Health

How Mental Health Links Socioeconomics with Physical Disease

Research on social conditions, mental health, and physical illness.

Posted February 29, 2020 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

This post was written by Grant H. Brenner.

It is no surprise that the "social determinants of illness"—factors related to various forms of deprivation and decreased education related to socioeconomic issues—are associated with poor health outcomes. Adverse childhood experiences alone have been associated with physical and mental illness, causing massive suffering and economic damage. In 2008, The World Health Organization published The Social Determinants of Health, stating:

"Social justice is a matter of life and death. It affects the way people live, their consequent chance of illness, and their risk of premature death. We watch in wonder as life expectancy and good health continue to increase in parts of the world and in alarm as they fail to improve in others."

In 2015, the United Nations challenged us to work toward a better world for all, in "Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development." Numerous studies have established that social factors are correlated with poor health, but large studies have not looked at pathways from social determinants to health outcomes.

Psychiatric illness, in particular, is insufficiently studied both in terms of their direct and indirect impact on well-being. Treating physical health problems, such as cardiac disease, without addressing the underlying contributing factors and causes wastes resources and is ultimately not fully effective, like bailing water out of a leaky boat without fixing the hull.

Over 1,000,000 Person-Hours of Data

A recently published study in The Lancet Public Health, "Association between socioeconomic status and the development of mental and physical health conditions in adulthood: A multi-cohort study" by Kivimäki and colleagues (2020), analyzed databases from Finnish and UK health cohorts, covering 1,110,831 person-years to see how socioeconomic risk factors lead to mental health-related issues, and in turn, how these issues interact with and increase the risk of later-life physical health problems.

The researchers included data from two Finnish studies, the Health and Social Support study and the Finish Public Sector study, including 109,246 adults age 17-77 over 18 years, and confirmed their findings using a large UK cohort from the Whitehall II study, including nearly 10,000 people studied over a 20-year span. They derived measures of "area deprivation," a combination of educational achievement, employment status, and housing information for specific geographic areas covering 250 by 250 square meter pixels, as well as additional independent measures of education, and in the UK replication study, a measure called "the British civil service occupation grade," a composite of key socioeconomic factors.

The researchers analyzed area deprivation and educational status along with medical records registries covering over 300,000 hospitalizations across the three groups. They controlled statistically for a variety of potential confounding factors to ensure that the relationships they determined were not due to hidden factors.

For example, if depression increases cardiac disease, the analysis would factor out the role of cigarette use to see if the relationship was truly from depression, rather than as a result of increased smoking from depression.

How Do Social Determinants Impact Mental Illness and Later Physical Health?

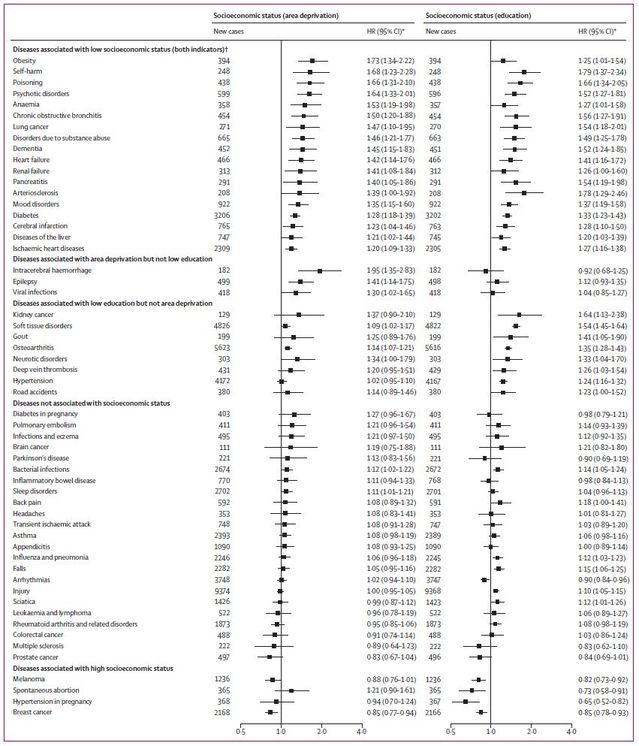

Fifty-six1 different medical and psychiatric conditions were identified from the overall hospital records. Of these 56 conditions, low socioeconomic status was associated with an increased risk for 18 of them (32.1 percent):

- Self-harm

- Poisoning

- Psychotic disorders

- Arteriosclerosis

- Chronic obstructive bronchitis (COPD)

- Lung cancer

- Dementia

- Obesity

- Substance Use Disorders (SUDS)

- Pancreatitis

- Heart failure

- Anemia

- Mood disorders

- Renal failure

- Diabetes

- Cerebral infarction (stroke)

