Sex

Who Would Agree to Have Sex With a Stranger?

You might not. But many people would, especially men.

Posted June 28, 2017 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Choosing to have sex with a total stranger is not something everyone would do. It probably takes a certain type of person. Quite a bit of evidence suggests that, at least when it comes to eagerly having sex with strangers, it might also take being a man.

Let's look at the evidence.

Over the last few decades almost all research studies have found that men are much more eager for casual sex than women are (Oliver & Hyde, 1993; Petersen & Hyde, 2010). This is especially true when it comes to desires for short-term mating with many different sexual partners (Schmitt et al., 2003), and is even more true for wanting to have sex with complete and total strangers (Tappé et al., 2013).

In a classic social psychological experiment from the 1980s, Clark and Hatfield (1989) put the idea of sex differences in consenting to sex with strangers to a real-life test. They had experimental confederates approach college students across various campuses and ask, "I've been noticing you around campus. I find you to be very attractive. Would you go to bed with me tonight?" Around 75 percent of men agreed to have sex with a complete stranger, whereas no women (0 percent) agreed. In terms of effect size, this is one of the largest sex differences ever discovered in psychological science (Hyde, 2005).

Twenty years later, Hald and Høgh-Olesen (2010) largely replicated these findings in Denmark, with 59 percent of single men and 0 percent of single women agreeing to a stranger's proposition, “Would you go to bed with me?” Interestingly, they also asked participants who were already in relationships, finding that 18 percent of men and 4 percent of women currently in a relationship responded positively to the request.

According to Strategic Pluralism Theory (Gangestad & Simpson, 2000), men of high physical attractiveness should be most able to successfully pursue a short-term sexual strategy (physical attractiveness fulfills women's evolved preferential short-term mating desires). For the average-looking man, short-term mating may not represent a viable reproductive option (Schützwohl et al., 2009; see also here).

OK, but Why?

Several scholars have modified the experimental "ask for sex" method to see if they could tell why men, but not women, agreed to sex with strangers. Clark (1990) was among the first to address the issue of physical safety. He had college-aged confederates call up a personal friend on the phone and say "I have a good friend, whom I have known since childhood, coming to Tallahassee. Joan/John is a warm, sincere, trustworthy, and attractive person. Everybody likes Joan/John. About four months ago, Joan/John’s five-year relationship with her/his high-school sweetheart dissolved. She/he was quite depressed for several months, but during the last month Joan/John has been going out and having fun again. I promised Joan/John that she/he would have a good time here, because I have a friend who would readily like her/him. You two are just made for each other. Besides, she/he has a reputation as being a fantastic lover. Would you be willing to go to bed with her/him?” Again, many more men (50 percent) than women (5 percent) were willing to have sex with this personally "vouched for" stranger. When asked, not one of the 95 percent of women who declined sex reported that physical safety concerns were a reason.

Surbey and Conohan (2000) wondered whether worries of safety, pregnancy, stigma, or disease were holding women back from saying yes to sex with a stranger (see also Pipitone et al., 2021). In a "safe sex" experimental condition, Surbey and Conohan asked people, "If the opportunity presented itself to have sexual intercourse with an anonymous member of the opposite sex who was as physically attractive as yourself but no more so (and who you overheard a friend describe as being a well-liked and trusted individual who would never hurt a fly), do you think that, if there was no chance of forming a more durable relationship, and no risk of pregnancy, discovery, or disease, that you would do so?" On a scale of 1 (certainly not) to 4 (certainly would), very large sex differences still persisted with women (about 2.1) being much less likely to agree with a "safe sex" experience with a stranger compared to men (about 2.9).

Safety concerns can also be addressed by examining men's and women's sexuality across varying sexual orientations. Among lesbians, for instance, safety concerns about the greater strength of opposite sex mates are not present. Schmitt (2008) examined men's and women's attitudes toward casual sex around the world and found wherever you go lesbians tend to have the same sexual attitudes as heterosexual women (and gay men have the same attitudes as heterosexual men). Moreover, in every region he examined, regardless of orientation, men tended to have more positive attitudes toward casual sex as women. However, because gay men have other men as their potential mating partners (whereas women have other women), gay men tended to engage in more casual sex than heterosexual men (d = .55). Lesbians, with women as potential mates, did not differ much in casual sex from heterosexual women (d = .18). And the differences between heterosexual men and women (d = .73) where much smaller than the differences between gay men and lesbians (d = 1.11). Under gender-target controlled conditions, sex differences in casual sex appear to reveal themselves even further.

