Psychopharmacology

Is Wanting to Change Enough?

Designing for sustained adherence.

Posted September 20, 2019 Reviewed by Devon Frye

This essay was written by Devorah Klein, Marimo Consulting LLC, and Gretchen Wustrack, Curiosity Atlas. It is a response to questions I posed to them about what it takes to get people to change how they act and to sustain those changes.

We all know how hard it can be to make a tough change—medication adherence and behavior change, in particular, are notoriously challenging. It's easy to wonder if it is even possible.

In this essay, we take a design thinking perspective and share tools with tactical implications for real adherence problems. (We define adherence as taking prescribed actions to gain the maximum benefit.)

This essay is about designing ways for patients to adhere to a medical regimen, but the lessons will resonate beyond healthcare to any situation calling for people to make lasting changes to their behavior.

Medication adherence is important for many reasons. An estimated 10 percent of all hospital admissions result from patients who fail to use their medications properly. In the U.S., the cost of improper use of prescribed medications is over $100 billion per year (Viswanathan et al. 2012)

What can be done to help patients take their prescribed medications properly? We began studying this problem over a decade ago when we were both working at IDEO, the global design consultancy; we acknowledge the support and encouragement we received from the IDEO organization. We studied a wide range of conditions requiring different adherence tactics, ranging from HIV medications to weight loss programs to multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and erectile dysfunction (Klein, Wustrack, & Schwartz, 2006). We’ve also used these tools far beyond healthcare, in behavior changes in financial services, social engagement, and environmental stewardship.

We see medication adherence as depending on three dimensions:

- the elements acting on adherence

- the nature of the adherence journey for each patient

- the adherence loop

The Elements of Adherence

We have identified four elements that act on adherence: the individual (who they are, what has been their experience, what are their goals); the condition and how it affects the patient’s life; the therapy (the regimen, the resources required, the duration); and the adherence network of friends, family, professionals, and institutions. These elements vary considerably for different patients and conditions and understanding that context is very helpful.

The Adherence Journey

The adherence journey consists of three phases: Preparation, initiation, and maintenance.

The preparation phase includes the patient’s understanding of the condition and its consequences (especially the consequences if untreated) and assessment of different treatment options, along with the type of commitment needed for each option. If the patient is motivated to begin a course of treatment, she or he enters the initiation phase, which can include practical considerations such as insurance coverage and travel schedules to see specialists but also logistical and practical issues, such as having a reliable supply of medications and the challenges of integrating the regimen into daily activities and into life-cycle events.

Once the patient gets to a steady state of following a regimen, he or she enters the maintenance phase, which depends on reliably following the established routines and also getting back on board after the inevitable adherence failures. The maintenance phase includes wrestling with side effects and relapses. All three of these phases are marked by ups and downs as the patient’s enthusiasm and commitment waxes and wanes.

The four elements play out differently for each patient and across the three phases.

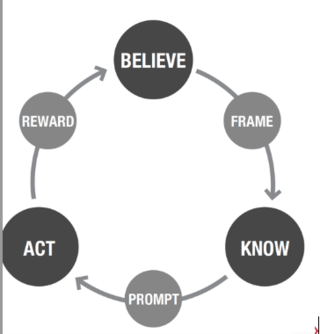

The Adherence Loop

- This loop has six components for the patient: Do you believe the therapy will work?

- Can you frame how the therapy (or proposed change) will help?

- Do you know how to use it?

- Can you prompt action when needed?

- Do you have the resources to act at the different phases of the therapy journey?

- Is there a meaningful reward with feedback to reinforce action and strengthen belief?

The believe component includes beliefs that you truly do have the condition, that you really want to change (as opposed to someone else telling you to change), that the therapy will help, and that you can be successful.

These beliefs are the core of the mental model that will underpin all that follows.

The frame component is how people build mental models or frameworks of how the change is going to help. While most people have some sort of mental model, it may or may not be accurate. The more accurate and complete the mental model, the more powerful a tool it is (H. A. Klein, & Lippa, 2012). Particularly when people are under stress or need to make trade-offs in optimal change, the validity of the mental model can help people make those trade-offs most optimally.

The know component covers the rules and procedures for following the regimen. It also includes knowledge of what to expect at different phases of the journey. Support here includes judging whether the patient is getting overloaded by information, or determining that patients aren’t getting the information they need or are getting misinformation.