- Heart disease

- Liver disease

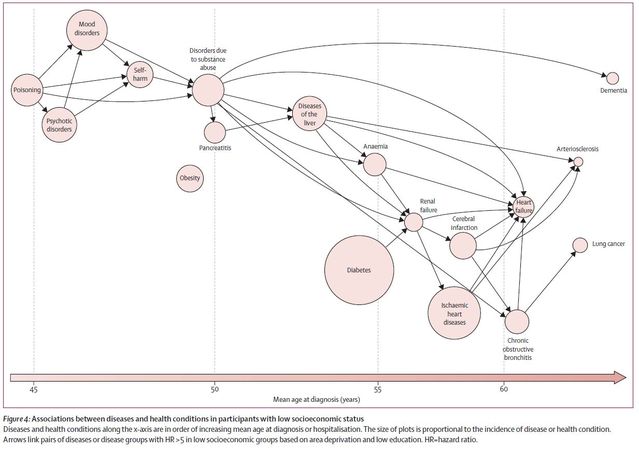

Of these, 16 were associated with at least a five-fold increased risk ("hazard ratio," or HR), forming a "cascade of inter-related health conditions." Researchers were able to calculate how psychiatric conditions earlier in life increased the chances of various negative health-related behaviors and subsequently serious medical conditions. For example, mood disorders diminish self-care, leading to self-harm and subsequent substance-related problems. Those, in turn, correlate with liver problems and future issues related to kidney, cardiovascular, brain, and other diseases, as illustrated here:

This work significantly extends current research by mapping out probable causal relationships over time, showing a clear sequence of interconnection between socioeconomic risk factors, early-life mental illness, and self-destructive behaviors, including substance use disorders, and downstream medical illness affecting all major organ systems.

Notably, not all of the 56 illnesses identified from hospital records were impacted by social determinants. Four conditions were associated with high socioeconomic status: spontaneous abortion, melanoma, hypertension in pregnancy ("eclampsia"), and breast cancer.

Many of the relationships among social determinants, mental health, and physical health were stronger earlier on, highlighting the role of shorter-term effects. For example, financial strain can increase depressive symptoms, causing feelings of helplessness and low self-esteem, increasing feelings of powerlessness, decreasing resilience, and leading to the use of harmful coping strategies, including alcohol use.

Alcohol use, in turn, worsens depression and further impairs functioning, preventing adaptive responses to circumstances. Interactions are important in the longer term as well, and it takes time for serious medical problems to develop years after self-harm and self-neglect. Furthermore, later-life conditions, such as cardiovascular and brain disease, increase the risk of depression, worsening the vicious circle.

Even when people have recovered from early-life emotional and psychological problems, the damage to the body may already have been done—sometimes with tragic results when those who may not have cared whether they lived or died when younger have come to thrive later in life.

The Good News

Thankfully, improving self-care and lifestyle later in life has a major positive impact on health. Quitting smoking is a great example of this, and exercise and quality sleep are beneficial regardless of other factors.

Positive psychiatry makes a strong point about how important it is to seek "wellness in illness," improving modifiable resilience and health factors, and striving to flourish regardless of circumstances. Targeting mental illness, improving self-care, and reducing self-harming behaviors will interrupt the sequence that the Lancet authors have identified, but public health efforts do not yet take this into full consideration, as the study authors conclude:

"Our findings have important implications for research and public health policy. The pattern of mental health problems and substance abuse preceding socioeconomically patterned physical diseases is not reflected in global strategies to prevent diseases. The WHO Sustainable Development Goals and the Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases, for example, have their main focus on physical health; the 2013-2020 WHO Global Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases and the Global Burden of Disease Collaboration do not include socioeconomic disadvantage as a modifiable risk factor. Moreover, treatment of psychiatric disorders, physical disease, and substance abuse is often split between health-care and social services. This approach is unlikely to be optimal for tackling problems with shared health determinants, including socioeconomic inequalities in morbidity. The 2019 Lancet Commission drew attention to the need to improve the protection of physical health in people with psychiatric disorders; our findings suggest this is particularly important for people living in socioeconomic disadvantage."

List of Illness and Correlations With Area Deprivation

References

A Psychiatry for the People post ("Our Blog Post") is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. We will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by your reliance on information obtained through Our Blog Post. Please seek the advice of professionals, as appropriate, regarding the evaluation of any specific information, opinion, advice, or other content. We are not responsible and will not be held liable for third party comments on Our Blog Post. Any user comment on Our Blog Post that in our sole discretion restricts or inhibits any other user from using or enjoying Our Blog Post is prohibited and may be reported to Sussex Publishers/Psychology Today. Neighborhood Psychiatry. All rights reserved.