Memory

Why Do People Look Better in Masks?

How amodal completion works in the time of COVID-19.

Posted June 8, 2020 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

We see a lot of people wearing masks these days. Strangers and people we know well. Here is the thing. People tend to look very different. Often much better than without a mask. Why is that?

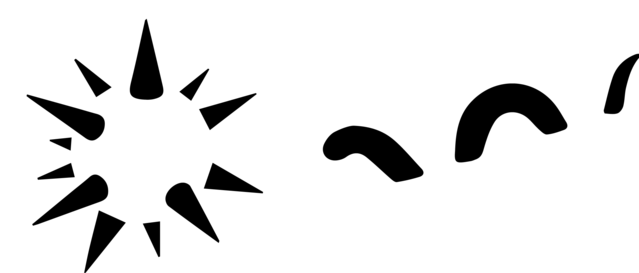

The perception of partly occluded objects is called amodal completion. When we see a cat behind a picket fence, only some parts of the cat are visible, but we are, somehow, aware of the whole cat. Those parts of the cat that are not visible are amodally completed. Here are two famous examples of amodal completion:

The only things that are visible in the image above are really just the black triangles arranged in a certain way. But you see a spiky sphere. The sphere is not visible, strictly speaking, but you can't not see it. On the right-hand side, you see a sea monster, but those parts of the sea monster that are underwater are not visible. Your perceptual system completes these invisible parts.

We now know a lot about the neural mechanisms of amodal completion. It happens very early on in the visual hierarchy, in the primary visual cortex, which is basically the first stop of visual processing after the retina. Some amodal completion relies on top-down information. If you have never seen a sea monster, for example, you would see the figure on the right very differently.

Seeing someone wearing a mask also utilizes amodal completion. The nose and mouth are not visible: There is no part of the retinal image that would correspond to these parts of the face because they are occluded by the mask. But these show up in visual processing already in the primary visual cortex.

Now, if it is someone you know wearing a mask, your perceptual system can rely on memory: You have seen the nose and mouth of this person before, so your episodic memory can supply the information to the visual system that the retina fails to provide. But often, your memory is somewhat vague, especially if it is a person you don't know that well. And when you see strangers, then your memory is of no help.

What information does the visual system use, then, to complete the nose and mouth regions behind the mask in these cases? It can't use (bottom-up) retinal information, because there is no retinal information. And it can't use (top-down) memory, because there is no memory to rely on. It uses generic information about how nose and mouth regions tend to look like.

While you have never seen the nose and mouth of this specific person sitting across from you on the train, you have seen plenty of noses and mouths. Your visual system uses this generalized information to fill in the occluded facial region. It averages faces you have seen and comes up with an image for the occluded region on the basis of this averaged information.

But the averaged face your visual system compiles on the basis of a vast amount of episodic memories of faces tends to give a more aesthetically pleasing image than what is likely to be behind the mask (partly because our memory retains more aesthetically pleasing images better). You are unlikely to amodally complete a large red pimple on the nose behind the mask, but some people do have pimples on their nose. The top-down generic information amodal completion provides is, in some sense, idealized information. And this idealized image which amodal completion provides just looks better than the very-much-non-ideal faces under the masks would.

This is one of the rare and unexpected consequences of the pandemic: The masks force us to have Proustian experiences on an everyday basis. As Marcel Proust says (in Swann's Way, pp. 24-25):

"We pack the physical outline of the person we see with all the ideas we have already formed about him and in the complete picture of him which we compose in our minds those ideas have certainly the principal place. In the end they come to fill out so completely the curve of his cheeks, to follow so exactly the line of his nose, they blend so harmoniously in the sound of his voice that these seem to be no more than a transparent envelope, so that each time we see the face or hear the voice it is our own ideas of him which we recognize and to which we listen."