Artificial Intelligence

The Second Singularity

Human expertise and the rise of AI.

Posted December 3, 2019 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

The popular media loves stories about “the singularity” — the point at which computers get smarter than people, achieve consciousness, and take over.

The use of the term “singularity” in this way was coined by Vernor Vinge (1993), who asserted that “within 30 years, we will have the technological means to create superhuman intelligence. Shortly after, the human era will be ended.” This idea was popularized by Ray Kurzweil in his 2005 book, “The Singularity is Near.” Kurzweil explained how computers, especially Artificial Intelligence, combined with discoveries in genetics, nanotechnology, and robotics, will create a condition in which machine intelligence overtakes human intelligence. Kurzweil was not writing science fiction. He described the singularity as not only a real possibility but an inevitable one.

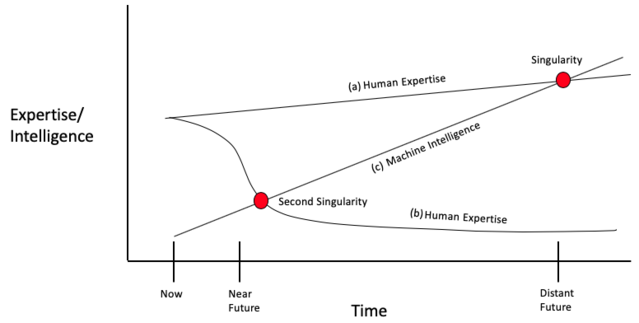

The second singularity describes what might happen when human expertise is not increasing very quickly and intelligent computers are rapidly getting more powerful: the point where the two curves intersect and the intelligent computer curve surpasses the human expertise curve.

Many researchers and philosophers have criticized Kurzweil and argued that the singularity is not near. They don’t think the singularity requires our urgent attention. I am in this skeptical camp. I don’t deny the progress in machine intelligence but I see evidence that the current rage for AI is over-sold. Projects such as IBM’s Watson that were going to sweep the field are now getting downplayed. Funders are tired of all the over-promising. Leading AI researchers are writing opinion pieces about how the field of deep learning is hitting a wall.

We have a better sense of the strengths and the limitations of Artificial Intelligence than we did when Kurzweil’s book appeared almost 15 years ago. So the notion of a singularity seems a bit less frightening these days.

What does worry me is a “second singularity.”

The second singularity is not just about computers getting more powerful, which they are, but the simultaneous reduction in expertise that we are seeing in many quarters. As organizations outsource decision making authority to machines, workers will have fewer opportunities to get smarter, which just encourages more outsourcing.

The second singularity is actually much closer to us in time than Kurzweil’s original notion of a singularity. It is a second singularity in deference to Kurzweil’s analysis, rather than for chronological reasons.

Now, the reduction of expertise isn’t happening across the board. There is also a growing set of skills for which more people become experts, such as programmers, network administrators, and cybersecurity watchdogs. The number of doctors in the US has risen from 813,000 in 2000 to 1,085,000 in 2015.

The Congressional Research Service reports that scientists and engineers grew from 6,187,760 in 2012 to 6,934,800 in 2016

And the American Bar Association reports that the number of practicing lawyers has increased by 15% over the past ten years, even as online legal services have grown:

So in a number of ways expertise is increasing -- different types of expertise are needed these days, in domains that didn't exist 50 years ago.

Nevertheless, there are a number of areas in which expertise is still quite valuable but is getting lost, such as many manufacturing specialties and in health care. In aviation, both for flying and for maintenance. In many petrochemical plants managers are looking for ways to automate operations. Similarly, directors of Child Protective Services agencies are exploring tactics to automate the work of intake specialists and caseworkers.

Expertise is not a permanent quality. It can erode within any organization or sector within a few generations, where “generations” is measured in 5-10 year chunks. Worker turnover, reduced recruitment standards, cuts in training budgets, and dangerous retreats to so-called “just-in-time” training, all can take a toll. And then you have a ratcheting effect as the reduced expertise just leads to greater reliance on mechanical decision making which discourages any more investment in promoting workers’ intuitive capabilities. It goes downhill from there.

It goes downhill quickly. Some might see an analogy to climate change arguments that by the time we decide there’s really a problem it may be too late to reverse the damage. We may only discover the value of expertise after it has been lost.

For practical reasons, organizations want to reduce their reliance on experts. It takes time and funding to develop experts so it is cheaper to rely on algorithms or machines.

