Neuroscience

K-1 Literacy Milestones Based on 5 Science-Based Facts

Find out whether your child is meeting typical grade-level literacy milestones.

Posted June 27, 2022 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- Children should learn to read by the end of first grade.

- The reading brain architecture is developed by explicit and systematic teaching in four phases supported by neuroscience and psychology.

- Parents can check if their child is meeting typical grade-level reading, writing, and spelling milestones for kindergarten and first grade.

Do you know if your kindergartner or first grader is developing as expected as a reader, writer, and speller? You may want to check these K-1 literacy milestones. Here are a few key facts.

1. Learning to read, write, and spell in English takes time.

English has a more complex alphabetic coding system than languages such as Italian, Finnish, and Spanish. Generally, children can learn to read Italian in about six months. In English, it normally takes two years of explicit systematic instruction in kindergarten and first grade.

Learning to read is a process whereby the child learns to use the alphabetic code to represent or “map to” the words in his or her spoken language. In Kindergarten and first grade the child literally builds new neural networks for words and spellings in the visual processing areas of the brain and automatically connects to already existing systems for spoken English. For each child, new internal neural pathways must be mapped to the sounds of each word being read enabling the brain automatically to connect to that word’s sound and meaning which already exist in the child’s spoken language. Spoken words come first: Reading, a visual process, is dependent on mapping alphabet letters to the sounds and meaning of each word.

2. Your child must look at each word and analyze the letters. No looking at word shapes or guessing from pictures.

Paradoxically, while the reading process is visual, spelling or reading a word starts with the word’s sound. If the child is decoding she must map to the sound by looking at the letters. This is called letter-to-sound mapping (decoding using phonics). If the child is spelling he must think of the word he wants to spell and map it to letters (encoding). This is called sound-to-letter mapping. Decoding and spelling are integrated in the developing brain’s architecture for literacy—they work together.

Spelling and reading always involve matching sound-to-letters or letters-to-sounds. Fluent reading (automaticity) cannot be mastered by memorizing the shape of a word, memorizing the word from picture cards, or looking at picture cues on the page and guessing. The child must see and analyze the letters. In time, the word must be recognized automatically as a single unit. That’s why cognitive science reports that the best predictor of proficient reading is automatic word reading.

Seeing a word and recognizing it automatically makes it a brain word. You are experiencing this process right now as you read the five words cat, yacht, one, for, and four. You may have decoded cat in first grade matching C to the sound /k/, A to the sound /ă/ and T to the sound /t/, but cat and the other words above are now consolidated in your brain’s word form area as a single unit and you recognize each word automatically as a “brain word.” Your brain automatically maps the word you see on the page to an internal neural representation of each word’s spelling without conscious effort.

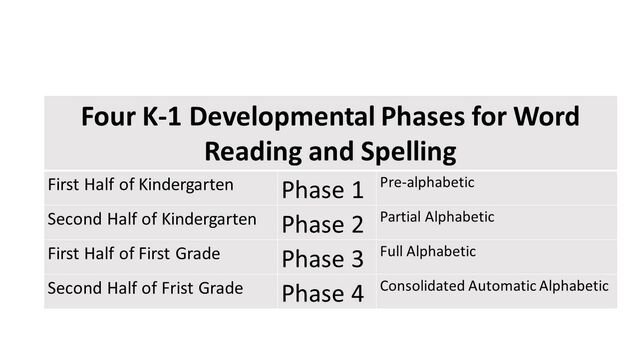

3. Children learn to read and spell English in four overlapping phases.

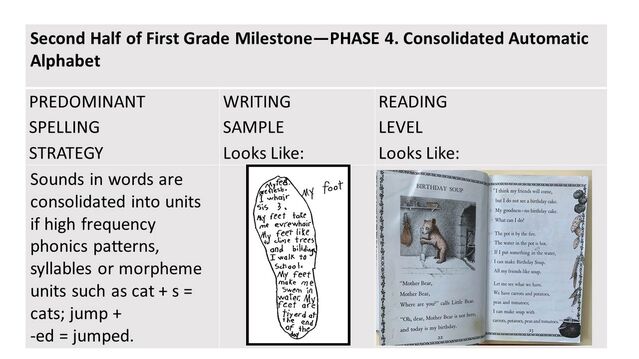

There are two phases expected no later than kindergarten and two phases expected no later than first grade. A child’s move from one phase to the next is gradual and overlapping. The phases are labeled in the chart below to reflect the alphabet knowledge that predominates in each phase.

(Ehri, 2014; Gentry & Ouellette, 2019)

Notice that automatic word reading and spelling are expected at the end of first grade.

4. American students should learn to read, write, and spell by the end of first grade.

This fact supported by science begs the question, “How many brain words or sight words should most kids recognize and spell automatically by the end of first grade?” The answer is around 300 plus. Cognitive science and neuroscience support that with explicit and systematic reading and spelling instruction, 90 to 95% of all children should have 300+ brain words and be reading independently with fluency and comprehension by the end of first grade. This presumes early intervention with kids who are not on track with the phases shown above and includes children who are currently vulnerable for literacy learning who may need early intervention.