Some have wondered whether men's greater tendency to succumb to sexual temptations might result, not from men's desires, but from women's tendency to have greater control over themselves. In a series of experiments, Tidwell and Eastwick (2013) found this was not the case. Instead, their research found "men succumbed to the sexual temptations more than women, and this sex difference emerged because men experienced stronger impulses, not because they exerted less intentional control."

So, sex differences in agreeing to sex with strangers are not just a matter of safety issues, pregnancy concerns, stigma, disease avoidance, or self-control. Controlling for all of that, researchers still find large sex differences in sexual behavior, including the willingness to have sex with a stranger.

Converging Lines of Evidence

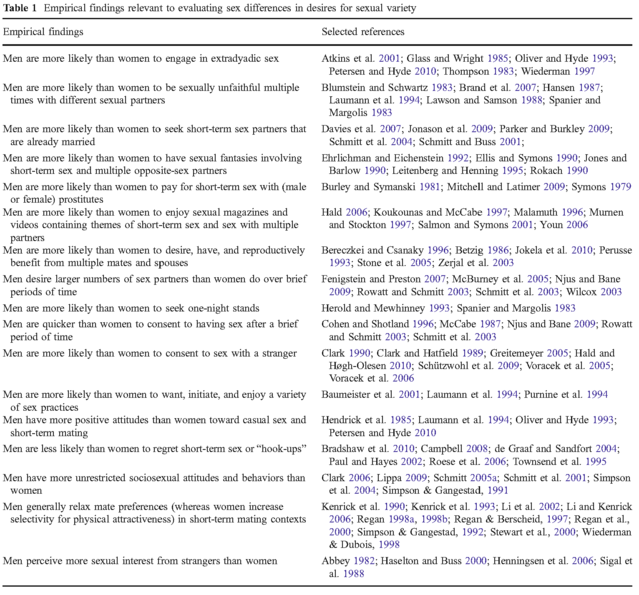

In addition to these powerful experimental tests, a wide range of supportive evidence (literally hundreds of studies) confirms that men, on average, are more eager than women are for casual sex and tend to desire sex with more numerous partners, including complete strangers (Buss & Schmitt, 2011).

In terms of research on sexual attitudes, nearly all studies conducted have found that men have more positive attitudes toward casual sex than women (Oliver & Hyde, 1993; Petersen & Hyde, 2010), have more unrestricted sociosexuality than women (Schmitt, 2005), and generally relax their preferences in short-term mating contexts (whereas women increase selectivity, especially for physical attractiveness; Buss & Schmitt, 2011).

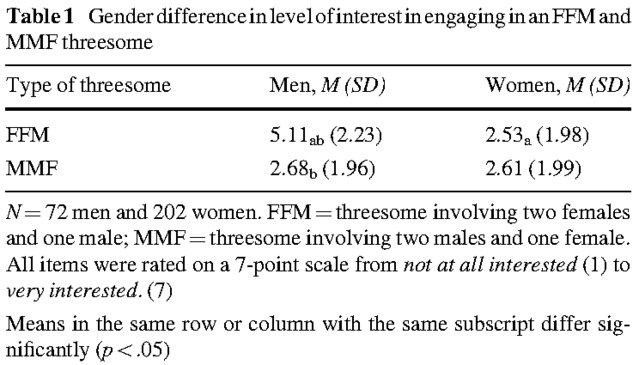

When considering attitudes toward mixed-sex threesomes, for instance, most people express very little interest, with the notable exception being men considering having sex with two women at the same time, even if they are strangers (Thompson & Byers, 2016).

Many more men (24%) than women (8%) are willing to engage in a consensually non-monogamous relationship (i.e., a committed romantic relationship wherein everyone consents to all partners having multiple sexual encounters with others; Sizemore & Olmstead, 2017). In a national survey of USA adults, more men than women said they would find having sex with stranger "very" or "somewhat appealing" (39% versus 12%; Herbenick et al., 2017), about the same sex difference found for the appeal of having a threesome (34% of men, 11% of women).

Although men say they are more interested in various forms of short-term mating, though, perhaps women would do so if it were not socially undesirable to do so? Well, as noted above, experimental real-world tests suggest women are much less likely to consent to sex with strangers than men are. Moreover, Schmitt (2005) looked at the response bias of impression management associated anonymous, self-reported sociosexuality and found both men’s and women’s responses are just about equally effected. That is, typically both women's AND men's sociosexuality are reduced when controlling for impression management. Sex differences in sociosexuality in the USA are reduced from d = .63 to d = .57 after controlling for impression management, for example. About a 10 percent reduction in the size. Not explained away by any means.

