Anxiety

As Child Anxiety Rises, Effective Treatment Proves Elusive

New research indicates preferred treatments often have poor long-term outcomes.

Posted July 14, 2018

Anxiety in children and teens often puts researchers on the horns of a dilemma. On the one hand, with the data they compile, they can point to social anxiety disorder and a litany of comparable conditions—e.g., GERD, female sexual dysfunction (FSD), and the “Low-T” testosterone campaign for men—as fairly clear-cut cases of disease mongering, where ordinary behaviors have been turned into treatable conditions. With all four conditions, research later uncovered, months of intensive marketing of the condition itself, prior to drug approval, more or less created both market and demand, hastening FDA action.

On the other hand, drawing heavily on those same criteria as the basis for their evidence, researchers frequently determine that anxiety disorders among children and teens are “prevalent” and “chronic,” with the numbers affected greatly on the rise. Those same criteria can of course lead to outcomes such as where one in seven American children is taking prescribed medication, for a small number of seemingly highly prevalent behavioral and anxiety disorders.

The research in both cases relies on diagnostic parameters that one school deems a “gold standard” in reliability, a phrase used in a recent study under review, while another school argues that such parameters have been expanded beyond all recognition by repeated bouts of “diagnostic bracket creep,” Peter Kramer’s invaluable term for diagnosis inflation. In this second scenario—and social anxiety disorder, particularly in children, can be seen as an awkwardly clear example of this—the goalposts are moved so far and so rapidly by each edition of the DSM that the diagnosis comes to fit ever-larger numbers of children and teens, including those experiencing broadly normal and predictable levels of anxiety.

That, at least, is the dilemma facing the authors of a large study of child and adolescent anxiety, published this month in the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. The University of Connecticut School of Medicine’s Dr. Golda Ginsburg and a team tied to seven other research institutions examined frequently prescribed treatments for children and teens meeting the diagnostic thresholds for social anxiety disorder, as well as for generalized anxiety and separation anxiety. And that's where the issue of reliable criteria becomes pressing.

“For the majority of pediatric patients,” the researchers conclude, “anxiety disorders are chronic, and additional treatment and relapse prevention approaches appear warranted.” Yet those same prevalence rates are tied to common, everyday indicators—often embarrassingly so in the case of young children. Included for example is language about “anxious anticipation,” as well as “freezing,” “shrinking,” and avoided “performance situations”—all official descriptors and criteria in DSM-IV, an edition of the diagnostic manual that also carries a warning about the risks of mistaking shyness for social anxiety disorder. In light of that warning, how, we might ask, can the same criteria be thought a “gold standard,” including for understanding the latest findings?

If we can put aside the question of prevalence for a moment, the study published in JAACAP is notable and valuable for its size (319 youths, with an age-range stretching from 10.9 to 25.2 years) and because of its insistent focus on relapse rates for frequently prescribed treatments for anxiety. These were studied across four years, an unusually long period, drawing attention to patterns often missed or mischaracterized by shorter studies.

Dr. Ginsburg’s team found that prescribed treatments for anxiety, such as the SSRI antidepressant sertraline (Zoloft), with and without cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), had significant failure rates across all four years, relative to placebo, with 48 percent relapsing overall and 30 percent still chronically ill afterwards. The researchers had “hypothesized that approximately 60 percent in the study would be in stable remission” after four years. Just 22 percent of youths in the study were.

The high levels of relapse over such commonly prescribed treatments for anxiety is notable and concerning. It means that “less than half of the sample met the rigorous criteria for stable remission,” greatly increasing “the need for enhanced treatment and relapse prevention strategies” for the growing numbers diagnosed with anxiety disorders.

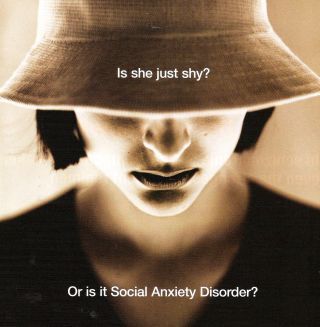

Still, the problem of diagnostic validity—inseparable from why prescribing rates are so stubbornly high in the first place—proves to be inescapable. Sertraline, the SSRI monitored in the study, was itself heavily marketed to prescribers in the early 2000s, ironically on the basis of the growing confusion over shyness and social anxiety disorder. Concerning a young woman photographed with a downcast gaze, the drug maker for Zoloft pointedly asked readers of the flagship American Journal of Psychiatry: “Is she just shy? Or is it Social Anxiety Disorder?” The point is, you couldn’t tell. No one could. Far from providing guidance, the DSM made either outcome possible.

Given its unusual size and likely influence, the JAACAP study draws invaluable attention to the unacceptably high relapse rates of those prescribed medication and CBT treatment for anxiety disorders. At the same time, for the same reason, it casts additional helpful light on the loose and baggy diagnostic criteria that have been used to measure prevalence rates, helping them balloon in scale.

We can put the dilemma at its starkest: If “freezing,” “shrinking,” and “anxious anticipation” continue to be seen as “the gold standard” for assessing social anxiety disorder, particularly in the very young, we can anticipate sky-high prevalence rates for decades to come.

References

Ginsburg, G. S., Becker-Haimes, E. M., Keeton, C., et al. (2018). "Results From the Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Extended Long-Term Study (CAMELS): Primary Anxiety Outcomes." Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(7), 471-80. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2018.03.017 [Link]