Memory

Perceived Control and Coping With Threats We Want to Forget

Willful ignorance and perceived control.

Posted August 9, 2023 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- We might sometimes be tempted to ignore information that can cause negative emotions.

- This is especially the case when we feel like we don't have much control over the outcome of the information.

- Individuals can shield themselves from these feelings by selectively forgetting distressing information.

- Enhancing people’s perceived control reduces the need to forget distressing information.

Willful ignorance: A self-preservation mechanism

We are routinely exposed to vast information, some of which can be pretty distressing. For instance, most of us don’t particularly enjoy learning about a looming economic recession or hearing reports of a violent conflict in our vicinity. Because such information can bring on unpleasant feelings like anxiety or fear, we may consciously choose to overlook it. This phenomenon is commonly referred to as willful ignorance. However, such behavior can be detrimental in the long term, as it prevents us from accessing valuable insights that could enhance our decision-making.

Low perceived control and willful ignorance

Willful ignorance is more prominent in settings where individuals have limited to no control over how events unfold. For example, people tend to avoid information about aspects of themselves that are usually perceived as inborn traits such as genetic predisposition to incurable diseases, IQ, and beauty. Nevertheless, in numerous circumstances, there are actions individuals can take to transform unfavorable results into less undesirable ones. If people have limited awareness in this regard, they might consequently choose to close their eyes to potential problems instead of facing them. For example, many illnesses can be managed better or their effects reduced if we catch them early. Yet, we often hesitate to take medical tests that could help us stay healthy or even save our lives.

Perceived control and selective memory

One way people can engage in willful ignorance is by forgetting unpleasant information or remembering it in a more positive light. We are more likely to remember our successes rather than our failures, good things rather than bad things, and occasions in which we behaved morally rather than when we did not.

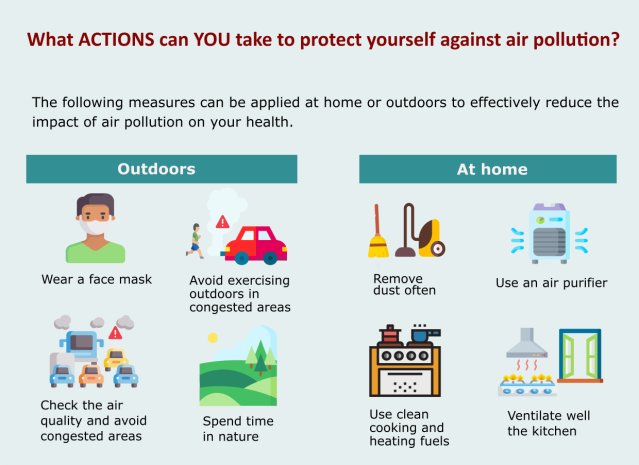

In one of our studies, my co-authors and I tested whether an increase in perceived control can enhance memory retention of distressing information. We surveyed about 1200 participants from across India and split them into two groups: One group was provided with a list of simple but effective measures they could use to protect themselves against air pollution, while the other group was not provided with this list. The purpose of this list was to increase participants’ perceived control over the detrimental effects that air pollution can have on their health. We then exposed participants from both groups to threatening information by telling them how many years of life expectancy people living in the same geographic area lose on average because of air pollution. Finally, we tested whether they could recall this information shortly after receiving it.

We found that participants who were provided with the list of protective measures were about 25 percent less likely to forget the distressing information than their counterparts who were not provided with that list. Interestingly, we also found that increasing perceived control works best for those participants who were underestimating the risks before being exposed to information. Our findings suggest that willful ignorance is especially widespread among individuals that are probably the least prepared for the risks. Importantly, increasing perceived control appears to help them the most in acknowledging the threats.

What do we learn from this?

In our daily lives, many of us occasionally encounter situations over which we feel we have very little control. For instance, the outbreak of COVID-19 has demonstrated how a lack of perceived control over infectious diseases can result in fear, uncertainty, and challenges in implementing effective public health measures. Likewise, the pressing concern of climate change is notorious for often being disregarded, as individuals and communities might feel helpless before the wide impacts of environmental deterioration and extreme weather events.

Our study provides some guidelines on how to reduce willful ignorance of important issues. One essential takeaway is that raising awareness alone is not sufficient to prompt people to engage with distressing information; they also need practical advice on how to cope with its implications.

References

Balietti, A., Budjan, A., Eymess, T., & Soldà, A. (2023). Strategic ignorance and perceived control. AWI discussion paper series no. 730.

Eil, D., & Rao, J. M. (2011). The good news-bad news effect: asymmetric processing of objective information about yourself. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 3(2), 114-138.

Mischel, W., Ebbesen, E. B., and Zeiss, A. M. (1976). Determinants of selective memory about the self. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 44(1):92.

Möbius, M. M., Niederle, M., Niehaus, P., & Rosenblat, T. S. (2022). Managing self-confidence: Theory and experimental evidence. Management Science, 68(11), 7793-7817.

Oster, E., Shoulson, I., & Dorsey, E. R. (2013). Optimal expectations and limited medical testing: Evidence from Huntington disease. American Economic Review, 103(2), 804-830.

Saucet, C., & Villeval, M. C. (2019). Motivated memory in dictator games. Games and economic Behavior, 117, 250-275.

Sedikides, C. and Green, J. D. (2009). Memory as a self-protective mechanism. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3(6):1055–1068.