Suicide

Do Serial Killers Leave Clues About Their Crimes After They Die?

Some offenders seal their legacy in death, as either the cat or the mouse.

Posted October 5, 2021 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- A recent suicide in France led to the identification of a previously unknown serial killer named Francois Vérove.

- Postmortem communications from killers can reveal their relationship to their crimes and to their demise.

- For some, their death is part of the games involved in their crimes.

This week, a retired French police officer, Francois Vérove, died by suicide after identifying himself in his suicide note as a “great criminal.” DNA taken from his body closed a longstanding series of cold cases from the 1980s and 1990s. His moniker at the time had been "Le Grêlé" ("the pockmarked one"), due to a witness description. As a married father of two, the 59-year-old had probably expected that he’d gotten away with his crimes. He was wrong.

Each time a serial killer dies, whether from natural causes or suicide, I’m often asked if they’d held things back. Ian Brady, for example, didn’t reveal where a missing victim was buried, and Rodney Alcala declined to admit to a murder that’s likely linked to him. Although it’s not always possible to know what they’ve kept to themselves, sometimes we do find dark secrets in their postmortem communications. Those who've played cat-and-mouse with cops can barely resist, but sometimes they just surrender – "You got me!"

In a suicide note, Vérove admitted to experiencing "previous impulses" but added that he’d straighten himself out after getting married and having a family. “I admit being a great criminal who committed unforgivable acts until the end of the 1990s.” According to press reports, he claimed he’d done nothing criminal since 1997.

Le Grele was believed to be responsible for at least six rapes and four murders. Among them was Cecile Bloch, an 11-year-old girl who’d been taken in May 1986 while she walked to school. She was found raped, stabbed, strangled, and placed under a carpet in the cellar of her apartment building.

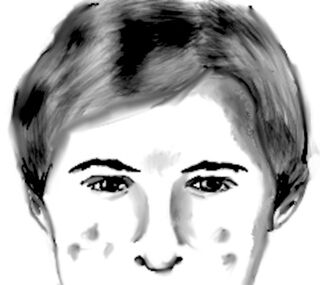

A witness who’d encountered a man with a pockmarked face helped police to make a drawing. They estimated the attacker to be age 25, six feet tall, with light brown hair. When the cases went cold, the drawing went onto the wall of the criminal brigade of the Paris judicial police. Vérove might even have seen it. DNA testing carried out years after this crime linked it to other incidents.

According to reports, Vérove has been deemed responsible for the murders of 38-year-old Gilles Politi and his 21-year-old au pair, Irmgard Mueller, who were both tortured. A woman and two underage girls were also raped. To lure his victims, Vérove reportedly identified himself as a police officer. (I've written about serial killer cops and cop pretenders here.)

He provided little description in his note, though he seemed to want acknowledgment that he’d stopped hurting people. Perhaps identifying himself was a show of remorse, but he likely knew DNA would inevitably out him. So he was the mouse, cornered and caught.

Another self-annihilating serial killer also left clues, but he remained the tantalizing cat. Israel Keyes used his suicide in 2012 to prolong his game with the FBI over his possible unknown victims. He’d admitted to killing three during extensive interrogations but only hinted at others. At one point, he said his victim toll was less than a dozen.

Just after 10 pm on December 1, a guard saw Keyes writing on a legal pad. During the night, Keyes died by suicide.

Guards found his body the next morning. Under his bed were papers on which he’d drawn a dozen skulls in blood, with the phrase, “We are one” written beneath them. He offered just one possible clue: “Belize.” (Maybe.)

The FBI lab found that most of what he’d written made little sense. The agents who worked the case believe the skulls represent his victims and himself, with him now as dead as them. That leaves eight more victims. But no one knows for sure. He apparently wanted the last laugh.

As increasingly more cold cases get solved with new leads or technology that can corner killers who thought they’d escaped, we might gain more such communications. Maybe notes that could solve some cases have already been planned... or written.