Dreaming

You May Already Be Living the Life of Your Childhood Dreams

Personal Perspective: How my son showed me the value of unshackling our dreams.

Posted September 13, 2022 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- My 5-year-old's question about what he can be when grows up caused me to examine my own meandering path.

- The value of childhood dreams doesn't reside in their attainability, but in what they represent.

- While parents are tasked with raising children to exist and thrive in the "real" world, we should take care not to constrain what that could be.

- Adopting humility about the unrelenting serendipity of life can help us to aim for the stars without fear or regret, wherever they may be for us.

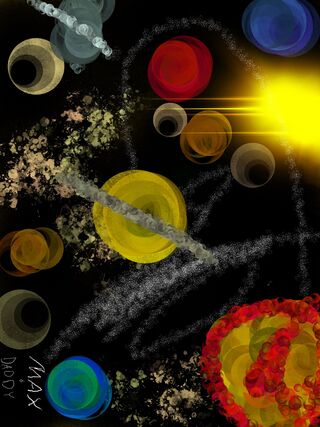

After poring over a book about the solar system, our 5-year-old informed us that when he grows up he’d like to be an astronomer, but also a drawing guy—he meant an artist—and a school guy (i.e. a teacher).

Making sense of it all

Our son makes a lot of offhand comments just as he’s supposed to be getting into bed. It’s often a procrastination technique, but this comment landed a little differently with me. He’s trying to understand how the world works, and the inputs to this complex equation are everything in his ever-expanding universe. This was a little boy trying to reconcile that week’s excitement about the planets and the moon, and the sun with the rest of his day spent coloring pictures in school.

I kissed the top of his head and told him I thought it was a great plan, but then he asked if he could really do that—be an astronomer, a teacher, and an artist—and I didn’t know what to say. There just aren’t many people who get paid to gaze at the stars and teach and draw. My wife jumped in to tell him that maybe he could teach astronomy to his future students.

“And you could draw for fun like Daddy does,” I added, referring to my hobby of drawing gag cartoons about psychiatry and life in general.

Our son was wholly unimpressed, especially the drawing like Daddy part.

“No, I think that every week I’ll work for three days as an astronomer, and one day as a drawing guy, and one day as a school guy.”

With the decision made, he was able to settle into bed, but his question stayed with me. Is 5 years old the right age to inject reality into his dreams? It couldn’t be, but when does a parent come to own the dour responsibility of stomping on a child’s perfectly harmless fantasies?

My own winding road

I thought back to my own meandering path. At age 5, I told my parents I wanted to be a doctor so I could work with my father in his office. I seem to remember them telling me I could be whatever I wanted to be if I worked hard enough, and they got me a Fisher-Price doctor kit. With this mantra engrained in my 1980s to 1990s upbringing, it’s become my natural stance whenever our son thinks about his own future.

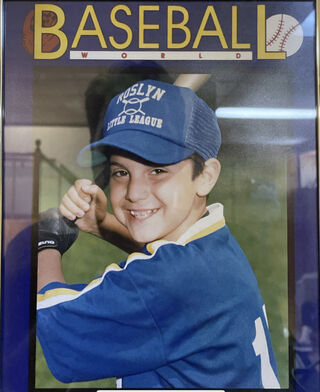

By age 8, I was going to be a baseball player, but this fantasy would not last even through middle school.

By high school, I was enjoying psychology classes and was writing for the paper, so I thought I’d be a psychologist or a columnist for a newspaper. In college, I watched movies on repeat and wanted to write screenplays that would become smash hits in Hollywood. Unfortunately, none of the stuff I wrote as a college kid in Providence gained any traction with agents in Los Angeles. The rejections scorched me to my core, and I did my best to reassure myself, okay, this is kind of like not getting to be a professional baseball player. It’s okay. What’s next? Then I decided to go to medical school and wrote an essay pronouncing that I had wanted to be a doctor since I was 5.

In those next four years, I kept writing but was more focused on short stories about medicine. I was struck by how rich the world of medicine was in interpersonal drama, character arcs, and pathos. The work of caring for real people inspired great stories and the experiences I had let me practice the art of perceiving people’s stories and reflecting back what I saw. It was a particularly useful skill to have cultivated when I decided to specialize in psychiatry, where much of the job seems to be dependent upon perceiving and reflecting. No field of medicine is so foundationally built upon people’s stories.

An insider's perspective on living with cancer

At age 33, a grown-up by anyone’s standard—especially by my son’s, who recently guessed that I was either 100 or 17 years old—I was dealt an unexpected blow in the form of kidney cancer. In an instant, I had gained the novel and unwelcome perspective of a seriously ill patient while remaining in full possession of my medical knowledge.

At the same time, I used writing to understand my own experience better. Whenever I felt like crying or screaming or even jumping for joy, I put those feelings into essays. I know from my work in psychiatry that putting thoughts and emotions onto the page help to process and integrate them into one’s own psyche. Only then can we move forward or even grow from them.

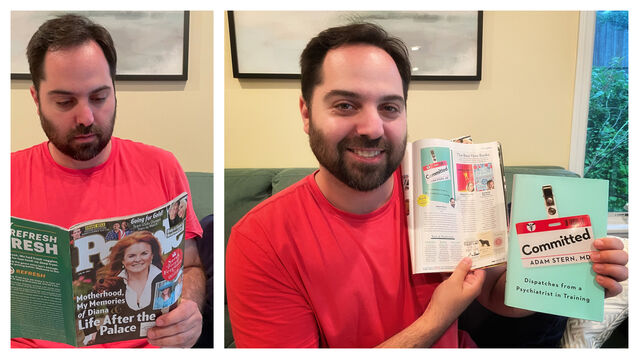

It was after reading a piece of mine online that a literary agent first approached me, and together we put together a book proposal about finding love and human connection over the course of my psychiatric training. That book by the sheer serendipity of the universe ended up being featured in People magazine, and now I’m working with a team in Hollywood to see if we can make a show out of it.

As I was about to leave my son’s room and turn off the light, I paused.

“You know, bud, I’m kind of like a doctor and a writer and a drawing guy so I think you really can do anything when you’re grown up.”

“I know,” he replied, suddenly sounding very tired. “Night night.”

“Okay. Night.”

Unable to be tamed, planned, or timed, childhood dreams are still worth embracing

Some dreams are ever so far out of reach no matter how much support we have, and life can be torturously unpredictable. But when I stop to remember all of the journey, so much of my life has turned out just the way I hoped. I think of my own parents’ encouragement with gratitude and know that not everyone has that message engrained within them. Wherever the line exists to mark the end of fantasy and the beginning of setting realistic expectations, I haven’t found it yet, and truly I hope I never do.