Another clue that women really do have less positive attitudes toward casual sex is research using the bogus pipeline procedure. Alexander and Fisher (2003) did a “bogus pipeline” study using three experimental conditions: 1) hooking people up to a (fake) lie detector and having them complete sex surveys (the lie detector was intended to elicit the highest levels of truthfulness), 2) having people complete sex surveys anonymously (which is what all sex researchers should do, by the way), or 3) having people complete sex surveys with a researcher conspicuously in the room when they were non-anonymously asked about sexuality (lowest truthfulness expected here, of course). Sex differences in sexual attitudes (as measured by the Sexual Opinion Survey—a basic measure of erotophilia) remained significant across all three testing conditions. Sex differences were largest in the non-anonymous condition (d = .71). Crucially, the size of the sex difference remained stable across the anonymous (d = .37) and lie detector conditions (d = .36). This result confirms responses to sex surveys under anonymous conditions are as valid as when administered under a lie detector condition. So, sex differences in sexual attitudes do not "disappear" from view when men and women are presumably more likely to tell the truth. They are the same as when people are given true feelings of anonymity when completing sex surveys (which most sex researchers know to do; Robertson et al., 2018).

Cognitively and emotionally, men are more likely than women to have sexual fantasies involving short-term sex and multiple opposite-sex partners; men perceive more sexual interest from strangers than women do; and men are less likely than women to regret short-term sex or “hook-ups.” For instance, Weitbrecht and Whitton (2017) found in an study of hook-ups that "a greater proportion of men (62.5%) than women (11.3%) endorsed continued sexual involvement as ideal, while more women (60%) than men (12.5%) indicated romantic involvement as the ideal outcome of their most recent encounters."

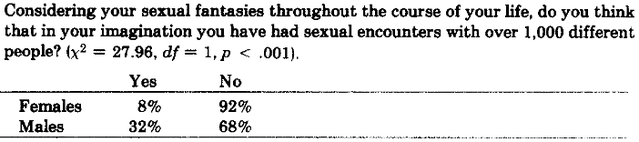

Considering sexual fantasies, men are much more likely than women to report having imagined sex with more than 1,000 partners in their lifetime (Ellis & Symons, 1990).

Behaviorally, men are more likely than women to be willing to pay for short-term sex with (male or female) prostitutes. For instance, in a study of 852 randomly chosen people across Denmark and Sweden, Jæger et al. (2000) found 16% of men have paid for sex with a prostitute. The equivalent statistic for women who have paid for sex with a prostitute...0%. Are these results limited to Danish and Swedish men? According to ProCon.org, the upper estimates of men who have paid a prostitute for sex around the world are: Italy = 45%, Spain = 39%, Japan = 37%, Netherlands = 22%, USA = 20%, China = 20%, Swiss = 19%, France = 16%, Australia = 16%, Sweden = 14%, Finland = 13%, Norway = 13%, and UK = 9%. They do not report the % of women across these nations who have paid for sex, though what would be your best guess? Why does it appear that women do not need to pay for short-term sex? Could it be that men, on average, are more eager than women are for casual sex and tend to desire sex with more numerous partners, including complete strangers?

Additional behavioral evidence comes from robust findings that men are more likely than women to enjoy sexual magazines and videos containing themes of short-term sex and sex with multiple partners; men are more likely than women to actually engage in extradyadic sex; men are more likely than women to be sexually unfaithful multiple times with different sexual partners; men are more likely than women to seek one-night stands; and men are quicker than women to consent to having sex after a very brief period of time (for citations, see Buss & Schmitt, 2011).

In a 2017 study of the many complex motivations behind wanting extradyadic sex, the largest sex difference was in the motivation for sexual variety (d = .64), which was a larger sex difference than men's greater levels of having extradyadic sex because of general sexual desire (d = .39) or women's greater levels of having extradyadic sex because of feeling neglected (d = -.38) or having a lack of love at home (d = -.11; Selterman et al., 2017).

