Gender

A New Study Blows Up Old Ideas About Girls and Boys

Is gender a mere tool of the patriarchy? Or is it hardwired prior to birth?

Posted March 27, 2019 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

If there are superstar scholars, Berkeley professor Judith Butler is a superstar. She is best known for pioneering the idea that “male” and “female” are merely social constructs. She writes that “because gender is not a fact, the various acts of gender creates the idea of gender, and without those acts, there would be no gender at all.” For this insight, she has been rewarded with an avalanche of scholarly honors and prizes, including the Mellon Prize, which carries with it a $1.5 million cash award. (By comparison, the Nobel Prize gets you just $1.1 million.)

Butler is a professor of comparative literature, not a neuroscientist, but her ideas about gender have become widely accepted worldwide in the nearly 30 years since the publication of her book Gender Trouble. In 2017, Cordelia Fine, professor of historical and philosophical studies at the University of Melbourne, published a book titled Testosterone Rex: Unmaking the myths of our gendered minds. Following Butler, Fine asserted that any claims that women and men differ significantly in brain or behavior are simply myths perpetuated by the heteronormative patriarchy. Fine’s book promptly received the Royal Society’s prestigious prize for best science book of the year.

The worldview promulgated by Butler, Fine, and their followers now constrains what neuroscientists are allowed to say in public. A professor of neurophysiology at Lund University in Sweden recently told undergraduates that the categories of female and male are, to some degree, biological realities rather than social constructs and that some differences in behavior between women and men might, therefore, have a biological basis. He was promptly denounced by students who claimed that his remarks were “anti-feminist.” The dean of the medical school duly launched an investigation.

I have debated this topic with followers of Butler and Fine in various settings. When I share with them research showing, for example, robust female/male differences in the trajectories of brain development, the most common response is sheer ignorance of the finding in question. It is unusual for a devotee of Butler to say, “Yes, I am aware of that research. However, I consider that research invalid because of XYZ.” Instead, they more often claim that the research must be meaningless because it involved children or adults. Children and adults have spent years being subject to the heteronormative patriarchy. Parents interact differently with girls and boys from the moment of birth, these critics (correctly) observe. So any study of adults, or even of children, is hopelessly marred by the sexist societies in which we all live.

Fair enough. For the sake of argument, let's grant that point. So let’s study humans before birth. In recent years, there have been fascinating studies in which neuroscientists have studied the brains of babies in their mothers’ wombs. One remarkable study was a collaboration among neuroscientists at Yale, Johns Hopkins, and the National Institute of Mental Health, alongside neuroscientists from Germany, the UK, Croatia, and Portugal—more than 20 researchers in all. These investigators looked at how individual genes are transcribed in the human brain from the prenatal period through infancy, childhood, adolescence, and throughout adulthood. They found that the biggest female/male difference in gene transcription in the human brain, for many genes, is in the prenatal period. (See for example their graph of the transcription of the IGF2 gene, a gene known to be involved in cognition: male/female differences in transcription for IGF2 are huge in the prenatal period, and nonexistent among adults.) Again, I have not yet found an advocate of the Butler/Fine school who is even aware of this research, let alone responded to it. If the Butler/Fine theory was correct — if gendered differences in brain and behavior are primarily a social construct, and not hardwired — then we ought to see zero differences between the female brain and the male brain in the prenatal period, but large differences between adults, who after all have had the misfortune of living all their lives in a heteronormative patriarchy. But the reality is just the opposite: Female/male differences are generally largest in the prenatal period, and those differences diminish with age, often dwindling to zero among adults.

Now we have another, even more striking study of the human brain prior to birth. In this study, American researchers managed to do MRI scans of pregnant mothers in the second and third trimesters, with sufficient resolution to image the brains of the babies inside the uterus. They found dramatic differences between female and male fetuses. For example, female fetuses demonstrated significant changes in connectivity between subcortical and cortical structures in the brain, as a function of gestational age. This pattern “was almost completely non-existent in male fetuses”. They note that others have found, for example, that female infants have significantly greater brain volume in the prefrontal cortex compared with males. They conclude that “It seems likely that these volumetric differences [found after birth] are mirrored by [the] differences observed in the present study.”

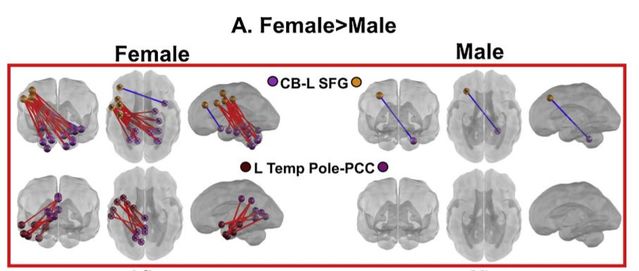

Some of the sex differences in the new study are truly amazing. See for example the image above (figure 4A from their paper) showing differences in female connections between the left cerebellum (CB) and the left superior frontal gyrus (SFG), and between the left temporal pole and the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) compared with males. Remember, these are fetuses in utero! In other brain areas, the differences were not so striking. A reasonable next question might be: Why do these brain areas, and not others, show such dramatic female/male differences? Another reasonable question would be: Why haven’t the mainstream media in the United States covered this new research?

References

M.D. Wheelock, J.L. Hect, E. Hernandez-Andrade, and colleagues (April 2019). Sex differences in functional connectivity during fetal brain development. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, in press.