Nothing stirs our imagination like the inability to imagine the past or to envision the future. We are enchanted and haunted by stories of memory loss, distortion, and retrieval. Some experiences are commonplace, like the “tip-of-the-tongue” experience of not being able locate the right detail or word. Occurrences of false memory and imagination inflation remind us that remembering is as much about the present as it is about the past. Other forms of memory loss are more debilitating, such as those related to traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s disease, and other types of neural breakdown and dementia. Much can be made of the science of memory and we have high hopes for improvements in how memory disorders can be understood and treated.

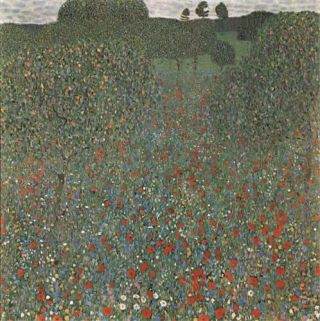

Yet we might also wisely resist what Gary Greenberg has called, “the tyranny of the brain”—a seemingly futile effort among some neuroscientists to reduce mental life to molecular biology. Memory—as a function of the brain—cannot be reduced to individual molecules any more than Satie’s Gymnopédies can be best understood as fragments of pitch and frequency. We have always needed complementary ways to account for memory and its gaps, such as the humane, lyrical storytelling of Oliver Sacks, whom the New York Times once called, “a kind of poet laureate of contemporary medicine.” Memory’s underpinnings have long been explored by artists and writers—from Klimt to Proust. Some contemporary works also deserve our attention.

In her forthcoming collection, The Book of Memory Gaps (Blue Rider Press), illustrator Cecilia Ruiz offers a darkly humorous but warmhearted account of various memory errors and disorders. These are one-to-two-sentence, miniature stories, each with an accompanying illustration. We meet Polina, a young dancer who, after a fall, believed that “every night was the opening night.” We meet Igor, beset by the false memory of a nonexistent fight. Then there is Simon, a priest whose memory was so vast that he was burdened by every confession he had ever heard—to the point of believing he had committed everyone’s “borrowed sins” (one thinks of A.R. Luria’s classic depiction of patient S., a man also burdened with remembering too much). Here we have examples of anterograde amnesia, agnosia, blocking, false memories, and everyday absentmindedness. The brief captions imply a much more complex narrative but give us just enough information to fill in the blanks. The illustrations—lovely and quirky—manage to both depict a snapshot in time while also conveying memory’s ephemeral, transient nature. Ruiz is neither cynical nor condescending in these vignettes, and the tone of the book is kindhearted and nicely captured in its epigraph: “We are the things we don’t remember, the blank spaces, the forgotten words.”

Ruiz’s book reminded me of Anthony Doerr’s collection of short stories, Memory Wall. In six remarkable stories, Doerr explores the fragile, perishable, and sometimes cruel nature of memory. We have stories of memory’s oppression—a man overcome with the memories of his wife’s betrayal; an elderly epileptic who has seizure-induced memories of living in a Jewish orphanage during the Nazi occupation. In the title story, a white South African widow suffers from dementia and requires the use of a fictionalized device that records and stores her memories. This device prevents the “cruel erasure” and mental corrosion of her dementia. She maintains a “memory wall” that is a kind of immersive photo album—she can plug into a device and transport herself to a previous time. Her physician, Dr. Amnesty, tells her at one point: “Memory builds itself without any clean or objective logic: a dot here, another dot here, and plenty of dark spaces in between. What we know is always evolving, always subdividing. Remember a memory often enough and you can create a new memory, the memory of remembering.” Memory Wall is a story of how memories are stored, lost, and in some cases found. In the end, it is a mystery in search of buried treasure.

A central theme of Doerr’s book is expressed in the epigraph of the book by the Surrealist filmmaker Luis Buñuel: “You have to begin to lose your memory, if only in bits and pieces, to realize that memory is what makes our lives.” And our memories are bound to fade as we age, if for no other reason. One of the benefits of psychotherapy, for many people, is learning to forget aspects of one’s life that are debilitating, paralyzing, irrational, or simply unhelpful. Memories, as symtoms, can be worked through in a way that allows for a more adaptive form of remembering and forgetting. The psychoanalyst Hans Loewald, commenting on the negative impact of traumatic memories, once said that psychotherapy can help, “turn ghosts into ancestors.” In the end, as memories fade, our identity is shaped as much by what we remember as what we forget.

© 2015, Bruce C. Poulsen, All Rights Reserved.