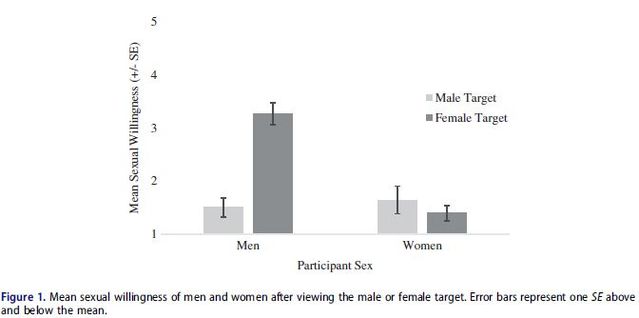

In a 2018 study, Helmers et al. (2018) asked men and women the extent with which they would be willing to have sex with an attractive stranger at a bar. Again, men were much more likely than women to be willing to do so with an opposite sex partner. For women, they were relatively unlikely to do so, about equally unlikely whether the stranger was a man or a woman.

Is Patriarchy to Blame?

Many of these sex differences are culturally universal, having been observed in dozens of samples around the world (Lippa, 2009; Schmitt, 2005). One might claim universal features of "patriarchy" or "sex role socialization" are primarily responsible for this sex difference universality, and this is certainly partly true (though that doesn't make these sex differences a "myth" and merely adds more to be explained). Moreover, there are serious questions as to patriarchy and sex role socialization being the only explanations.

For instance, in a large cross-cultural study involving 58 nations (i.e., the ISDP-2), Schmitt (2015) found sex differences in the sociosexuality scale item, "I can imagine myself being comfortable and enjoying ‘casual’ sex with different partners,” were largest in nations with the most egalitarian sex role socialization and the greatest sociopolitical gender equity (i.e., the least patriarchy, such as in Scandinavia). This is exactly the opposite of what we would expect if patriarchy and sex role socialization are the prime culprits behind sex differences in consenting to sex with strangers.

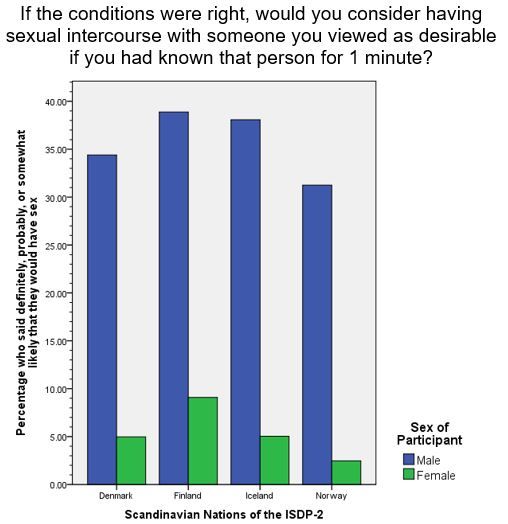

Similarly, when Schmitt asked men and women of the ISDP-2, "If the conditions were right, would you consider having sexual intercourse with someone you viewed as desirable if you had known that person for 1 minute?" he found sex differences were prevalent around the world. In Scandinavia, very large sex differences were found, as shown in the chart below:

How can this be? Why are these sex differences larger in gender egalitarian Scandinavian nations? According to Sexual Strategies Theory (Buss & Schmitt 1993), among those who pursue a short-term sexual strategy, men are expected to seek larger numbers of partners than women (Schmitt et al., 2003). When women engage in short-term mating, they are expected to be more selective than men, particularly over genetic quality (Thornhill & Gangestad, 2008). As a result, when more egalitarian sex role socialization and greater sociopolitical gender equity “set free” or release men’s and women’s mating psychologies (which gendered freedom tends to do), the specific item “I enjoy casual sex with different partners” taps the release of men’s short-term mating psychology much more than it does women’s. Hence, sex differences on “I enjoy casual sex with different partners” are largest in the most gender egalitarian nations.

Overall, when looking across cultures, reduced patriarchy doesn't make these and most other psychological sex differences go away; it makes them larger (Schmitt, 2015). So much for blaming patriarchy and sex role socialization.

Deceive, Inveigle, Obfuscate

Despite this wealth of confirmatory evidence--as evidenced in real life experiments (controlling for many confounds and alternative explanations), numerous meta-analyses of sexual attitudes, and decades of work on sex differences in sexual cognition, fantasy, emotion, and behavior--some scholars have deemed the notion that men are more eager than women are for sex with complete strangers as a total "myth" (Rudman, 2017). Like extreme climate change deniers1, some of these scholars focus on a few contrived studies, torture the findings into a false narrative, and then claim that a few new empirical results completely refute a mountain of well-established evidence. Below I explain why two particular studies commonly used in this manner do not refute the mountain of evidence supporting sex differences in willingness to have sex with strangers. In fact, they are very much a part of the mountain.

