Transgender

Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria

A saga of outrage and science reform.

Posted March 20, 2019 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

This is a story of innovative science, an outrage mob, and how politics and activism insinuate themselves into psychological science; but it is also a story of how one of the innovations of the science reform movement stepped in, albeit a bit awkwardly, to save the day.

Rapid onset gender dysphoria (ROGD) is a new term. Let's unpack it. Gender dysphoria refers to "strong, persistent feelings of identification with another gender and discomfort with one's own assigned gender and sex."

Rapid onset is now easy: It is such feelings and discomfort appearing more or less suddenly and apparently out of the blue.

Is ROGD a real thing? Maybe. Lisa Littman, M.D., and MPA and a researcher at Brown University, conducted a study surveying the experiences of parents involved in one of four online communities for parents of transgender children or "gender skeptical" parents and children. There were 256 completed surveys. Their children were mostly adolescents or young adults.

From the parents' standpoint, about 80 percent of their children announced their transgender identity "out of the blue." The study also presented evidence that the parents reported transgender identity was linked with mental health issues.

The parents reported that those worsened after their child announced the new identity, as did their relationships with the child (keeping in mind that some of the children were adults at the time of the survey).

Other findings also indicated that the parents saw a decline in their children's social adjustment after the announcement (e.g., more isolation, more distrust of non-transgender sources, etc.).

This would probably be of only passing interest to a person with a general interest in psychology but for three things:

- Outrage Mob

- Orwellian "Correction" (a correction-that-did-not-correct-any-errors)

- A Constructive End

Outrage Mob

The publication of the paper was greeted by the outrage of trans activists who denounced the paper and Littman, calling it hate speech and transphobic. Brown initially touted the paper as providing bold new insights into transgender issues, but then removed it from their announcements.

Why such outrage? Trans people have and continue to suffer wicked discrimination and ostracism. Any paper that suggests that trans identities are superficial is likely to be seen as "harming" or "denying" their identities, and the very term "rapid onset" implies that trans identity may not have been indelibly etched in the trans-identifying children of the parents in the study. Throw in links to social isolation and other mental health issues and you have a whole barrage of conclusions that understandably might be viewed as insulting derogations of trans people. And, given the ugly history of marginalization and victimization, a certain sensitivity to threats and derogation among some trans activists is probably understandable.

That, however, is irrelevant to the scientific question of the reality of ROGD. I am not saying "ROGD is real." I am saying that the sensitivity of trans people to bona fide threats to their selves and identities is irrelevant to the scientific question of whether ROGD is real.

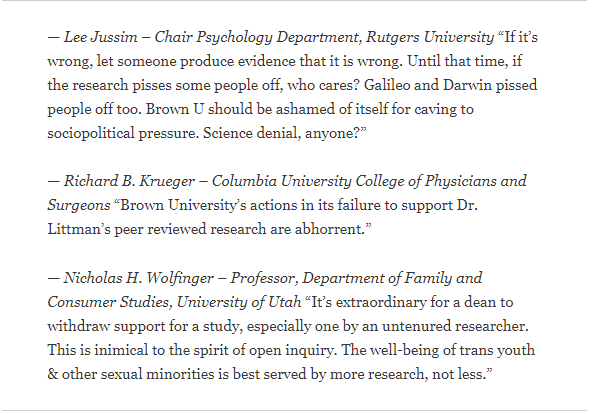

Fortunately, in this case, there was actually a counter-outcry, decrying Brown and the activists for threatening academic freedom. There was even a petition. Which I not only signed, I commented on.

Orwellian Correction

In response to the outcry, PLoS instituted post-publication review of the paper. Post-publication review refers to professional critique and re-evaluation of a paper after it is published. There currently is almost no post-publication peer review in psychology, and I return to this point in the third section.

At the end of that process, PLoS did two things:

- They apologized for their handling of the paper the first time around.

- They persuaded Dr. Littman to revise the paper and post a "Correction."

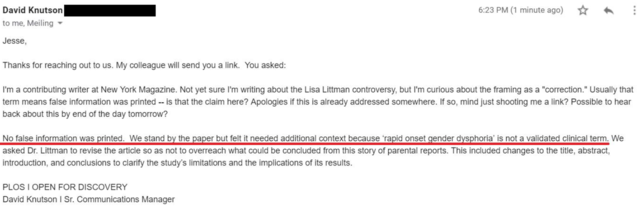

Both the original paper and "correction" are provided in the link above, so anyone can see for themselves that there were, in fact, no corrections. Science journalist Jesse Singal contacted PLoS about this state of affairs, and then posted on Twitter their acknowledgment that there were no errors or falsehoods in Dr. Littman's paper, shown here:

In my experience, a "correction" that is not a correction is unprecedented in psychology and most scientific publishing. Corrections do occur, but primarily for errors — important typos or erroneously computed statistics. In this case, however, the "correction" was nothing more than adding some additional discussion about limitations to the work and some minor reframing to ensure readers understood that the work was preliminary.

What is going on here? It's hard to know for sure, but it fits what psychiatrist Scott Alexander has called "isolated calls for rigor."

He also warns readers to beware of such isolated calls for rigor. Why? He uses a metaphor. Let's say someone argues that there is no such thing as private property. I disagree, but, ok, one could make a serious argument for it. However, if one only argues for this after stealing your cow, but not after you steal their gold, then their argument is not serious because they clearly do not actually believe it. It is just being used to steal your cows.

I sometimes use that phrase, "you are just stealing cows" to call "hypocrisy" in science when people raise plausible-sounding methodological critiques for research that offends them but give a pass to research that uses identical methods but produces conclusions that they like. I have posted several essays on Psychology Today that make just this point, and you can find some of them here, here, and here.

Post-Publication Peer Review Is a Good Thing and It Worked

Science, especially social science, is way, way, way not perfect. Once upon a time, in psychology, scientists acted as if "It is published, therefore it is an established fact." This was dumb. Like really super cosmically dumb, for scientists. Something is not a "fact" just because it was published, especially in psychology, where many classic findings have not been replicated, and, even when they have, their conclusions may not have been justified.

Dr. Littman's revised paper is definitely better than the one first published, not because anything was "corrected" but because bona fide nuances and uncertainties about the paper were better acknowledged.

For example, the research is much more clearly cast as exploratory and preliminary, rather than having "discovered" ROGD. The original did not actually say that, but it was plausibly read as implying that it had. This is GOOD! In fact, Dr. Littman herself, in an interview here, indicated that she felt the revision was actually a constructive improvement over the original.

Upshots?

- Post-publication peer review is a good thing. With the advent of electronic publishing, it is far easier now to make revisions than it was in the olden days when scientific journals were in magazine-like form. There should be more of it.

- However, If post-publication peer review is disproportionately used in response to politically motivated outrage mobs, it will become just another tool for advancing political biases in academic science -- for stealing cows.

I am rooting for #1; I am worried about #2; and, most likely, the real world of scientific publishing will be messy, where both end up occurring to some degree. I am probably as dissatisfied as some of you at not providing a neat, tidy, happy ending.

If you find this essay interesting, follow me on Twitter.