Bias

The Dead Keep a Record, Sometimes Disturbing

A deep sense of humanity pervades this medical examiner’s memoir.

Posted January 27, 2023 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Michael Baden measures a half-century of social issues through his most controversial autopsies.

- Anchored in science, he describes his rough ride through politics and racial bias.

- From Attica to George Floyd, Baden’s insider view reveals the price we might pay for the people we vote into power.

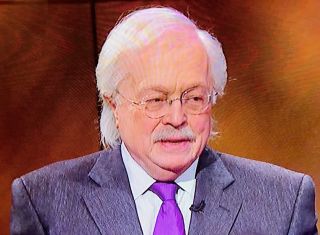

After a distinguished career as a medical examiner in various areas of New York, Michael Baden has written a compelling memoir, American Autopsy. It’s focused as much on social injustice as on his experiences in the autopsy suite. What he witnessed significantly informed his career trajectory. One line stands out as a central theme: “Death investigations mirror society.”

There’s a psychological side to any death investigation, including what motivates people in power and how they persuade others to be a “team player.” Attorney Peter Neufeld, co-creator of the Innocence Project, clarifies this in the book's afterword: “While multiple studies have described and analyzed how explicit and implicit racism have infected policing and the prosecutorial function, American Autopsy is unprecedented in revealing the critical role that forensic pathologists have been expected to play in helping convict the ‘bad guys’…while thwarting attempts to hold police accountable.”

It’s distressing to learn about the political compromises, reliance on junk science, lack of care for some populations, and plight of people with scant resources that Baden describes. Yet, he did what he could to improve some practices. For example, he created conditions for better oversight and prevention of suicides in prison by making the prison staff more accountable and by identifying key vulnerabilities, i.e., shoelaces and shower rods. He also contradicted official rulings, even when doing so would threaten his job, and worked pro bono to help ensure justice in cases that might otherwise have been covered up.

I interviewed Baden 20 years ago for Court TV’s Crime Library. Here’s how I started that piece: “Michael Baden, M.D. interprets the dead. He pays attention to the nuances of bruises and abrasions in ways that few people can.” In short, he was a medical detective. Yet, this new book shows that, thanks to politics, it’s not that simple. All investigations work within a system, and if the system is tainted, seeking the truth about someone’s death can get derailed.

Baden got his early training at Bellevue Hospital and the New York City's Medical Examiner’s Office. In the latter, he had a short-lived stint as its chief. He also became the state commission’s forensic pathologist and co-directed the Medicolegal Investigative Unit of the New York State Police. At one point, Baden chaired the Forensic Pathology Panel of the U.S. Congress Select Committee on Assassinations, which investigated the cases of President John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr.

The committee found that the Kennedy autopsy was badly botched: "One of the recommendations we made," said Baden, "was that there should be some national attention paid to improving death investigation in this country… Those doctors made lots of mistakes, such as creating false descriptions for why they couldn't find the bullet. They said it and they were wrong, and it lives with us even today."

The co-author of two earlier books, Unnatural Death: Confessions of a Medical Examiner and Dead Reckoning: The New Science of Catching Killers, Baden also hosted HBO's innovative Autopsy series. But Baden’s career has been controversial, in part because he decided that the medical examiner’s office would not be used as a tool to shield sloppy crime scene management and police misconduct. “I envisioned the office as independent, scientific, apolitical,” he writes. This memoir shows his side of those clashes. He witnessed plenty of racial bias in New York and around the country that deeply offended him. Initially interested in healing the living, a single case redirected him to forensic pathology.

Baden described it to me. "We had a patient who was a heroin addict who had an infection of the heart. In those days, that condition was difficult to treat and most patients with it died. We treated him and he survived, which was a real triumph. Then when I came down that weekend, there he was, dead on the autopsy table. He'd gone out and gotten back on heroin. We'd treated his infection but not his addiction. That made me think I could contribute more to society by looking at people on the autopsy table and feeding back the findings so that lots of people could benefit, rather than just treating patients one at a time."

People who pay attention to high-profile criminal cases know that Baden has been an investigator and expert witness in many of them, including those of Nicole Brown Simpson, Ted Binion, George Floyd, Phil Spector, Eric Garner, Jeffrey Epstein, and JonBenet Ramsey.

Baden challenges the practice of protecting people in power as he describes his involvement in the 1971 Attica tragedy, in which rioting prisoners were blamed for the deaths of hostage-guards. His reasoned, methodical approach to that volatile situation shows why he became such a prominent forensic pathologist. It also shows why he lost his standing with certain politicians. His chapter on the O.J. Simpson case reminds us of a turning point regarding forensics. Without this case, there might have been no C.S.I. and perhaps little to no oversight on the exploding field of forensic science.

However, Baden’s focus is on police misconduct and the country’s racial inequality: “We are at a pivotal moment in history. I believe it’s necessary to help the public understand how the criminal justice system really works.” Protection of power feeds a cognitive bias toward supporting smaller (often petty) personal goals over the greater good of humanity. Baden’s book will likely strike a chord in those who are trying to educate police on destructive forms of bias and on how to improve relations between cops and communities. Maybe pressure from the bottom up might erode the thug approach to “team player” politics as well. We can only hope.

References

Baden, M. (2023). American autopsy: One medical examiner's decades-long fight for racial justice in a broken legal system, BenBella Books.

Baden, M., Hennessee, J. A. (1989). Unnatural death: Confessions of a medical examiner. New York: Ivy Books.

Baden, M., & Roach, M. (2001). Dead reckoning: The new science of catching killers. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Stark, J. (2021). Addressing implicit bias in policing. Police Chief Magazine. https://www.policechiefmagazine.org/addressing-implicit-bias-in-policin…