Baranowski & Hecht (2015): Sex With Strangers at a Party and in a Lab

Baranowski and Hecht (2015) conducted two experiments relevant to assessing whether men and women differ in willingness to have sex with a stranger. In Experiment 1, they had confederates approach participants at a "party" (at the bar, dance floor, or a smoking area at night). Confederates were instructed to approach unknown members of the opposite sex who were without obvious company and say, "Hi, normally I don’t do anything like this, but I find you totally attractive. Would you like to have sex with me?"

In this "party" condition, Baranowski and Hecht found 50 percent of men (19 out of 38) agreed to sex with a total stranger (including 16 percent of men at the party who were already in a relationship—that’s a lot of willing male extra-pair copulators). In contrast, only one woman (4 percent) agreed to have sex with a stranger (and she was not in a relationship). In a second "on campus" condition, 14 percent of men and 0 percent of women agreed to sex with a complete stranger. Clearly requests at parties are more conducive to stranger sex than requests on campus (at least for men). Also clear from this first experiment is that men are more receptive to requests for sex from total strangers.

In a second experiment, Baranowski and Hecht presented participants with a complex sequence of "dating study" experiences over time. Eventually, participants were brought into a university lab and were shown pictures of 10 people who presumably had previously reported they wanted to either "date" or "have sex" with the participant. If the participant then chose any of the pictures to date or have sex with in return, the researchers said they would then film an hour discussion between the interested individuals and then leave them to have a date or have sex in a safe laboratory environment. (This is legal in Germany where the study was conducted.)

What were the amazing "there are no sex differences in desires for having sex with a stranger" findings? From the original article: “Of all male subjects, 100 percent agreed to have a date or sex with at least one woman. This rate did not differ from the female consent rate (97 percent).” Did you notice that? Those results were for "date or sex." Nowhere was it reported what the percentages were of men versus women specifically agreeing to have sex. As it stands, it might be that men agree to a date 1 percent of the time and to sex 100 percent of the time (unlikely, but possible), whereas women agree to a date 97 percent of the time and to sex 1 percent of the time. Because of this double-barreled reporting, we simply can't know what the truth is about sex differences in wanting to have sex with strangers from the published Baranowski and Hecht (2015) percentage results.

It's unbelievable that these results were published in this form, or that serious scholars would claim this published study is definitive proof that sex differences in consenting to sex with strangers are a "myth" (Rudman, 2017). Indeed, in order to do so they misinform readers about the findings, such as Rudman's (2017) claim "100 percent of the men and 97 percent of the women agreed to potentially have sex with at least one stranger, which did not statistically differ." Did you catch that? Rudman claimed the 100 percent versus 97 percent is just about sex with a stranger. Well, the Baranowski and Hecht published data specifically cited by Rudman were about the "date or sex" with a stranger findings. There were no percentage findings for just the sex condition in the published Baranowski and Hecht (2015) data.2

Most importantly, Baranowski and Hecht (2015) did report the raw number of strangers that men and women agreed to have sex with in their Experiment 2. These key data are actually relevant for evaluating Rudman's (2017) claim that sex differences in consenting to sex with strangers are a "myth." The findings? Men chose a larger number of strangers to have sex with (M = 3.57; SD = 1.16) than women did (M = 2.73; SD = 1.87), a moderately-sized sex difference, d = .56, even a little larger than the German sex difference in sociosexuality reported in the International Sexuality Description Project (d = .48; Schmitt, 2005).

So sex differences in consenting to sex with strangers did not disappear in this research study: Baranowski and Hecht (2015) clearly found sex differences in consenting to sex with strangers in both of their experiments. And in Experiment 2, the only reported data with which they precisely evaluated that question — which is number of strangers chosen for sex — there was a moderately-sized sex difference, d = .56. This is even larger than meta-analytic sex difference in attitudes to casual sex, d = .46 (Petersen & Hyde, 2010). And again, it's also a little larger than the German sex difference in sociosexuality reported in the International Sexuality Description Project (d = .48; Schmitt, 2005). Converging lines of evidence, indeed.

Sex With Strangers vs. Sex With Celebrities

In 2011, Conley conducted an American version of the “ask for sex” methodology using hypothetical requests from unknown strangers and celebrities. (This study did not involve actual real-life requests.) Although her theoretical portrayal of evolutionary psychology was highly flawed (see Schmitt et al., 2012), her results were quite interesting (and again, supportive of the mountain of evidence that men and women differ in desires for sex with strangers).

