Dopamine

Why We Get Addicted

How our heatlhy drive to achieve and succeed can turn against us.

Posted December 21, 2020

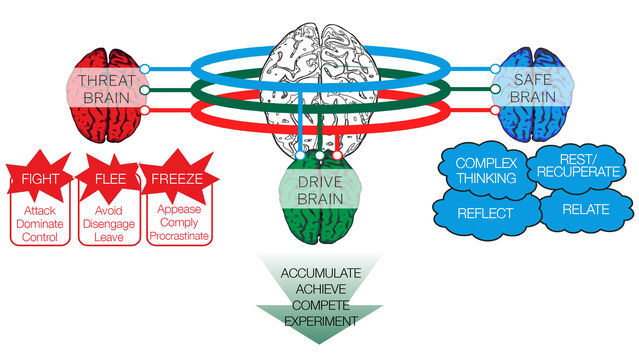

Emotions are sensations in our body that motivate us to act to achieve the basic goals of survival, accumulation and affiliation. Threat brain, our oldest emotion-motivation system enables us to recognise and respond to danger (survival). Drive brain motivates us to seek out pleasurable and rewarding experiences (accumulation). Safe brain motivates us to rest, recover and form relationships with others (affiliation). When all three motivation systems are working together we are less likely to get trapped in harmful "loops" of feeling, thinking and behaving.

Unfortunately, many of us do get caught in unhelpful habits that are sustained because these motivation systems are dysregulated and out of balance. One consequence of dysregulation is the experience of toxic drive which can lead to addiction, ill health and can interfere with our ability to sustain healthy relationships.

In a regulated, non-toxic state our drive brain motivation system is a great asset. It is responsible for fuelling the energetic, progressive, inventive aspects of our personality and, at its best, it enables us to participate fully in life and to experience the rich varieties and challenges of the world in a positive way.

Our drive brain is activated by our sympathetic nervous system and powered by the potency of the neurotransmitter dopamine to make us curious, excited and brave. Drugs such as cocaine and speed mimic the effect of dopamine, yet it is naturally stimulated when we win, fall in love, get promoted or enjoy extreme sports. However, these natural dopamine "highs" are as potentially addictive as the synthetic ones. The feelings of excitement that dopamine produces and the "hyped-up" sense of pleasure it brings can lead us to want more and more. And so we become addicted to computer games, 12-hour working days, alcohol, our partners, exercise, shopping or checking our phones — because when we stop these activities, we experience unpleasant withdrawal symptoms such as boredom, restlessness, inability to concentrate and anxiety. To rid ourselves of these uncomfortable feelings we continue with the dopamine-stimulating activity and, in doing so, the addictive loop of our problem habits is strengthened and sustained.

These days, our drive brain is frequently over-stimulated and dysregulated because we live in societies that encourage us to want more, have more and be more. Social comparison can be useful in helping us gauge how to fit in and belong to groups, however, it becomes debilitating and addictive when we constantly compare ourselves to unattainable, media-driven images of perfection. We push ourselves to achieve, accumulate, and compete but never feel that we measure up. Under these conditions, our drive brain is influenced by fear and other threat brain emotions aroused by the possibility of hostile judgment, criticism and social rejection. When drive and threat brain are both over-active, our bodies and minds become overdosed with a potent cocktail of hormones and chemicals including dopamine, cortisol, norepinephrine and adrenaline, which stimulate and stress us. If we are constantly experiencing this kind of over-drive, the chances are we will get stuck in toxic "loops" of addictive activity that represent our most problematic habits.

Unfortunately, many of us are unaware that our behaviours are sometimes or often influenced by threat, and that threat keeps us in a toxic drive loop. Or, if sometimes we do sense threat emotions pulsing within us, instead of trying to understand and soothe them, we deny, ignore, justify or rationalise the painful feelings, thoughts and behaviours that arise from them. Such psychological coping strategies — or defences — can work for a while, but because they do not deal with the source of our difficulties, our bodies and minds will suffer under the physical and mental strain of trying to repress or avoid the experiences that trigger our threat response.

It is our safe brain motivation system that enables us to both regulate threat and support healthy drive. Safe brain is activated by our parasympathetic nervous system, in particular by the hormone acetylcholine which slows the heart rate and enables us to relax, which in turn enables us to think clearly and deeply and to form trusting relationships with others. Whilst modern living does not offer enough opportunities to develop our safe brain capabilities, we can learn to do this for ourselves, starting with the re-direction of our attention.

First, we need to stop using external distractions or self-deception as a means for coping with our difficulties and instead begin to acknowledge and attend to what is going on within us. To interrupt our toxic-drive loops we need to notice and soothe the emotions of our threat brain using perception practices that re-balance our physiology and return us to "centre." From this place, we have greater freedom to choose how we understand our emotional reactions and what to do in response.

Perception practices re-direct our attention inward and develop our capacity to stay receptive and compassionate towards whatever emotions are arising. When we practice in this way, we learn to use our breath as an emotion regulator, our intuition for new perspectives, and our imagination to understand our deeper yearnings. Perception practices enable us to give greater expression to our own unique experiences and knowledge, and when we can do this, the allure of external distractions and solutions begins to diminish, along with the toxic-drive loops that perpetuate our suffering.

References

Wickremasinghe, N. (January 2021). Being with Others. Curses, Spells and Scintillations. Axminster, Triarchy Press.