Fear

Why Does Polarization Happen?

The answer lies in how our brain is structured.

Posted October 24, 2022 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Political and social polarization is linked to how the brain works.

- The amygdala is largely responsible for the fight-or-flight reflex.

- Activating the fight-or-flight response preempts calmer evaluation of the viewpoints of others.

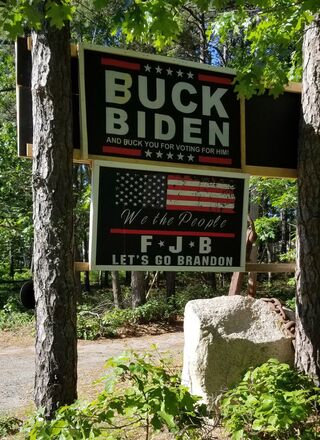

Down a road in the tiny, peaceful New England village where I currently live, a large sign is nailed to a tree. It curses the president of the United States, which is fair enough—in a democracy everyone is free to dislike a president. The sign goes a step further, though, and also curses anyone who voted for him. I have passed that sign a hundred times, and each time my reaction is the same—surprise, even shock at the rage, the anti-democratic intolerance motivating whoever put up that sign.

This always reminds me of the degree to which our politico-social life, in the U.S., has succumbed to polarization—and makes me want to get to the roots of why that has happened.

In my last post on "Shut Up and Listen," I described how humans' ability to explore and be curious—based in the hippocampal area of the brain—can be seen as balancing our tendency toward the freeze/fight/flight reflex: the fear reflex, essentially; largely situated in the amygdala. And it strikes me that this key dichotomy, in the current state of U.S. society, goes a long way toward explaining the polarization that has come to characterize so much of American political and social interaction.

Polarization—the tendency to increasingly cleave to one's own beliefs and the group that agrees with them, and to reject, deny, even attack the beliefs and affinity groups of others—is, through mechanisms of group-think and intolerance of uncertainty, almost always connected to an unwillingness or inability to learn in a systematic, objective way about the beliefs and characteristics of groups we don't agree with.

This, in turn, can be seen as stemming from a lack of empathy as well as a lack of curiosity about those groups.

As described in the previous post, the amygdala/hippocampus binome: fight or flight, versus curiosity and exploration; tends to be, if not entirely zero-sum, a case of emphasis on one preempting emphasis on the other.

It makes intuitive sense. If I'm reacting to someone with fear or with the intent to attack, I don't have time to explore who or what that person is, let alone find common ground with an individual I perceive as an enemy: Polarization, on an individual and ultimately a social level, can result.

Conversely, if I find the time and curiosity to learn about and empathize with that person, my ability to cooperate with her or him increases, leading to a decrease in hostility, and thus a lessening in this kind of polarization.