Most importantly, Conley (2011) found in an "unknown stranger" condition there were very large sex differences in willingness to have sex with strangers. Using a rating scale, Conley found 74 percent of men would "entertain the possibility of the sexual offer" (rating between two and seven on a likelihood scale) whereas only 18 percent of women would. This is a key confirmation, of course, when it comes to directly testing whether there are sex differences in willingness to have sex with strangers. But it is often missed given the study's celebrity findings.

Within the highly attractive celebrities condition, Conley (2011) found women were much more likely to agree to a brief sexual encounter with a high-profile celebrity (e.g., Brad Pitt, Johnny Depp) compared with an unknown stranger, but men were relatively unaffected by a stranger's celebrity status (men were hypothetically asked for sex by Angelina Jolie or Jennifer Lopez, but men were rather willing to have sex regardless of a woman's celebrity status). As a result, sex differences in reactions within the celebrity requests for sex condition were minimal. However, these findings with celebrity requests for sex did not disconfirm or deem a "myth" that there are evolved sex differences in short-term mating psychology and desires for sex with strangers. In fact, these findings confirmed evolutionary perspectives on short-term mating psychology in several ways.

For instance, the celebrity findings confirm the view that women's (but not men's) short-term mating psychology is specially designed to obtain good genes from physically attractive partners (Thornhill & Gangestad, 2008). Brad Pitt and Johnny Depp are extremely attractive, as are Angelina Jolie and Jennifer Lopez, but as predicted by an evolutionary perspective, women's short-term desires for sex with strangers were more profoundly affected by this extreme attractiveness.

The Conley (2011) study also used participants who were only 22 years old on average to consider sex with much older celebrities, celebrities who also were married. As evolutionary psychologists have pointed out, women in their 20s generally prefer older partners as short-term mates compared to men (Buunk, Dijkstra, Kenrick, & Warntjes, 2001), and women tend to find already-mated prospective partners especially attractive (Parker & Burkley, 2009). Brad Pitt and Johnny Depp (highly attractive, more than 10 years older, married) are among the most adaptively-potent designed humans when it comes to fulfilling women’s (but not men’s) evolved short-term mate preferences as outlined by Sexual Strategies Theory (Buss & Schmitt, 1993).

In short, the Conley (2011) research method was highly contrived to provide a special set of conditions within which men and women would appear not to differ in choosing to agree to casual sex (celebrities who are attractive, older, married, etc.). But the sex-similar results within this special condition are expected from an evolutionary perspective.

Indeed, given other findings on women’s evolved short-term psychology, such as women who are nearing ovulation and are already in relationships with asymmetrical and submissive partners being more likely to consent to sex with extremely attractive men (Pillsworth & Haselton, 2006), there may be certain contexts in which women are more likely than men to consent to short-term sex. That's right, evolutionary psychologists argue that women are highly designed for short-term mating (Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Gangestad & Simpson, 2000; Kenrick et al., 1990). Just not designed in the same way as men.

So these special contextual factors utilized by Conley (2011) do not demonstrate that men and women have identical desires underlying their seemingly similar choices. The similar-looking choices result from a foundation of women (but not men) having specialized desires for short-term mating with highly attractive, older, and perhaps even married people; whereas men are interested in short-term mating regardless of these particular factors.

In the end, this is the key point of the Conley (2011) study: It takes Johnny Depp to get women to even consider agreeing to casual sex. For men, the difference between agreeing to sex with Jennifer Lopez versus a total stranger was minimal. The Baranowski and Hecht (2015) study clearly found sex differences in consenting to sex with strangers in both of their experiments. These facts should tell you a lot about the reality of sex differences in short-term mating psychology and willingness to have sex with strangers. And these facts do not stand alone.

It is certainly possible that psychological science could accumulate additional evidence that would tip the scales against thinking that men possess psychological adaptations that lead them, on average, to be more accepting of and interested in casual sex, especially low-investment sex with complete strangers. As scientists, one should always keep an open mind and be on the lookout for new disconfirmatory evidence, and appropriately place this evidence within existing explanatory structures (Ketelaar & Ellis, 2000). Given the breadth and depth of evidence on this topic, though, any new supposedly revelatory studies should, to paraphrase Carl Sagan, be extraordinary. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. Critically, to be taken seriously this new evidence would need to account for the mountain of evidence that already exists on sex differences in the psychology of casual sex--meta-analytic, experimental, cross-cultural, cross-species, and more (Buss & Schmitt, 2011; Schmitt & Pilcher, 2004). Completely ignoring decades of existing evidence, or deliberately distorting it, should not be acceptable scientific options.