5. What are specific developmental grade-by-grade milestones in phase-by-phase development for reading?

In preschool, before most kids are reading and spelling, pencil and paper activity and building their conceptual knowledge and vocabulary by being talked to and read to are important. Joyful engagement with sounds such as alliteration in the beginning sounds of chin, cheek, and cheeseburger, rhyming words as in the Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star song, and teaching a child to write his or her name are all research-based preschool practices. Once a child can write his or her name, he or she is in Phase 1.

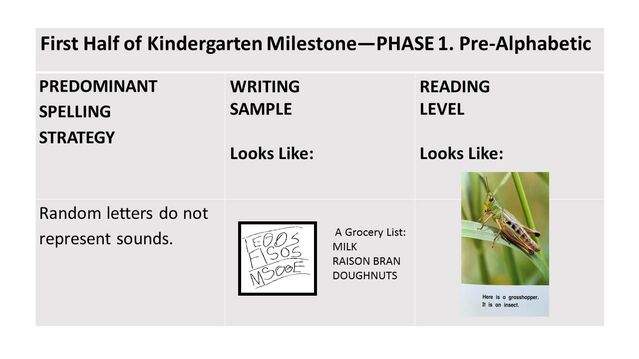

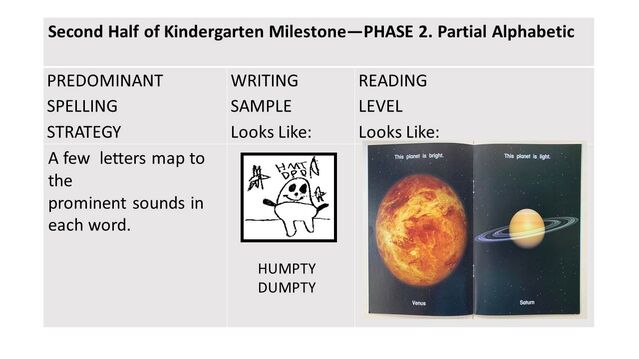

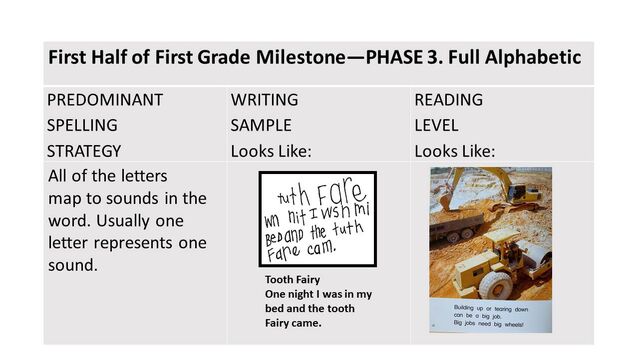

You can see the outcomes of a child’s spelling and reading development by observing developmental changes in a child’s invented spelling from one of the four phases to the next. Grade level and phase level milestones in Table 2 show how invented spelling, writing and text level reading develop hand in hand as children learn to read a mix of decodable and enjoyable texts:

Takeaways: The Truth About Reading

- America has an educational and equity literacy problem. While science says 90% to 95% of all kids should enter Grade 2 reading easy chapter books such as the classic “I Can Read Book,” Little Bear by Else Minarik, only about one-third meet this milestone. Too many American classroom practices and curricula are not based on the latest cognitive science and neuroscience of reading. There must be a call for change.

- Teachers of reading in kindergarten and first grade must be trained in the science of reading and provided with tools such as reading, writing, and spelling curricula based on the science of reading.

Is your child or student meeting these easy to detect milestones? If not, you may have a problem.

References

Ehri, L. C. (2014). “Orthographic mapping in the acquisition of sight word reading, spelling memory, and vocabulary learning.” Scientific Studies of Reading, 18:5–21. DOI: 10.1080/10888438.2013.819356

Feldgus, E., Cardonick, I. and Gentry, R. (2017). Kid writing in the 21st Century. Los Angeles: Hameray Publishing Group.

Gentry, J. R. & Ouellette, G. P. (2019). Brain words: How the science of reading Informs Teaching. Portsmouth, NH: Stenhouse Publishers.

Ouellette, G., & Sénéchal, M. (2017). Invented spelling in kindergarten as a predictor of reading and spelling in Grade 1: A new pathway to literacy, or just the same road, less known? Developmental Psychology, 53(1), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000179

Potter, D. L. (2022). Natural phonics primer: A universal safety net for literacy. Odessa, TX: Independently Published.

Herron, J. & Gillis, M. (2020). Encoding as a route to phone awareness and phonics. Perspectives on Language and Literacy. International Dyslexia Association.