tell us the truth."

The last blog dealt with broken promises. This blog deals with confronting adolescent lies.

Consider two great awakenings to personal power in relationship to parents that usually come when the child enters adolescence, around ages 9 – 13.

THE TWO AWAKENINGS

First is understanding that a parent cannot make them or stop them without the young person’s consent. “My parents are not in command of me anymore. They have to convince me to cooperate. My choices are up to me!” Now parents find the adolescent becoming more actively resistant with argument and passively resistant with delay.

And second is awareness that parents have become increasingly ignorant of what is happening in her or his inner and outer life. As their primary informant about what is going on, the teenager understands: “Most of what they know about me is what I choose to tell!” Now parents can find personal information more selectively and unreliably shared.

THE NATURE OF LYING

There is lying by omission: what she or he chooses not to tell. And there is lying by commission: fabricating what is told. In early adolescence, most young people will experiment with both forms of dishonesty.

All lying is to a purpose: for example, to get what is wanted, to get out of what is not wanted, or to get away with the forbidden. In all these ways and others, it is an effort to get freedom for or freedom from, at a more freedom loving age. So during Early Adolescence parents are likely to see an increase in this behavior and to catch the young person at doing it. Generally, first time caught lying to parents is not the first time a lie has been told. She or he has probably taken advantage of their ignorance this way before.

When a lie is caught, parents should treat it seriously. They can share how it feels to be lied to. “We feel hurt and angry when you don’t tell us the truth!” They can take a value stand against dishonesty, “We believe lying violates your responsibility to keep us adequately and accurately informed, the same responsibility we have to be honest with you.” They can apply some symbolic consequence to work off the offense, “You’ll need to do an extra chore this weekend before doing anything you want to do.” And (hardest of all) they must reinstate their expectation for honest communication. "We expect you to tell us the truth." Most important, parents can take this opportunity to have a conversation about both the temptations and costs of lying.

When parents will openly talk about why lies are told, how they both serve and harm the liar; that they know so much can provide some disincentive for doing it. Particularly important in this discussion is including an appreciation of the courage it can sometimes take to tell them a hard truth. "Thank you for being brave enough to share what you didn't want to tell and what we didn't want to hear."

So, consider some temptations to lie that parents might mention.

TEMPTATIONS TO LIE

Lying to keep people from the truth. "I wasn't involved."

Lying to fool people into believing what isn't so. "I have my parents' permission."

Lying to deny wrongdoing. “I didn’t do it.”

· Lying to exaggerate: “All my friends’ parents are okay with this.”

· Lying to get one’s way. “From now on I’ll remember, so you can let me go!”

· Lying to mislead parents. “At an overnight, I won’t be out after dark.”

· Lying to misinterpret. “I’m just run down from not getting enough sleep.”

· Lying to cover up. “My friends will tell you I wasn’t there.”

· Lying to pretend understanding. “I know all about it; so don’t worry.”

· Lying to create a false impression. “It’s not my fault for looking older!”

· Lying to discredit accusers. “She only said that because she’s jealous.”

· Lying to make a false claim.“This was the first time I ever tried it.”

· Lying to tell what parents want to hear. “I’ve been studying the whole time.”

· Lying to avoid disappointing parents. “I would never let you down.”

· Lying with false promises.“I swear I’ll never do that again!”

· Lying to believe what isn’t so. “It’s not a problem; I can quit any time.”

· Lying to deny that actions are doing harm. “This isn’t hurting anyone.”

· Lying to get out of being blamed.“How was I to know?”

· Lying to shift responsibility. “They made me do it.”

Lying to defame others:"They treat me unfairly."

· Lying to lie about lying. “I wouldn’t lie to you, my own parents!”

· Lying to flatter. “I wouldn’t admit this to anyone but you.”

· Lying to lie about a lie.“What I said didn’t mean what you thought.”

· Lying to pretend reform. “I learned my lesson.”

· Lying to excuse.“I didn’t mean to; it was an accident.”

· Lying to shape what others think.“This is how it really was.”

There’s no point in saying that lying isn’t serviceable; because it is. If it wasn’t, people wouldn’t do it so often. But there is a point in saying that no matter how serviceable lying may seem at the time, it always comes with significant costs. Ask your teenager to consider a few examples of what these might be.

COSTS OF LYING

· Lying loses trust. “Now it's harder to believe what you say.”

· Lying has harmful impact. “We feel betrayed when you mislead us.”

· Lying complicates life. “I have to remember what I did and said I did.”

· Lying creates distance. “I don’t want my parents getting too close.”

· Lying reduces availability of parental help: “They haven’t a clue about what’s really going on.”

· Lying increases loneliness. “Other people don’t really know about my life”

· Lying encourages more lying. “I have to lie to cover up the lies I’ve told.”

· Lying is frightening. “I’m scared of being found out.”

· Lying confuses thinking. “I can’t see the truth for the lies I’ve told.”

· Lying becomes habit forming. “The more I lie, the more I lie again.”

· Lying fools the liar. “I’m starting to believe some of the lies I’ve told.”

· Lying loses credibility. “People don’t believe me anymore.”

· Lying demands secrecy. “I need to conceal truth from others.”

· Lying gets double punished. “You did wrong and then you lied about it!”

· Lying feels out of control. “It just gets harder to keep my stories straight.”

· Lying is self-incriminating. “Every lie is just more evidence against me.”

· Lying takes extra effort. “It takes more work to lead a double life.”

· Lying slows parental decision-making down. “We need extra time to check out what you say.”

· Lying lowers self-esteem.“I don't feel able to tell the truth.”

· Lying abuses the liar. “Lie to others and I treat myself as a liar.”

· Lying is hardest on the liar. “We’d rather be the people lied to than the person reduced to telling lies.”

WHAT PARENTS MIGHT ALSO EXPLAIN

In addition to itemizing some temptations and costs of lying, parents might explain this. What the adolescent may fail to understand is that she or he is just an adult-in-training. Now is later. How they practice communication now is how they are likely to practice it in other and future relationships. Youthful habits of communication can be long-lasting.

Thus, a teenager who has gotten into persistent lying with parents (perhaps to conceal illicit or unhealthy activity) may continue to lie in significant relationships to come. And although parental devotion may withstand these falsehoods, a romantic relationship may break as the loved one simply walks away. “I don’t want to be with someone who lies to me!”

As for lying about someone, the liar inflicts double injury to that person: First is anger at being lied about, and second is anger at those who are taken in by or want to believe the lie -- anger at believers who are damaging one's reputation. "We hear she only does so well because she cheats on tests."

Parents can finally explain how in lasting relationships of the caring kind,

· You can’t have trust without truth;

· You can’t have safety without sincerity;

· You can’t have intimacy without honesty;

· You can’t have commitment without candor.

Of course, quality of communication that parents model can make an influential difference. Most of what parents give their adolescent is by example – by how they act and are by character defined. Thus, when a family leader models lying for the children, whether that adult is doing so at home or out in the world, then lying is what some of these impressionable young people may feel encouraged to imitate and follow. “From watching my parent, I learned to say whatever I can get away with at the time.” So: for your kid’s sake, don’t lie. Tell the truth. It can be hard to do, but in the long run it can turn out harder for your adolescent when you don’t.

And when it comes to managing personal relationships that matter, consider giving your teenager this advice. “Do not get socially or romantically involved with anyone who regularly lies because you may get seriously hurt. If you see them continually lie to others you can expect that sooner or later they will lie to and maybe about you.”

Next week’s entry: When Parents Pay Money for Adolescent Cooperation