Facebook image: MJTH/Shutterstock

References

References

Alexander, M. G., & Fisher, T. D. (2003). Truth and consequences: Using the bogus pipeline to examine sex differences in self‐reported sexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 40, 27-35.

Baranowski, A.M., & Hecht, H. (2015). Gender differences in and similarities in receptivity to casual sex invitations: Effects of location and risk perception. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 2257–2265. doi:10.1007/s10508-015-0520-6

Buss, D.M., & Schmitt, D.P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100, 204–232.

Buss, D.M., & Schmitt, D.P. (2011). Evolutionary psychology and feminism. Sex Roles, 64, 768-787.

Buunk, B.P., Dijkstra, P., Kenrick, D.T., & Warntjes, A. (2001). Age preferences for mates as related to gender, own age, and involvement level. Evolution & Human Behavior, 22, 241–250.

Clark, R. D. (1990). The impact of AIDS on gender differences in willingness to engage in casual sex. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 20, 771-782.

Clark, R.D., & Hatfield, E. (1989). Gender differences in receptivity to sexual offers. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 2, 39–45. doi:10.1300/J056v02n01_04

Conley, T.D. (2011). Perceived proposer personality characteristics and gender differences in acceptance of casual sex offers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 309–329. doi:10.1037/a0022152

Diethelm, P.A., McKee, M. (2009). Denialism: what is it and how should scientists respond? European Journal of Public Health.,19, 2–4.

Ellis, B. J., & Symons, D. (1990). Sex differences in sexual fantasy: An evolutionary psychological approach. Journal of Sex Research, 27, 527-555.

Gangestad, S.W., & Simpson, J.A. (2000). The evolution of human mating: Trade-offs and strategic pluralism. Behavioral & Brain Sciences, 23, 573–644.

Hald, G.M., & Høgh-Olesen, H. (2010). Receptivity to sexual invitations from strangers of the opposite gender. Evolution & Human Behavior, 31, 453–458.

Helmers, B. R., Harbke, C. R., & Herbstrith, J. C. (2018). Sexual willingness with same-and other-sex prospective partners: Experimental evidence from the bar scene. The Journal of Social Psychology, 158, 109-124.

Herbenick, D., Bowling, J., Fu, T. C. J., Dodge, B., Guerra-Reyes, L., & Sanders, S. (2017). Sexual diversity in the United States: Results from a nationally representative probability sample of adult women and men. PloS one, 12(7), e0181198.

Hyde, J.S. (2005). The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psychologist, 60, 581-592.

Jæger, A. B., Gramkow, A., Sørensen, P., Melbye, M., Adami, H. O., Glimelius, B., & Frisch, M. (2000). Correlates of heterosexual behavior among 23–87 year olds in Denmark and Sweden, 1992–1998. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 29, 91-106.

Kenrick, D. T., Sadalla, E. K., Groth, G., & Trost, M. R. (1990). Evolution, traits, and the stages of human courtship: Qualifying the parental investment model. Journal of Personality, 58, 97-116.

Ketelaar, T., & Ellis, B. J. (2000). Are evolutionary explanations unfalsifiable? Evolutionary psychology and the Lakatosian philosophy of science. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 1-21.

Lippa, R. A. (2009). Sex differences in sex drive, sociosexuality, and height across 53 nations: Testing evolutionary and social structural theories. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 631–651.

Oliver, M.B., & Hyde, J.S. (1993). Gender differences in sexuality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 29-51.

Parker, J., & Burkley, M. (2009). Who’s chasing whom: The impact of gender and relationship status on mate poaching. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 1016–1019.

Petersen, J.L., & Hyde, J.S. (2010). A meta-analytic review of research on gender differences in sexuality, 1993–2007. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 21–38.

Pillsworth, E.G., & Haselton, M.G. (2006). Male sexual attractiveness predicts differential ovulatory shifts in female extra-pair attraction and male mate retention. Evolution & Human Behavior, 27, 247–258.

Pipitone, R. N., Cruz, L., Morales, H. N., Aladro, D., Savitsky, S. R., Koroleva, M., ... & Miranda, S. (2021). Sex differences in attitudes toward casual sex: Using STI contraction likelihoods to assess evolved mating strategies. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 706149.

Robertson, R. E., Tran, F. W., Lewark, L. N., & Epstein, R. (2018). Estimates of non-heterosexual prevalence: the roles of anonymity and privacy in survey methodology. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47, 1069-1084.

Rudman, L.A. (2017). Myths of Sexual Economics Theory: Implications for Gender Equality. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 0361684317714707.

