Stress

Why Do We Say Everything Is Fine When It Isn’t?

How to avoid the pressure to be positive all the time and learn to open up.

Posted September 21, 2021 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Struggling and overcoming adversity often leads to significant personal growth.

- Identifying emotions and sharing feelings can help people recover from traumatic or challenging experiences.

- Acknowledging real-life stressors isn’t the same as complaining.

School is back in session and my 9-year-old is off to a rocky start.

I’m maxed out between work deadlines and family obligations. Feeling exhausted. Overwhelmed. Anxious.

But when I ran into a neighborhood mom on the street, I presented only the positive.

“How are you doing?” she asked.

“Good,” I told her. “Marty is excited to be back in school and work is going well.”

Would she want to know that I spent the last hour in the corner of my closet crying? That I felt alone?

Maybe I wanted to appear strong. In control. Like I’ve got this. What’s so hard about raising a child? Writing a book proposal?

I fantasize that other moms have it easy.

I know they don’t.

When I read Venus Williams’ guest essay about mental health in The New York Times, I thought a lot about the strength it takes to acknowledge what others might perceive as weak. “Admitting feeling vulnerable is no joke,” she writes. “It isn’t easy to … confide in people about having emotional struggles.”

Why does it feel like we aren’t supposed to struggle?

I feel it acutely in my neighborhood of achievement-oriented parenting and pressure to excel. The word on our street is “great.”

At a recent gathering, I spoke to a tired-looking dad with two young kids and a sick baby and asked, “How are you?”

“I’m great,” he said, forcing a smile.

No one wants to complain. But is being emotionally honest the same as useless grumbling?

When I talk to neighborhood parents, it feels like we’re all hyper-focused on the good news. Avoiding anything that could be perceived as negative. G-d forbid we reveal imperfections.

The value of opening up about real-life stress

Psychotherapist and best-selling author Amy Morin said many parents don’t want to share everyday struggles. “There’s a lot of pressure to be positive,” she said.

Morin, who wrote 13 Things Mentally Strong People Don’t Do, explained there’s a big difference between venting, which can keep people in a heightened state of frustration, and sharing the reality of a tough situation. “Talking about how you feel about the problem as opposed to just complaining can be helpful,” she said. “There is value in being heard.”

When someone feels understood, they know they aren’t alone. That, she explained, can help people cope with stress and anxiety.

Moving from struggle to strength

It took me a long time to understand that.

Before I became a mom, I spent a long time struggling and keeping it to myself. Nothing came easy. I made many mistakes. Like when I was 30 and stayed in a three-year relationship with a guy who didn’t believe in me.

Instead of presenting the reality to friends, I told them things were “great.” They were far from it.

As I’ve written in earlier posts, he called off our wedding three days before.

Finding my way through the aftermath of that experience was like diving through wave after wave of huge emotion. It left me exhausted. But instead of drowning, I discovered an inner strength I never knew I had.

Maybe that’s why I became a war reporter.

The key to getting through tough times is talking about it

Psychologist Dr. Don Meichenbaum studies trauma and resilience. His research shows that 75% of people who suffer a trauma go on to experience significant personal growth. “The question is not that you get stressed or anxious,” he explained. “It’s what you do with these feelings.”

The key to recovering, he said, is sharing your feelings with others.

Communicating. Being vulnerable.

That’s exactly what I learned from a group of women during my first trip to a war zone.

How our stories connect us

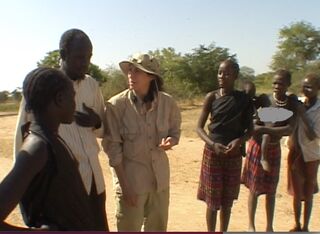

In December 2001, I traveled to rebel-held villages in Southern Sudan.

During a 20-year civil war between an Arab government in the north and Black African tribes fighting for independence in the south, northern militias raided southern villages, kidnapping women and abusing them in ways that are unimaginable.

