Memory

Bundy and the Psychologists

Throughout Ted Bundy’s legal proceedings, psychologists offered analysis.

Posted February 28, 2020 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

As an undergraduate, Ted Bundy was a psychology major. Perhaps the infamous serial killer developed his MO of asking for help from a classic psychology experiment. The discipline seems to have played a key role throughout his life. From the moment he was first arrested in Utah until his final days in Florida, psychologists have turned their focus to him. I’ve written about Al Carlisle’s risk assessment of him here, and the twist in Bundy’s competency evaluation here. In this post, I focus on Elizabeth Loftus’ participation as a memory expert.

It started in Utah on November 8, 1974. A man posing as a cop tried to abduct a young woman named Carol DaRonch. According to her later report, he smelled of alcohol and acted oddly, so she stayed alert. He insisted that she get into his Volkswagen Beetle. She obeyed but remained wary. When he pulled out a gun and tried to handcuff her, she managed to get out of the car. He came at her with a crowbar. They struggled and she tore away and ran into the street. Waving down an approaching driver, she got help. Her attacker drove away. No suspect was picked up, but police remained watchful.

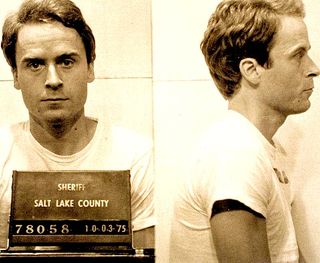

In August the following year, law student Ted Bundy was arrested outside Salt Lake City on suspicion of burglary. Officers wondered if there was a connection to DaRonch’s attacker, so they showed her a photo array that included Bundy. She identified him as her attacker. Utah authorities processed him for trial and prison psychologists evaluated him. Al Carlisle was one. He interviewed people who knew Bundy and found that the defendant had many faces. Despite his surface charm, he was a thief, liar, and con artist. He might even be the killer whom police in several states were looking for.

Bundy’s defense attorney, John O’Connell, knew he had to undermine DaRonch's identification. In December 1975, he contacted Elizabeth Loftus, an expert on eyewitness memory. She devotes a chapter to this experience in her book, Witness for the Defense. O’Connell believed that Bundy’s hope for acquittal depended on persuading fact-finders that there were significant problems with DaRonch’s identification. O’Connell admitted to Loftus that Bundy was a suspect in the “Ted cases” from the Pacific Northwest, but said no evidence connected him to DaRonch’s attack; there was just her identification and some type O blood drops on her clothing. Type O matched a large percentage of men. Unfortunately, Bundy could not establish an alibi.

O’Connell drew Loftus' attention to inconsistencies between DaRonch’s initial description to the police and her later recollections, as well as the increase over time of her level of confidence. She'd been hesitant at first and now she was certain. Something, he thought, was amiss. His instinct was right. In retrospect, thanks to memory researchers and several high-profile cases of mistaken ID, we know that post-event information, often introduced during police handling, can alter memory and influence eyewitness confidence.

Loftus examined the reports. DaRonch had initially described black shoes but changed to reddish-brown. She said the fake badge her attacker had flashed was all gold, but added more colors after an officer showed her a real badge. She described the car as white or light blue but changed this to beige (the actual color). Just an hour after the ordeal, she couldn’t recall key facts about her assailant, his car or his weapon. She could say only, "I don't know" or "I don't remember." The stress of her ordeal and the fear for her life, Loftus knew, had likely affected her recollections.

“When people are afraid,” she notes, “their memories slip and slide, neglecting details, rearranging facts. When we remember, we pull pieces of the past out of some mysterious region in the brain – jagged pieces that we sort and shift, arrange and rearrange until they fit into a pattern that makes sense… it is part fact, part fiction, a warped and twisted reconstruction of reality.”

There were other problems. DaRonch was first shown a photo of Bundy in a group of photos, but she wasn’t sure. O’Connell told Loftus that she’d hesitantly said, “I guess it looks something like him.” A few days later, an officer showed her a driver’s license photo of Bundy without the comparative context of other photos, and she said Bundy was the man. A month later, she picked him out of a line-up.

Loftus recognized possible unconscious transference: “By showing her two photos of the same man, the police could have created a memory in DaRonch’s mind. When she viewed the second photograph, she would have ‘remembered’ the face in the first photograph.”

The lineup occurred eleven months after the kidnap attempt – conditions for memory decay. DaRonch had seen Bundy’s picture twice before the line-up and had never seen the other participants. She’d also seen Bundy’s photo in the newspaper. It seemed possible to Loftus that DaRonch could have inadvertently identified an innocent man.

When Loftus agreed to testify, she states, it was no defense of Bundy; instead, it was an agreement to make a detached presentation of what she knew about memory from research. “It is my job,” she writes, “to be rational and clearheaded, to prevent emotions from swelling up and distorting reason, bending reality, twisting facts.”

Bundy was tried before a judge, not a jury, and Loftus was the defense’s star witness. She showed that common notions about memory operating as a video-recorder are untrue and misleading. Then she pointed out the inconsistencies in DaRonch’s statements, noting that her recollection seemed to have improved over time rather than worsened, as memory generally does. Rehearsal could have improved it, which can happen with trial prep. In addition, DaRonch's increased confidence could have derived from subtle cues from cops or attorneys who believed they had the right man. O'Connell thought these issues supported reasonable doubt.

In the end, on March 2, 1976, the judge found Bundy guilty of aggravated kidnapping. Loftus writes that he made his decision based on his own evaluation of Bundy: He just didn't believe Bundy's claim of innocence. Yet in her rendering of the trial, Loftus skipped Carlisle’s substantial report for the court. He made a strong case for Bundy’s deceptive, chameleonic character and likely potential to be dangerous in the future.

Loftus admits that she found Bundy’s reactions in court disconcerting. He was smiling and confident, more like a conman than an innocent one. Eventually, she learned that by the time he was caught in Utah, he’d killed numerous young women. However, this fact wouldn’t have changed her concerns with DaRonch’s ID. That wasn’t about Bundy; that was about memory. She thought the judge had taken her expert testimony seriously, but Bundy's own character had ultimately undermined him.

References

Loftus, E. & Ketcham, K. (1992). Witness for the defense. St. Martin’s.