Schmitt, D.P., Alcalay, L., Allik, J., Ault, L., Austers, I., Bennett, K.L., . . . Zupanèiè, A. (2003). Universal sex differences in the desire for sexual variety: Tests from 52 nations, 6 continents, and 13 islands. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 85–104.

Schmitt, D.P., Jonason, P.K., Byerley, G.J., Flores, S.D., Illbeck, B.E., O’Leary, K.N., & Qudrat, A. (2012). A reexamination of sex differences in sexuality: New studies reveal old truths. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21, 135-139.

Schmitt, D.P. (2005). Sociosexuality from Argentina to Zimbabwe: A 48-nation study of sex, culture, and strategies of human mating. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28, 247-275.

Schmitt, D. P. (2007). Sexual strategies across sexual orientations: How personality traits and culture relate to sociosexuality among gays, lesbians, bisexuals, and heterosexuals. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 18, 183-214.

Schmitt, D.P. (2014). Evaluating evidence of mate preference adaptations: How do we really know what Homo sapiens sapiens really want? In Weekes-Shackelford, V.A., & Shackelford, T.K. (Eds.), Evolutionary perspectives on human sexual psychology and behavior (pp. 3-39). New York: Springer.

Schmitt, D.P. (2015). The evolution of culturally-variable sex differences: Men and women are not always different, but when they are…it appears not to result from patriarchy or sex role socialization. In Weekes-Shackelford, V.A., & Shackelford, T.K. (Eds.), The evolution of sexuality (pp. 221-256). New York: Springer.

Schmitt, D. P., & Pilcher, J. J. (2004). Evaluating evidence of psychological adaptation: How do we know one when we see one?. Psychological Science, 15, 643-649.

Schützwohl, A., Fuchs, A., McKibbin, W.F. & Shackelford, T. K. (2009). How

willing are you to accept sexual requests from slightly unattractive to

exceptionally attractive imagined requestors? Human Nature, 20, 282-

293. DOI: 10.1077/s13110-009-9067-3.

Selterman, D., Garcia, J. R., & Tsapelas, I. (2017). Motivations for Extradyadic Infidelity Revisited. The Journal of Sex Research, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1393494

Sizemore, K. M., & Olmstead, S. B. (2017). Willingness of Emerging Adults to Engage in Consensual Non-Monogamy: A Mixed-Methods Analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 1-16.

Surbey, M. K., & Conohan, C. D. (2000). Willingness to engage in casual sex. Human Nature, 11, 367-386.

Tappé, M., Bensman, L., Hayashi, K., & Hatfield, E. (2013). Gender differences in receptivity to sexual offers: A new research prototype. Interpersona, 7, 323.

Thompson, A. E., & Byers, E. S. (2017). Heterosexual young adults' interest, attitudes, and experiences related to mixed-gender, multi-person sex. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 813-822.

Thornhill, R., & Gangestad, S.W. (2008). The evolutionary biology of human female sexuality. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Tidwell, N. D., & Eastwick, P. W. (2013). Sex differences in succumbing to sexual temptations: A function of impulse or control? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, 1620-1633.

Weitbrecht, E. M., & Whitton, S. W. (2017). Expected, ideal, and actual relational outcomes of emerging adults'“hook ups”. Personal Relationships, 24, 902-916.

1 I invoke "denialism" in the sense of science denialism (Diethelm & McKee, 2009), particularly the tendency to cherry-pick and selectively report isolated findings among an overall consensus of evidence, and especially misrepresenting findings of specific papers. These two tendencies are clearly evident in this case. Science denialism also involves highlighting the flaws in only the weakest of an opponent's papers as a means of discrediting an entire field, using logical fallacies (i.e., red herrings, straw men, and false analogies), invoking conspiracy theories, and using fake experts.

2 I have been contacted by the first author of Baranowski, A.M., & Hecht, H. (2015). (A.M. Baranowski, personal communication, July, 24, 2017). It is confirmed that Rudman (2017) had not contacted the authors of Baranowski & Hecht (2015) to note the percentage of women (versus men) who agreed to potentially have sex with at least one stranger. It is perhaps possible Rudman had come to know the sex-specific data in some other way (e.g., at a conference or seminar), however the scientific citation provided by Rudman (2017) was to the original Baranowski & Hecht (2015) article. It is clear this reference in Rudman (2017) was inaccurate, and the very important actual test published in Baranowski & Hecht (2015) regarding the raw number of strangers that men and women agreed to have sex with was ignored (see above).