ADHD

Global Use of ADHD Medication Is Rising

New research from Lancet Psychiatry refreshes the picture.

Posted October 2, 2018

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD, often still referred to by an older acronym “ADD”) is a psychiatric condition characterized by difficulties with focus, impulsivity, and over-activity. According to CDC findings, ADHD is on the rise. As of November 2013, it is estimated that 11 percent of children from ages 4 to 17 have been told they have ADHD at some point. This is up from an estimated 7.8 percent in 2003. Boys are diagnosed with ADHD almost three times as often as girls, and this may be because clinicians are less prone to interpret symptoms in girls as ADHD and miss the proper diagnosis, though this trend is changing. And it isn’t only kids where ADHD is being diagnosed more often; parents themselves are being diagnosed with ADHD much more frequently than they used to, up over 40 percent as of 2011.

ADHD, surrounded by controversy

It is a controversial diagnosis, and there are camps that believe ADHD is much more common than recognized, and therefore under-diagnosed and under-treated, and there are those who assert that ADHD is rampantly over-diagnosed, and not a legitimate psychiatric diagnosis, often associated with concern that children are being medicated unnecessarily, for “just being children”. There are concerns that rising ADHD rates are the result of environmental changes, with hand-held devices and fast-paced information flow and relatedness demanding that the brain adapt to an ADHD-world. There are concerns that medication use is driven by commercial interest. People have very strong feelings about this, and it is polarizing. As there are biological differences associated with ADHD, including genetic factors such as how fast neurotransmitters are broken down in the brain, and different levels of activity in executive areas of the brain, the interaction between nurture and nature deserves attention.

Parents and clinicians alike understand that apprehension comes with giving children medication, and how receiving a diagnosis and treatment may lead to stigma and feeling pathologized, which in turn my reduce self-esteem. On the flip side is the high pressure to perform, which is epidemic in our society. Whether you are getting a proper diagnosis and treatment or taking medication to keep up with everyone else because you have to get straight As, do extracurriculars, stay up late and not sleeping enough (also interferes with cognition), and still try to have normal social and emotional development. It is, sadly, a serious problem how our children are being raised, and we don't know the full scope of what it portends for the future, but rates of anxiety are also through the roof, and social and emotional development takes a backseat, with dire results.

Beyond being a psychiatric diagnosis, to add further complexity ADHD is considered by many to be a way of being in the world, not quite personality, but a creative and kinetic style of thinking, feeling and living which could be considered a normal variation. This is important to many, as it de-pathologizes the condition, but also runs a risk of delaying effective treatment. And of course, ADD is used casually, as in, “I’m totally ADD--just keep emailing me until I respond”.

Diagnosis is meant to guide proper treatment

This brings up the important point about diagnostic accuracy. A condition can be over-diagnosed, and it can be under-diagnosed, but in a more subtle sense (we are talking about the sensitivity and specificity in statistical terms), it is more about how the diagnosis is tuned, so to speak. A particular clinician diagnosing ADHD on an exam and by history or a test designed to look at neurocognitive markers of ADHD isn’t going to be perfect. There will be false positives, in which someone without ADHD is diagnosed with, and false negatives, in which a true diagnosis of ADHD is missed. In the recent past, user-friendly ADHD tests have hit the market, which report better accuracy than clinician diagnosis, and are easily done in the office on a tablet or laptop, rather than requiring days of intensive testing. ADHD is big business, for sure.

So, depending on how many false positives and negatives there are, versus true positives and true negatives, the patient may receive treatment which is not necessary. In the other case, the patient may not receive treatment which can be very helpful. Muddying the waters even further is that, as with the general public, there are clinicians who do not “believe” in ADHD, and may discourage patients from getting evaluation and treatment. Or, doctors who see ADHD everywhere, and go along with families where the kids may have difficulty in school from a learning disability, or depression and anxiety, or problems in the family, and get a fast diagnosis of ADHD. It is worth noting that quick diagnostic screens often used in office and online themselves are not great indicators of a real ADHD diagnosis if they are not part of a comprehensive evaluation. However, many folks I see have used such self-report scales, or come in with a sheet from another clinician, with a seemingly firm diagnosis of ADHD and a long history of taking medication.

Regarding treatment, aside from medications, treatments for ADHD include neurofeedback and therapy, organizational and time-management coaching, classroom and environment modification, as well as complementary and alternative approaches among others. The most commonly prescribed medications for ADHD are stimulants, which have significant risks for adverse events, including appetite suppression potential growth interference, cardiovascular risks, and risks of addiction, and should not be prescribed lightly.

