A blush is no language; only a dubious flag-signal which may mean either of two contradictories.

A blush is no language; only a dubious flag-signal which may mean either of two contradictories.

- George Eliot

In the Ridly Scott film, Blade Runner (based on Philip K. Dick's novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep), genetically engineered robots–called replicants–have become indistinguishable from humans in an imagined, dystopian future. The replicants have escaped from other space colonies to try to expand their life span by living on Earth. The replicants must be retired (killed) and so "blade runners"–special police officers–are employed to track down possible replicants and interrogate them to determine whether they are human or not. The Voight-Kampff machine is a kind of advanced lie detector used by the blade runners to determine whether an individual is a replicant or a human. In response to emotionally provocative questions, it measures involuntary physiological functions including respiration, heart rate, eye movements, and the "blush response." In this post-apocalyptic world of organic robots intermingling with human beings, these fictional measures of autonomic nervous system functioning are used to assess empathy–the distinguishing feature. If they blush, they are not likely to be replicants but to be involuntarily empathic human beings.

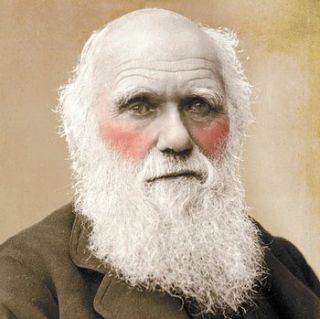

Charles Darwin called blushing "the most peculiar and most human of all expressions" and was among the first to draw attention to blushing as a medical or neurophysiological phenomenon. In one of his lesser known works called Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, published after Descent of Man, Darwin saw blushing and similar anxious behaviors as representing an "odd state of mind" that likely have adaptive roots. He stated that blushing makes a person "suffer and the beholder uncomfortable, without being of the least service to either of them." So what exactly is this most peculiar and most human of all expressions? What do we communicate when we blush? Is there an upside to blushing? Finally, what, if anything, do we learn about ourselves by understanding the phenomenon of blushing?

Most of us readily recognize when we blush. There is a reddening of the cheeks and forehead, which can extend to the ears, neck, and upper chest–the so-called "blush region." Awareness that we are blushing only amplifies the response. We experience a heightened suggestibility for blushing–when accused of blushing when we are not, we may then blush. Mark Leary and his colleagues have distinguished between the classic blush–a sudden reddening of the face–which might occur in response to being praised or simply being singled out suddenly, and the creeping blush, such as what might occur when someone is giving a lecture or being interviewed for a job. The creeping blush tends to progress more slowly and may involve a larger part of the blush region. Whatever the type, blushing involves the autonomic nervous system–specifically, the sympathetic nervous system–and is involuntary and uncontrollable.

Does blushing serve a purpose, fulfill some kind of function, or is it something we would just as soon do without? Leary and colleagues have suggested that a blush may be the result of unwanted social attention. They have proposed that blushing occurs as a consequence of threats to public identity, openness to scrutiny, praise and positive attention, and accusations of blushing. Blushing is thus viewed as an inevitable, hard-wired response to situations where we are scrutinized, attended to, and complimented. The scrutiny can also come from ourselves and we are uniquely capable of inducing a blush by resisting it.

To take a more psychological view, when we blush, we may betray aspects of our self that we may otherwise wish to conceal. A flushed reaction to a compliment may at first glance suggest modesty, but could more fundamentally reveal a sense of being undeserving or an expectation of imminent failure. When being singled out in a group, our rosy cheeks may signal–not only our social discomfort–but a sense that we will be found out, that something unacceptable about us may be discovered. An upside to blushing is that, like dreams, our blushes may offer us glimpses into some of our most basic fears and wishes.

Perhaps the blush is a signal (as hinted at by George Eliot) and serves a communicative function. This theory is supported by the observation that we don’t seem to be able to blush alone. We seem to blush in the company of others. When we blush at innuendo we acknowledge a shared awareness of social norms and communicate this sympathetically, with our nervous system. When someone talks about sex, we may blush to signal excitement, disgust, or embarrassment–which allows us to maintain verbal politeness and decency. Over the course of our evolution, such signaling may have served adaptive functions in reducing interpersonal conflict and maintaining appeasement.

Blushing is a way of expressing contradictory emotions with interpersonal efficiency. In this way, blushing is all about keeping the peace and maintaining the social status quo. We are able to express our wishes without foreclosing upon social alliances and expectations. We can feel alarmed and be socially attentive at the same time. We can receive praise while also maintaining solidarity. To blush is to multitask contradictory impulses. The ability to blush is the ability to show empathy.

© 2012 Bruce C. Poulsen, All Rights Reserved