Happiness

How Do You Write a Book?

The twists and turns and squiggles that produced Strength through Peace.

Posted August 25, 2018

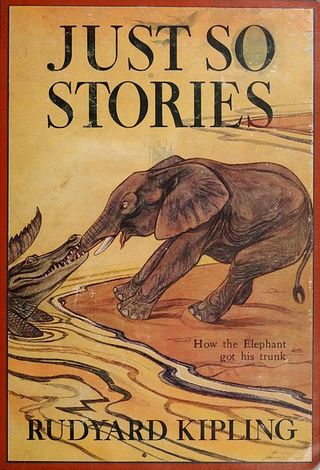

Many people want to write a book, but don’t know how it’s done or where to begin. They worry that you have to have it all planned out or at least outlined or mind mapped before getting going. Hundreds of pages seem like a lot when you start with a blank word doc. Now since at last, por fin, our book about Costa Rica will appear in October, 2018, I think I can illustrate how a book grows and shifts and at times almost writes itself. You don’t need to have written a book to write a book, you just need patience, the ability to take notes and find them again, and 'satiable curiosity, like Kipling’s Elephant’s Child, and that means he asked ever so many questions.

Our book, Strength through Peace, was 10 years in conception and 8 years in the making, containing a false start, a dead end, a pivot and rebirth. Here is why it took so long and how we changed topics and came up with something we think is true and relevant and even funny at times. If you have been following this blog you can see how its focus and tone shifted over the years.

Essentially, our initial idea, that Costa Rica was the happiest country in the world despite its modest size (about the size of West Virginia) and moderate economy (the 50th something in GDP) was wrong. Or at least not robust. To some degree we fell for an advertising scam. We were happy in Costa Rica, so we were ripe for misunderstanding. The data about national happiness per se is a mishmash of weird surveys and expensive data sets. The data we saw in 2011 was based on a single Gallup survey that we could not access without $8k. After downloading and reading several hundred articles about happiness, we came to doubt the entire happiness industry. So, the book floundered, until we realized that there is one fundamental truth about Costa Rica that is terribly important: Costa Rica has had a zero military budget since 1948. It is the largest country in the world with a zero military budget that has been sustained for 70 years. With a sigh of relief, we trashed most of our first efforts about happiness and subjective well-being, and came to grips with analyzing a country without a military. Now we had traction and purpose.

One cannot advertise a book on psychologytoday.com so I will say no more about the book per se. However, I wish to address both the happiness industry and militarism, and its alternative, a non-killing society. This will take 2 postings.

A eally good look at the academic study of happiness can be found here, directed by Ruut Veenhoven in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. You shall see virtually every article about happiness or subjective well-being by nations ever published. Here is a link to Costa Rica's.

The Gallup World Poll of 2009 uses the following question for its survey:

“Here is ladder representing the 'ladder of life'. Let's suppose the top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you; and the bottom, the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder do you feel you personally stand at the present time? 10 best possible life 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 worst possible life.” This question was followed (not preceded) by items on life 5 years ago and 5 years from now.

This is the so called Cantril Ladder, a signature survey item from the happiness movement.

The creepy thing about the survey is the methodology: they ask 1,000 people in each of 155 countries the Cantril Ladder question. The interviews are in person or by phone, but the method is the same: 1,000 people are interviewed in each country, including China, India, Costa Rica, Israel, Finland, or Cambodia. I spoke at some length with the head of Gallup in Costa Rica and he rationalized this by making an analogy: to do a blood count, you only need 1cc or less of blood. A small amount of blood gives consistent results. The problem, however, is obvious: Blood gets mixed as it circulates. Cultures segregate. China has 1.2 billion people, and multiple regional cultures. India has such cultural diversity that it might have close to 1,000 languages and dialects. Even little Costa Rica, with 4.4 million people, shows great diversity. The norms and languages of the Central Valley, where most people live, are different from the East Coast near Limón, where English is common, as is Protestantism and ganja. The West Coast, where we lived, had been settled by cattleman, not the coffee industry, and it has its own norms and dialects, plus a growing beachside and surfing culture. Nonetheless, it seems blindingly obvious that to get reliable data for China requires a larger sample size than to do the same for Costa Rica; otherwise, comparing the two is essentially meaningless.

The last thing you could call me is a statistician, but I was not comfortable with the data. It didn’t make up a book. Furthermore, the government of Costa Rica never measured happiness or subjective well-being because they thought the methodology was inadequate, even though the government publishes a yearly report on the state of the nation, Estado de la Nación. Would that other nations were so meticulous. However, happiness and SWB was never in that survey. Even reports on mental health, including rates of depression, suicide, and other mental illnesses, were handicapped by poor information. Costa Rica has few psychiatrists, most of whom work in hospitals. Furthermore, since suicide is considered a mortal sin by Catholics, the coroner or medical examiner often claims a cause of death to be “natural” even when the dead person is found alone and hanging by the neck. We saw this happen in our little community twice.

We floundered, translated the Estado to compare it to World Health Organization data, or other sources of information. There seemed no way to show that Costa Rica is particularly happy, or even that it has positive mental health. Furthermore, countries like Norway, with very high rates of happiness or life satisfaction, also have high rates of suicide. My eyes got crossed and hair thinned as I pulled it out, metaphorically, trying to unravel this mess.

In 2014, we gave up. We wrote to Oxford that we could not do the book we promised because the data were inadequate, but we had a different idea: we would write a book about a demilitarized, non-killing country, whose economy is not better than middling, but within which the people – by any measure – were happier than one might otherwise expect. Our editor said she had never received such a letter, but she graciously gave us our wish. And that is how Strength Through Peace came to be.