These risks, for example the risk of addiction, are considered to be low when stimulants are used appropriately for ADHD. But medication may be obtained inappropriately and misused, sometimes by design which makes providers wary, but often by quick inaccurate diagnosis, and medication may be passed on to others (who may have adverse reactions), and used recreationally or for performance enhancement. This, by the way, is why psychiatrists are often thoughtful in prescribing stimulants, requiring regular visits and more thorough evaluation. This class of medications have been prescribed and abused as “diet pills”, and are also sometimes used off-label for addressing symptoms of low energy and concentration, as with major depressive disorder, as well.

Medicating the world

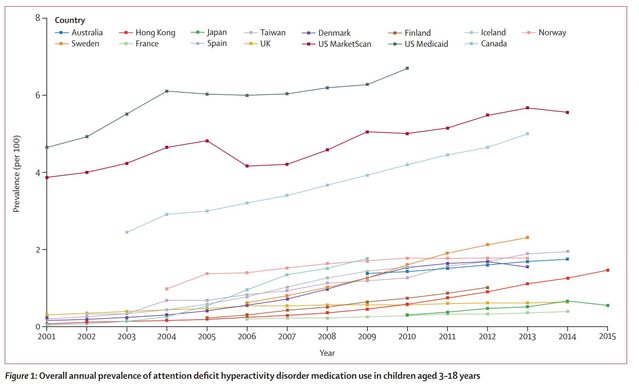

With these considerations in mind, a multi-national group of researchers (Raman et al., 2018) conducted a meta-analysis of stimulant use across the globe. The looked at population-based data bases in four Asian and Australian areas, two North American regions, three in western Europe, and five areas in northern Europe, totaling 13 countries and one Special Administrative Region. They looked at data for people 3 years and up from January 2001 until December 2015, and estimated the percentage of the population yearly who were taking ADHD medication. They looked at data from 154.5 million people, and found a range of prevalence in medication prescription in children 3 to 18 years old ranging from 0.27 percent to 6.69 percent (in the US). ADHD medication use went up over time in all countries studied, and was highest in North America.

For adults over 19 years old, ADHD medication prevalence was much lower, not going above a little bit shy of 1.5 percent at its highest, also in North America. Methylphenidate, commonly called Ritalin, was the most commonly prescribed medication—except in the US, where amphetamine was most common. As with prior data, males were prescribed ADHD medications more often than females, ranging from over a 6-fold increase, to more even proportions. Interestingly, the highest ratio of boys to girls were in Finland (over 6:1), Hong Kong (nearly 6:1), and the UK (almost 5.5:1). In the US, boys received ADHD medications at 2.2:1, down from the CDC estimates cited. This change may be a result of an effort to look more carefully for ADHD in girls, and is a positive change if you think ADHD is being better diagnosed and treated.

Overall, there were many differences among countries in ADHD medications. These differences, too numerous to spell out here, relate to prescribing practices in different regions, whether medications are prescribed before non-pharmacological approaches, and differences in data collection methodology, among other factors.

The big picture

The take-home message is that the world's population is increasingly being prescribed stimulant medications, primarily for ADHD. Does this reflect that we are more accurately diagnosing a serious condition, reducing suffering, and increasing quality of life and function, over-medicating children and adults for commercial reasons and to compensate for an environment to which we are not well-suited, a normal variation to be embraced and worked with, rather than around, or something else? On a whimsical note, does it mean our society is becoming so "ADD" that the whole planet needs drugs to focus?

There is no question that many people diagnosed with ADHD benefit greatly from treatment, often a combination of medication and other approaches. When medications work, they are often dramatically effective, offering relief to people who have been struggling for years not only with difficulty functioning, but also the emotional fallout from the disparity between often being very bright and capable while performing at a reduced level. This can be a major problem across the age span, and in children affects adult identity and career, as the negative effect on self-esteem, along with anxiety, depression and substance use, take their toll. This highlights the importance of overall diagnostic accuracy to pick up ADHD when it is present, and exclude the diagnosis when it is not so that any treatments offered are more likely worth the risk.

References

Trends in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder medication use: a retrospective observational study using population-based databases Sudha R Raman*, Kenneth K C Man*, Shahram Bahmanyar, Anick Berard, Scott Bilder, Takoua Boukhris, Greta Bushnell, Stephen Crystal, Kari Furu, Yea-Huei KaoYang, Øystein Karlstad, Helle Kieler, Kiyoshi Kubota, Edward Chia-Cheng Lai, Jaana E Martikainen, Géric Maura, Nicholas Moore, Dolores Montero, Hidefumi Nakamura, Anke Neumann, Virginia Pate, Anton Pottegård, Nicole L Pratt, Elizabeth E Roughead, Diego Macias Saint-Gerons, Til Stürmer, Chien-Chou Su, Helga Zoega, Miriam C J M Sturkenbroom, Esther W Chan, David Coghill, Patrick Ip, Ian C K Wong. Lancet Psychiatry 2018; 5: 824–35