Adolescence

Policy Responses to Teen Pregnancy

Teen Pregnancy Solutions Are at Hand

Posted July 9, 2015

By Laura Satkowski

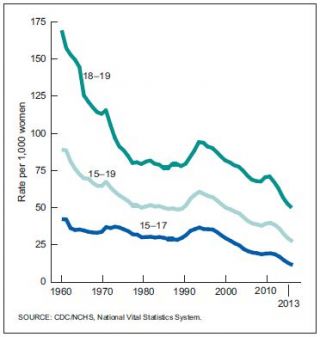

The United States has the highest teen pregnancy rate in the Western world (Holcombe, Peterson & Manlove, 2009), and most of these pregnancies are unintentional (Thomas, 2012). Teen mothers are less likely to finish high school and more likely to receive public assistance compared to women who delay childbearing. Their children are often born prematurely and suffer low birth weight, experience academic and behavioral issues in school, and are more likely to become teen parents themselves. What’s more, the issue of teen pregnancy doesn’t only affect teen parents and their children: children born to teens costs American taxpayers an estimated $9.2 billion each year in both immediate and long-term expenses related to medical care, welfare, and incarceration, among other costs. Although the teen birth rate in the U.S. declined steadily throughout the 1990s, the rate began to increase in 2006 and 2007 (Holcombe, Peterson & Manlove, 2009), but has been decreasing again in recent years (Martin et al., 2015).

Policy makers have pointed to the need for comprehensive sex education throughout the country to help remedy this national issue. One example of the effectiveness of this approach is California’s sex education policy. In the early 1990s, California had the highest teen pregnancy rate in the country; by 2005, the state had experienced the most rapid decline in teen pregnancy in the country. Their strategy began with an abstinence-only initiative, which proved politically popular but ineffective in reducing teens’ sexual activity. This led policymakers to shut down the program and renew their focus on decreasing the state’s teen pregnancy rate.

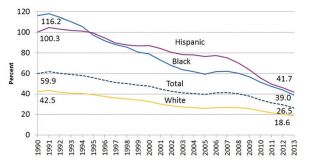

While the U.S. federal government began offering Title V grants to states for stringent abstinence-only sex education, California passed on the funding and, in 2003, signed the California Comprehensive Sexual Health and HIV/AIDS Prevention Education Act into law. This act required that all “school-based education programs be medically accurate, age-appropriate and comprehensive,” and must provide information on abstinence and all forms of contraception, including emergency contraception (Boonstra, 2010, p.19). In addition to this sex education policy, California established the Family Planning, Access, Care, and Treatment (Family PACT) program, which provides contraception at no cost to eligible low-income adolescents and adults. The program has excelled in reaching California’s Hispanic population, a population with a remarkably high teen pregnancy rate. In combination with several other media campaigns educating teens about safe sex practices and drawing media and policy attention to the issue of teen pregnancy, California has seen a halving in teen pregnancy rates between 1992 and 2005—from 157 in 1,000 to just 75 in 1,000 teen girls (Boonstra, 2010).

A different picture is painted in America’s southern states: while teen pregnancy rates have been decreasing in these states, the decline has been much slower than in other parts of the country. Nine states had rates of decline from 1992 to 2005 between 24-33 percent, compared to the national average of a 37 percent decline. Part of the issue may be that southern states are more likely to hold policies that require abstinence-only education, and to accept Title V federal funding for this education. Further, abortion policies and Medicaid eligibility are much stricter than those in other regions; for example, most southern states require some form of parental involvement in a minor’s decision to abort a pregnancy, and nine southern states require that Medicaid recipients earn less than 50 percent of the federal poverty level (Boonstra, 2010). Studies of outcomes related to sexual activity show that while abstinence-only education has little to no effect on the sexual practices of adolescents, comprehensive sex education has been associated with reduced sexual activity and increased contraceptive use among teens (Thomas, 2012). These findings point to the need for comprehensive sex education throughout the U.S.

