Law and Crime

What Drives the Desire for "Murderabilia"?

The perceived value of an “aura” fuels the market for items linked to killers.

Posted May 9, 2022 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Some people see value in collecting items related to killers and their crimes.

- The "aura" of murder imbues objects with a sense of dangerous vitality.

- The collector community preserves the value of murder-related objects by affirming their perceived meaning.

Recently, I discovered that a page from a letter of mine to “BTK” killer Dennis Rader was for sale for $200. It outlined ideas for the work we were doing on his story, Confession of a Serial Killer, and Rader’s initials on it had raised its value. That is, he’d handled it, so someone would willingly pay to own it.

The same aura attaches to other items associated with serial killers and mass murderers, with some commanding surprisingly high prices. From museums to websites to large-scale expos, seekers can find nearly anything they want. But why? What drives them?

Andrew Dodge, a collector and host of the Unforbidden Truth podcast, says, “I collect murderabilia to preserve dark parts of history, from letters to artwork to prison IDs, which I have accumulated over the years from various offenders, as well as purchasing items for my collection. Although murderabilia is a taboo subject, it does provide insight to the psyche and world of the criminal.”

It was victim advocate Andy Kahan who coined the term "murderabilia." Meant to be derogatory, it’s become the accepted label for this morbid commerce. English professor David Schmid views the combination of celebrity and death as its force, arising from a mixed message in American culture: Our socially approved narrative about killers (they’re bad) is contradicted by a “disavowed” narrative (they’re fascinating). Thus, killers become glamorized, especially in covert venues. The more exposure a given figure achieved via an audience-grabbing story, the greater their celebrity allure.

True crime expert Harold Schechter states that collecting items that killers have touched or owned has roots in superstition. It’s a lucky charm; it protects. From those who'd dipped handkerchiefs into the bloody wounds of gangster John Dillinger to those who’ve purchased Ted Bundy’s car or Ed Gein’s gravestone, there will always be people who want to get close to items associated with violence and death.

The murderabilia market echoes the can't-turn-away attraction of battlefields, extreme sports, horror films, and even dangerous weather events. Throw in a bit of fame and the “contagion effect” of touching an item a killer has touched, and you begin to understand the hook. Crime scenes and murder trials have drawn gawkers since the 1800s, and the Internet’s reach has considerably enhanced visibility and access. It’s also provided a community of like-minded collectors. Taboo as the practice might be, there’s plenty of support.

Preserving a piece of criminal history is one motivator, but for some collectors, these objects also contain a covert vitality. People who receive a letter or drawing from Dennis Rader, for example, tell me how exciting—even scary—it is. Just opening the envelope filled them with awe. It stood out from every other piece of mail they'd received. It was from a serial killer. Such people have spurned the social frame of lawful behavior to unleash their rage, lust, desperation, or some other murder-inspiring emotion. They get as close to the divide between life and death as anyone can. Fascination with murder-related items expresses an attraction to energy that defies restrictive boundaries. So, there’s a marketplace to obtain them.

And it began with criminologists who hoped to educate.

Positivist theories during the late nineteenth century inspired the first criminological museums as teaching institutions. When Austrian criminologist Hans Gross attested to how quickly knowledge about crime became obsolete, museum developers decided to establish a visual history. In these museums, visitors could find skulls, death masks, execution instruments, weapons, poisons, crime tools, handwriting samples, criminal disguises, and even human remains.

The public demanded more, so vendors devised products. Once the market was established, its content was impossible to control. The buyers determined the value, as well as the permissible level of gore and depravity. Vendors obliged.

Psychologist Michael Apter suggests that once something is labeled “dangerous,” it exerts a magical attraction due to its heightened emotion. To reduce anxiety over approaching it, we develop "protective frames," i.e., narratives that provide buffers: The monster threatens us, but we can kill or cage him. Thus, we can safely experience the thrill of fear over what he’s done.

Considering the perceived transfer of a killer’s essence through murder items, this buffering concept applies. The meaning conveyed onto the object creates the frame, which maintains the sense of threat. Yet the killer’s not really there. Psychologically, a collector can experience the killer's aura from a safe distance.

Sometimes, the excitement peters out. I’ve talked with collectors who think the acquisition of murder items brought them bad luck, or they’ve grown too disturbed by it to keep it. They’ll likely find buyers. Since at least the 1980s, the demand for murderabilia has only grown.

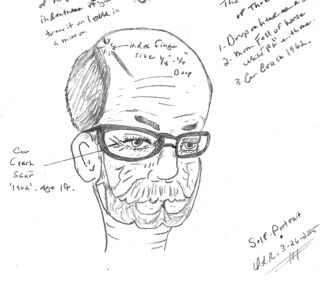

Today, one can find numerous online auction and sale sites. You might find a handwritten note from Ted Bundy, dirt from the body dumpsite of any number of killers, items used in a murder, signed handprints, and multiple artworks (including self-portraits). Reportedly, John Wayne Gacy had earned over $100,000 from his paintings. Most in-demand were his self-portraits dressed as a clown—adding one more disturbing layer.

References

Apter, M. (1992). The dangerous edge: The psychology of excitement. Free Press.

Binik, O. (2020). The fascination with violence in contemporary society. Springer.

Graham, M. (2006, December 8). Making a ‘murderabilia’ killing, Wired Magazine.

Regener, S. (2003). Criminological museums and the visualization of evil. Crime, History and Societies, 7(1).

Schechter, H. (2003). The serial killer files. New York: Ballantine.

Schmid, D. (2005). Natural born celebrities: Serial killers in American culture. University of Chicago Press.