However, knowing what to do is not enough—the patient will need cues and prompts to stay on course: to take doses at the right time. These prompts should fit comfortably within the patient’s lifestyle schedules.

The act component refers to the resources the patient will need: physical, cognitive, emotional, social, and financial. Shortfalls in these resources will diminish the chances of successful adherence. Is the therapy physically hard to take—or is it socially hard because it is embarrassing or awkward?

On top of all this, patients should ideally be getting feedback to close the loop and reward and reinforce the beliefs and the motivations; ideally, this feedback would show immediate rather than delayed effects. Patients should get feedback on both each individual action and also the impact of the repeated actions over time. And the team should be alert to side effects.

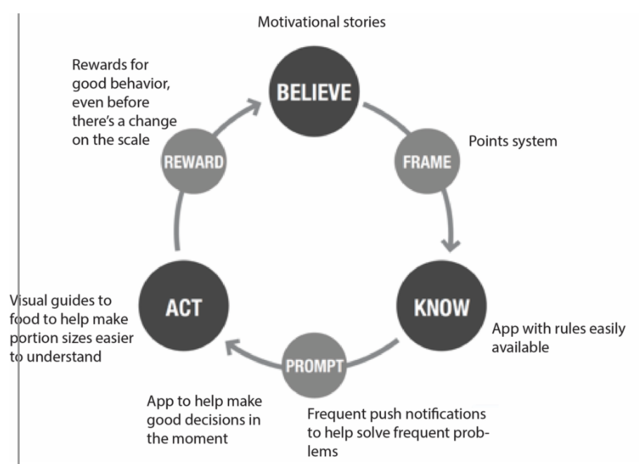

Weight Watchers is an example of a very successful weight-loss program. It is useful to use the adherence loop to make sense of all the aspects of Weight Watchers.

The six dimensions of adherence that we have described should enable healthcare personnel as well as patients to increase adherence success rates. In turn, that should give patients more confidence in the therapies they are using, increase revenues for businesses involved in supplying therapy materials, reduce costs overall for the healthcare system, and improve patient outcomes.

The goals for these tools are both descriptive, to help understand which parts of the loop are broken for a given adherence situation, but also generative. They were created to help design new interventions and suggest design principles:

BELIEVE: Get Personal

Engage at life stage transitions when priorities and personal motivators change.

FRAME: Offer Meaningful Choice

Help people make tradeoffs to find a lifestyle fit.

KNOW: Stage Information

Provide the right information at the right time to ensure relevance and ease of comprehension.

PROMPT: Piggyback on Patterns

Design systems that dovetail with people’s existing daily, weekly and monthly routines.

ACT: Tip the Scales

Make the positive behavior more convenient, fun, or attractive than the negative behavior.

REWARD: Mind the Gap

Provide immediate and tangible feedback, encouragement or rewards for the new behavior.

Summary

We think the six dimensions will help both patients and providers identify and focus on the key adherence problems to solve. They should help providers better understand the role of individual differences and do a better job of finding analogous solutions in other domains. In addition, the six dimensions should help patients and providers better understand therapy or program profiles, identify and take advantage of support networks, and create solutions that work in everyday life.

Thus, the loop can help people determine the key adherence challenges to overcome. But the loop can be much more than that. It can also be a tool to help healthcare providers design solutions by pointing to the ways that patients are struggling and guiding the search for solutions. The output of the loop—a set of thoughtful designs focused on the biggest needs of the patients—has changed the way we approach adherence challenges. We hope it will help you as well.

References

Klein, D.E., Wustrack, G., & Schwartz, A. (2006). Medication adherence: Many conditions, a common problem. Proc. 50thAnnual Meeting of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, San Francisco, CA. 1088-1092.

Klein, H.G.A.& Lippa, K. (2012). Assuming control after system failure: Type II diabetes self-management. Cognition, Technology & Work. 14. 10.1007/s10111-011-0206-3.

Viswanathan M, Golin CE, Jones CD, Ashok M, Blalock SJ, Wines RC, Coker-Schwimmer EJ, Rosen DL, Sista P, Lohr KN. (2012). Interventions to Improve Adherence to Self-administered Medications for Chronic Diseases in the United States: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med., 157:785–795.