A recent year-end Wired article touted, “We’ve Got the Screen Time Debate All Wrong. Let’s Fix it.” They got it right! Yes, by and large, more screen time could be problematic or create Problematic Internet Usage (PIU) or smartphone addiction or whatever name you prefer but it is not such a simple equation where more screen time = more problems. In our research, we have been monitoring screen time with young adult college students (average age 25 and more akin to young adults than to young college students) since 2016 with three samples of participants that allow for model testing. We have also started to do the same with high school students. [NOTE: for more information on these studies see my most recent PT blog posts: Will Apple and Google’s New Apps Change Additive Phone Use? and Curbing Our Tech Obsession]

The Wired article quotes several studies, each looking at the impact of “screen time” on problems including depression, cortical thinning, and general well-being and concludes that,

“If there's one thing that gets lost most consistently in the conversation over alluring technology, it's that our devices contain multitudes. Time spent playing Fortnite ≠ time spent socializing on Snapchat ≠ time spent responding to your colleague's Slack messages.”

In our work we have been attempting to get a handle on what aspects of screen time are problematic in the realm of psychological well being, sleep and, most recently, academic performance (because, after all, our participants are college students and academic performance is a handy metric to pursue). We know from the literature that poor executive functioning (EF), boredom and what we call technological anxiety but others label as nomophobia, all contribute to poorer academic performance. More importantly, however, we have examined how these issues impact screen time in various ways, which, in turn, impact academic performance. In a recent yet-to-be-published study with more than 350 participants, we started with a model including self-reported screen use in 11 areas, app-reported total daily screen time, attention while studying, multitasking preference, social media usage and what we call “classroom digital metacognition.” The latter refers to knowing what to do with your phone during class and when it is and is not appropriate to use it in class. Social media usage combined the self-reported use of the top 12 social media sites.

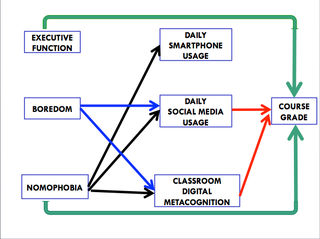

In line with Wired’s message, in our preliminary model testing, we found some clear impacts of screen time that mediated the impact of our three main predictors of EF, boredom, and nomophobia. While EF and nomophobia both directly predicted academic performance (as seen in the literature), boredom and nomophobia predicted two of the screen time variables which then predicted poor academic performance: social media usage and metacognition. The picture here shows the tentative model pending peer review.

What does this all mean? These results suggest that it is not simply the amount of screen time that is the problem but it is choices made about when to use screen time and where to use that time. In short, it is all about communication and metacognition. This confirms what Common Sense Media found in their recent cross-sectional study of teenage screen use. In 2012, 35% of teens used social media more once a day; six years later, in 2018, that jumped to 70% of teens using social media more than once a day. In our studies, the typical young adult had an active presence on nearly six social media sites which would, of course, require constant checking.

No wonder boredom and nomophobia promote more social media usage. When you are obligated to keep up with all of those social media sites—plus incoming texts, phone calls, emails and other forms of communication—then any time you have a moment your brain will drive you to check in with your virtual world of connections. And add to that the fact that poor metacognition means your brain can’t help itself and you have a perfect storm of screen time use promoting problems.

I was excited when Apple introduced their Screen Time app to provide general and specific information about your personal smartphone usage including how much time you actually spend doing various activities during your screen time. Google’s Digital Wellbeing does the same although at this writing it is only available on Pixel phones. As a scientist, I was dismayed when I discovered that there is no way to download those data to provide researchers a detailed picture of your daily or weekly screen time use. When I emailed Apple’s PR department representatives who released the Screen Time app press release I was told that those data were, “personal” and, thus, not downloadable. Other apps such as Moment do allow you to download app usage data but shouldn’t Apple follow suit and help researchers learn precisely what types of screen time promote positive or negative well-being? As a scientist who has been avidly researching these questions for decades, it seems that Apple holds the key to data that will help scientists pin down the reasons why certain types of screen use lead to certain types of problems. One can only hope that they will come to the same conclusion and make those data available for easy download. Until then other tools such as Moment will provide the needed research data.