Serial Killers

The Meanest Man Who Ever Lived

Original documents show how arduous conditions helped to spawn a killer.

Posted July 6, 2020 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

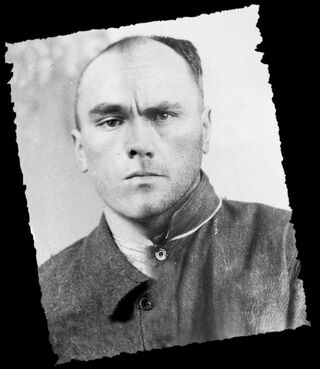

During the early twentieth century, Carl Panzram was an American serial killer whose international crime spree spanned multiple countries. He claimed to have killed 21 people (that he could recall), among thousands of other crimes from theft to rape. He also engaged in one of the most extraordinary prison friendships on record. A new book by John Borowski, Panzram at Leavenworth, provides a collection of impressive archival documents for his final imprisonment and execution.

Borowski is an author and award-winning filmmaker. He spent five years in Panzram’s labyrinth to make a comprehensive film about the killer’s life and crimes, Carl Panzram: The Spirit of Hatred and Vengeance. He thinks this killer's story is a cautionary tale with moral implications.

“Carl Panzram’s life of imprisonment, pain, and torture is an important lesson in how corporal punishment can create a hate-filled human being,” he told me. “Possibly even more important is the lesson of his jail guard, Henry Lesser, who exemplifies the example that choosing kindness over hate is a much better philosophy than ‘might makes right.’”

Of course, you can read Panzram’s own autobiography, Killer: A Journal of Murder, but Borowski brings more to the table regarding what led up to Panzram’s execution – a death he welcomed. Borowski focused on Panzram’s final stint, served at Leavenworth Penitentiary, where he brutally killed a prison official. He includes numerous press accounts to show how the media sensationalized the incident. The longer he searched for documents, the more he realized that the commonly told narratives were inaccurate. Using a federal file that no other biographer had tapped, Borowski sets the record straight. Like his other books of archived documents on serial killers, he provides enough to let readers ponder the matter and decide for themselves.

Borowski is one of the most meticulous researchers I know. He finds papers and files that are otherwise inaccessible, and he’ll track down rumors that pass as facts until he’s completely satisfied with their origin. He’s done other books like this on Ed Gein, Jeffrey Dahmer, Albert Fish, John Wayne Gacy, and H. H. Holmes, but this one’s more of an expose.

Panzram certainly got into trouble early. Arrested for drunkenness when he was only 8, he lived a hard life. He’d eventually referred to himself as “the spirit of meanness personified” and blamed endless abuse from family, religion, and prison guards for his foul temper and desire to kill. He murdered and raped indiscriminately and thought murder was fun. Whether there’s more weight in his development from nature or from nurture is the primary question. Borowski thinks it’s nurture – or rather, the lack of it.

Panzram was born in 1891 in rural Minnesota. His strict, religious parents had emigrated there from Germany. As a boy, he acted out to get attention, which drew swift punishment from his short-tempered father. He grew to resent his parents. By his own account, Panzram saved injustices like pennies in a piggy bank, watching for opportunities for payback. He took them all and added some extras for good measure.

Panzram burglarized neighboring homes, which got him a stint in the military-style Minnesota State Training School. He claimed he was whipped and raped there. Getting out, he turned to arson. He wanted nothing but revenge. After several more incidents in which he was victimized, Panzram decided he must act first to impose his will. Due to his unrelenting criminality, half his life was spent in some form of detention. In some places, he suffered brutal beatings, in part because he got into scraps with guards. No model prisoner, this irascible man was a magnet for abuse.

Psychiatrist Karl Menninger, who once took a keen interest in the convict, blamed Panzram's hostility on his treatment at the reform school. Menninger wrote that “the injustices perpetrated upon a child arouse in him unendurable reactions of retaliation which the child must repress and postpone but which sooner or later come out in some form or another, that the wages of sin is death, that murder breeds suicide, that to kill is only to be killed."

Panzram's final incarceration occurred in 1928. He confessed to having killed two boys and was sent to Leavenworth. He continued to be harshly disciplined. That's also when he found a friend.

Prison guard Henry Lesser took pity on him and gave him a dollar. Panzram was so surprised by this kindness that the two men began to chat. Soon, Panzram agreed to write his life story, and they made a clandestine arrangement: when Panzram had written fifteen or so pages, he’d leave it between the bars of his cell. When Lesser made his late-night rounds, he’d pick it up and supply more paper. In this 20,000-word confession, Panzram gave details of his crimes.

Panzram had warned that he’d kill any man who messed with him. Robert Warnke, the civilian laundry foreman, was the guy. They had a disagreement, and Panzram fatally bludgeoned him. You can get all the details on this incident in Borowski’s book.

Panzram went on trial for murder. Several eyewitnesses testified against him, and he refused to help his attorney. He was convicted and sentenced. On September 5, 1930, Panzram was hanged. Whether he uttered his famous last words about his executioners, said something else altogether, or said nothing at all before being hanged remains unclear. Borowski discusses this, too.

Panzram was proud of the murders he’d committed and only wished he’d managed a few more. He claimed to “hate the whole human race” and wished he could kill everyone.

As Borowski notes, his life offers a lesson about the effects on the human spirit of extreme abuse. Yet Lesser’s gesture was not the only kindness Panzram had received. He’d once been granted unsupervised outings, a trust he’d betrayed. His behavior provides a better measure of what he’d actually do than anything he claimed he might have done if only more people had been like Lesser. Even the letters to Lesser show Panzram’s impatience, one of the traits that got him in trouble.

I'm not as convinced as Borowski that Panzram could have been a finer man, but he offers a fascinating collection of documents on a killer who’s received little attention. Borowski's film is quite good as well.

References

Borowski, J. (2020). Panzram at Leavenworth. Chicago: Waterfront Productions.