Queth Atheon told me, “I was raped by five men in a line, one by one.”

Abu Abak was 14 when she was taken. “They tied my hands to a horse and I was raped by the militia on the way to the north,” she said.

Ayut Dut Ding touched her breast as she spoke to me. It was full of milk. In the rush of escaping, she was separated from her baby. She vowed to search for her child and to keep living in the hopes of one day reuniting.

They experienced the worst of what one human can do to another. What shocked me weren’t the details of their trauma but that after talking about it, they felt better.

They survived and re-integrated into their villages, raising families. Their suffering and struggle did not define them. Their resilience, recovery, and strength did.

They taught me that words are powerful. To communicate is to connect. To support each other—with hope, determination, and understanding.

Showing vulnerability isn’t shameful

Over the next decade, I covered conflicts, hurricanes, wars and school shootings.

Every place I went, I met resilient people who shared their stories and experiences without shame. Without judgment. With honesty and guts.

I always asked people, “Do you want to talk about your experience?”

I can’t remember anyone saying no.

Psychologists say there’s a reason. It’s a process called “affect labeling.” According to the research in this study, when people put feelings into words, they are better able to regulate their emotions. Over time, if you label feelings and talk about them, you can become less stressed out about things that upset you.

Looking back, my wedding that wasn’t seemed like a glitch compared to what people living through tragedy endured. But their emotional honesty inspired me to think differently about the strength it takes to share details of a traumatic or difficult experience, regardless of the magnitude. And if people can find the courage to share their pain and work through their trauma, can’t we at least tell our friends that it hasn’t been a good day?

A focus on emotional vocabulary

When I had Marty, I understood the value in helping him build his emotional vocabulary. When he was 4, he had a mood meter hanging in his room with pictures of people showing different emotions. Every night we talked about the day’s easy moments along with the tougher ones.

He’s become really good at identifying how he feels and sharing it.

But as a mom, I’ve become more guarded. Is it vanity? Insecurity?

I could blame it on my neighborhood of competitive parenting, but I know it’s an inside job. Thankfully, my 9-year-old is reminding me how to get the work done.

Marty knows what I’m continuously learning

Marty was home from school this week, sick with a virus (not COVID). Life is complicated. Messy. Frustrating.

“What’s wrong mom?” Marty asked.

“Nothing. I’m just tired,” I said.

“No, I can tell you’re sad,” he said as he sat down next to me. “Let’s talk about it. You’ll feel better.”

Later that afternoon, Marty talked to a friend on FaceTime. He didn’t fight an urge to present the positive.

“How is school going?” the boy asked.

“It’s been tough,” Marty said. “The first day was pretty bad. But the second day was better. I didn’t go the third. The fourth was great. But now I’m sick.”

“Sometimes I don’t like school either,” his friend said. “It’s hard.”

“Thank you for telling me that,” Marty replied. “Should we play Roblox or Minecraft?” the boy asked.

Sum it up

It takes strength to talk about feelings and experiences that could be perceived as negative or weak. But research shows that it’s healthier to communicate and share our fears and frustrations than to keep them bottled up inside.

3 tips for sharing a struggle

1. Find trusted friends: Choose to share your feelings with friends who can support you. Psychotherapist Amy Morin suggests starting small. “You don't have to sit down and explain all the horror stories of your life at once,” she said. It might make sense to start with sharing some stress from your day.

2. Work with a therapist: Think of a therapist as a personal trainer. They can help you make sense of your feelings by talking about your emotions. Over time, you build resilience and inner strength. They are like muscles in the brain that enable people to bounce back from challenging situations.

3. Write it out: One way to process complicated emotions is to write them down. Psychologists call this “therapeutic journaling.” Dr. Shilagh Mirgain says that “putting things on paper [helps] people make better sense of them.” This can be a first step in sharing an experience and reducing bottled-up stress.