Or at least it seems cheaper if you don’t factor in all the effort of building the algorithms or designing the AI system, and don’t worry about the effort of modifying these to meet changing conditions. And if you don’t worry about brittle systems that break down when stressed by unexpected conditions or sensor failures or things like that. (Think of the Boeing 737 MAX crashes. In the past, we have relied on experienced operators to detect that the machines aren’t appropriately aligned, and to intervene, but we lose that safeguard if we do away with the experienced operators. And if you don’t worry about malicious actors eager to exploit vulnerabilities in the AI systems. Even if the algorithms and AI systems don’t quite perform as well as humans, at least they are more reliable (at least when conditions are stable), and in our Lean Six Sigma culture reliability is very highly prized.

Making matters worse is a “war” on expertise. My colleagues Ben Shneiderman and Robert Hoffman helped me with this essay, and together we described how this war on expertise (Klein et al., 2017) is being waged by five different communities that are all claiming that expertise is overstated, or unreliable, or even non-existent. The message from these communities is that we can’t rely on experts and that we should rely on other means for making decisions — algorithms or checklists or artificial intelligence or communities of practice or codified best practices.

My colleagues and I explained the fallacies that are driving this war on expertise. We showed how none of the arguments stands up to scrutiny. The daily miracles of surgeons, teachers, pilots, control room specialists, and even programmers, should serve as a sufficient rebuttal to this war on expertise.

Nevertheless, the take-home message from these five communities is just what corporations and other large organizations want to hear — it provides them with an excuse to replace human expertise with machine expertise.

Therefore, in selected domains, we are seeing organizations actively reducing their stock of expertise in favor of automated or checklisted decision making. That’s what I am calling the Second Singularity. Once the Second Singularity is approached, I don’t see how anyone can go back. The expertise is permanently lost. The tacit knowledge, the perceptual skills, the mental models, are gone forever.

The figure below shows the two singularities. The top curve, (a) shows a normal rate of increase of human expertise. Curve (b) shows the reduction in expertise that we should be worried about. And curve (c) shows the rise in machine intelligence. Kurzweil’s singularity is the intersection of curves (a) and (c) in the distant future, reflecting the faster gains in machine intelligence than human expertise. But in areas where human expertise is allowed to wither away, we see the Second Singularity not much past the near future. That’s where curves (b) and (c) intersect. In some cases, the Second Singularity has already occurred.

I am not worried about domains in which it does make sense to build machines that can reliably conduct some of the tasks that people currently perform. If I contemplate a future in which my self-driving car can reliably parallel park itself without my intervention, and my parallel parking skills erode, I’m for it. In fact, we seem to be already there for a growing number of automobile models. Therefore, we shouldn’t worry about preserving expertise merely out of nostalgia. No one except a few archeologists knows how to chip rocks in order to make flint knives anymore, and our society is none the worse.

What we should worry about is the set of domains where the expertise being eroded is valuable and essential — for any machine, there will always be off-nominal situations where the machine will be brittle and where skilled operators will be necessary to align the machine’s model of the world with the actual world (see Woods & Sarter, 2000). We should worry about domains that are trading long-term security for short-term convenience and economics. I think for these domains, for these organizations, the Second Singularity is already too close and getting closer.

So what can we do?

First, we can try to raise awareness of the Second Singularity and the risks it poses.

Second, we can try to promote a greater appreciation for expertise and the strengths it provides, such as relying on frontier thinking to handle novel conditions, and using social engagement to enlist help from others, and accepting responsibility for decisions.

Third, we can advocate for governments and corporations to reduce their support for building smarter machines and instead to support ways to build machines that make us smarter.

Fourth, we can encourage a practical science of expertise, out of the laboratory and into the workplace. This activity would treat expertise as an essential and fragile commodity and would construct tactics to strengthen it.

The Second Singularity is not inevitable. It would be the product of our own making. We don’t have to let it happen.

References

Klein, G., Shneiderman, B., & Hoffman, R.R. (2017). Why expertise matters: A response to the challenges. IEEE: Intelligent Systems, 32(6): 67-73.

Kurzweil, R. (2005). The singularity is near: When humans transcend biology. Viking Press.

Vinge, V. (1993). The coming technological singularity: How to survive in the post-human era. VISION-21 Symposium, March 30-31.

Woods, D.D., & and Sarter, N. (2000). “Learning from automation surprises and going sour accidents.” In N. Sarter & R. Amalberti (Eds.), Cognitive Engineering in the Aviation Domain, Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, N.J., pp. 327–353.