Statutory Rape and Child Sexual Abuse Policy

Lack of comprehensive sex education may not be the only factor influencing teen pregnancy rates. One particular concern is the finding that teen pregnancies are often the result of sexual contact between a male over the age of 25 and a female under the age of 18 (Parikh, 2005). Urban, low-income, African American and Latino teens are at particularly high risk for both teen pregnancy and statutory rape. Furthermore, adult males are most often responsible for both sexual assault cases and instances of teen pregnancy. Adult males who father children with teen mothers often have behavioral issues, lower levels of education and income, and a history of cohabitation with minors (Kandaki & Smith, 2007).

Given that the majority of teen pregnancies are the result of sexual contact between a minor and an adult male, it is estimated that “as many as two thirds of teen births may be the result of statutory [rape]” (Kandaki & Smith, 2007, p. 173). Given that about 10% of births in the U.S. are to a teen (Thomas, 201

2), this figure represents a serious problem, made worse by the fact that definitions of statutory rape versus sexual abuse ar

e complicated and vary state-to-state. For example, while the federal government has a minimum definition of child sexual abuse, states are allowed to modify the definition. One third of states consider statutory rape to be child abuse (and thus reportable) only if the perpetrator is a caretaker of the child; otherwise it is reportable only if it is forcible rape. The remaining states have no such requirement and consider statutory rape to be a reportable crime. Many state laws only prosecute statutory rape offenders depending on the age difference between the offender and the minor, and this criteria also varies based on the age of the minor (Kandaki & Smith, 2007).

State-to-state variation in reporting procedures contributes to confusion regarding what constitutes statutory rape. Studies have shown that even among social service professionals who are familiar with reporting procedures and legal definitions of statutory rape and sexual abuse, the majority do not file these reports. Further, arrests are far less likely to occur if the father is identified as a boyfriend, and girls ages 13-17 are less likely to be legally protected by child sexual abuse laws than are younger children. The variation in child abuse and statutory rape laws, as well as the ambivalence of social service agents to report these cases, often leave adolescent girls responsible for unintended pregnancies that are the result of sexual contact with an adult male. Deviation in child sexual abuse and statutory rape laws, as well as lack of legal protection for older adolescents, is contributing to the problem of teen pregnancy in this country (Kandaki & Smith, 2007).

Summary and Recommendations

In light of the consequences and costs of teen childbearing and the recent increase in the teen birth rate in the U.S. from about 40 to 42.5 births per 1,000 females (Holcombe, Peterson & Manlove, 2009), policy changes are clearly imperative. First, comprehensive sex education should be the rule throughout the country, and federal grants should provide funding for these programs. States should be educated about research findings showing that comprehensive sexual education is far more effective than abstinence-only sexual education. Second, statutory rape and child sexual abuse definitions and laws should be well-defined in order to decrease confusion about what constitutes these crimes, and reporting procedures should be clearly outlined and mandated. Finally, information on these issues should be included in comprehensive sex education programs so all are aware of the laws and repercussions of these crimes. We must take responsibility as adults for the issues our adolescent girls are facing across the country, rather than allowing them to be taken advantage of by adult men, to view teen parenthood as one of the few things they can be successful at, and stigmatizing them for not rising above their circumstances. It is crucial that we make the necessary policy changes shown to be effective in reducing teen pregnancy.

Laura Satkowski is a Ph.D. Candidate in Applied Developmental Psychology at Fordham University.

References

Boonstra, H. D. (2010). Winning campaign: California’s concerted effort to reduce its teen pregnancy rate. Guttmacher Policy Review, 13(2), 18-24.

Edin, K., & Kefalas, M. (2011). Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Univ of California Press.

Holcombe, E., Peterson, K., Manlove, J., & Scarupa, H. J. (2009). Ten reasons to still keep the focus on teen childbearing. Research Brief, Publication# 2009-10. Child Trends.

Kandakai, T. L., & Smith, L. C. (2007). Denormalizing a historical problem: Teen pregnancy, policy, and public health action. American journal of health behavior, 31(2), 170-180.

Martin, J.A., Hamilton, B.E., Osterman, M.J., Curtin, M.A., & Matthews, T.J. (2015). Births: Final data for 2013. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Parikh, S. S. (2005). The other parent: A historical policy analysis of teen fathers. Building on Our Foundations, 5.

Thomas, A. (2012). Policy solutions for preventing unplanned pregnancy. Center on Children and Families at Brookings Institution. Retrieved March, 26, 2012.