Bipolar Disorder

How Do Couples Best Cope with Bipolar Disorder?

New research on real-world approaches to staying positive and healthy.

Posted July 4, 2018 Reviewed by Davia Sills

By Grant H. Brenner, M.D., FAPA

"I'm not the kind of person who likes to shout out my personal issues from the rooftops, but with my bipolar becoming public, I hope fellow sufferers will know it's completely controllable. I hope I can help remove any stigma attached to it, and that those who don't have it under control will seek help with all that is available to treat it." —Catherine Zeta-Jones

According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), bipolar disorder is a psychiatric condition which affects 2.8 percent of the U.S. population in any given year, and over the course of a lifetime affects 4.4 percent of people. Approximately 83 percent of people will have very severe symptoms, and an addition 17 percent will have moderately severe symptoms. Rates of bipolar disorder are similar for men and women, and bipolar disorder is most commonly diagnosed in the mid-20s, within a broad range of age of onset.

Bipolar disorder is a complex illness, with seemingly contradictory symptoms from severe depression to extreme euphoria and agitation (“mania”), and everything in between, including low-grade manic episodes, called "hypomanic" episodes, and combined depression and mania, called "mixed" episodes. There are several sub-types of bipolar disorder, and it is considered to be a condition requiring long-term management. Many with bipolar disorder have difficulty accessing effective diagnosis and treatment, leading to further suffering for themselves and those close to them. Bipolar disorder is often complicated by the presence of other psychiatric conditions, including anxiety disorders, ADHD, and substance use disorders, exacerbating the situation.

While excitement, energy, and measured euphoria can be pleasant for patients and people close to them, depression is often chronic and difficult to treat, and manic phases may include, in addition to euphoria and periods of heightened productivity, reckless behavior, agitation, sleeplessness, impaired judgment and decision-making, and more severe symptoms, leading to long-term negative repercussions from excessive spending, sexual, and other highly problematic, sometimes frankly dangerous, behaviors.

Unfortunately, as a result, emotions in bipolar disorder often become suspect, as people may question whether feelings are “real” or due to the illness. Suicide rates in bipolar disorder are double those in major depressive disorder, also called “unipolar depression” (Chen & Dilsaver, 1996), with suicide attempts in up to 50 percent of bipolar patients (Jamison, 2000), and death from suicide reportedly as high as 20 percent (Tondo, Isacsson & Baldessarini, 2003).

The diagnosis of bipolar disorder can be difficult, as treatment is sought for depression rather than hypomania, and so appropriate treatment is often delayed. Even when a proper diagnosis has been made, it can be challenging to find medications and other treatments which are both effective and acceptable. Those with bipolar disorder may find remaining in treatment a challenge, especially when it comes to taking medications which may blunt the appealing aspects of the illness, while possibly causing significant negative side-effects and medical complications.

Couples with bipolar disorder

Understandably, bipolar disorder presents challenges for couples because of the range of symptoms, lack of stability over time, consequences of behaviors and impairment from mania and depression, and difficulty finding and maintaining effective treatment. Divorce and separation are two to three times more common among couples with a bipolar partner (Kogan et al., 2004), bringing home the damage the condition can cause to relationships. Couples deal with recurring episodes of depression, mania, and other symptoms, feelings of helplessness, difficulty with closeness due to the need to manage emotions carefully, and a tendency to use denial to manage the impact of the illness on the relationship and their lives (Ablon et al., 1975), though denial may be less prominent (and necessary) as more effective treatment has become available.

New research on how couples cope with bipolar disorder

In the current study from the journal Family Relations, Granek and colleagues (2018) use qualitative research measures to discern the main strategies actual couples use in coping with bipolar disorder. While prior research has explored coping in bipolar and related psychiatric conditions, this is the first research to survey patients and partners in a clinical setting and analyze their narratives to distill out major recurring themes.

Working with couples in an outpatient bipolar clinic in Israel, researchers conducted detailed interviews with a total of 21 participants, including nine married couples and three partners whose spouses chose not to participate. Eleven participants were diagnosed with Bipolar I disorder, seven women and four men, and all study participants in treatment were required to have been stable for at least one month prior to the interview. Patients were between 30 and 68 years old, with an average of 50 years of age, and partners were from 39 to 70 years old, averaging 52 years old. Marital length ranged from 4 to 45 years, on average 22 years, and many couples had children.

Interviews were guided and open-ended, conducted privately and individually, to allow participants to speak freely about their experiences. The narratives were analyzed using the grounded theory method, with researchers independently combing the transcripts for common themes, coding and analyzing for those themes, and continuing until no new information could be gleaned by further analysis. The resulting coping strategies were identified for PWBD (persons with bipolar disorder) and partners.

Study findings

Overall, shared coping strategies included seeking professional help, seeking social support, emotional, instrumental (practical), and religious coping approaches. Some coping strategies were used by both partners and PWBD, and others were different between groups.

1. Professional support: Both PWBD and their partners reported seeking support from professionals, including therapists, nurses, and physicians, to be essential for effectively coping with bipolar disorder, especially during difficult times. In addition to providing appropriate care in general, and responding with clinical interventions during more symptomatic periods, participants reported that professionals provided safe and confidential emotional support, particularly when others, notably their spouses in the case of partners of PWBD, were unavailable. For PWBD, when they were uncertain about whether they were doing well, professionals were able to respond appropriately, offering both medical care as well as reassurance if there were no concerns.

2. Social support: Both partners and PWBD described providing support for one another to the extent possible. In addition to providing pragmatic help (e.g., keeping track of medications, helping get to appointments, stepping in to take care of home and children during hospitalizations, etc.), participants consistently reported that open communication, free from secrets, and a decent sexual relationship were important to long-term coping and relationship stability.

Participants noted that support from parents was very important for effective coping, including support from their own parents as well as in-laws. Again, support was both emotional and practical. Parents encouraged optimism and determination during difficult times, including giving breaks by taking over caregiving and other responsibilities when necessary. PWBDs specifically noted the importance of friendships for coping. Friends helped out with important basic issues, such as getting meals, in addition to providing in-person, one-on-one support. Partners also reported getting support from friends to a lesser extent, typically in times of heightened stress.

Children were reported by both PWBD and partners as significant sources of support, both practical and emotional, as well as being sources of strength and motivation. PWBDs only noted that support and understanding from employers, especially trusted managers with whom they could safely confide, was important when being understanding and flexible with missed work due to illness. Likewise, clergy were important sources of support and direction for PWBD, but not their partners, and at times were critical in urging them to accept necessary treatment during times of uncertainty.

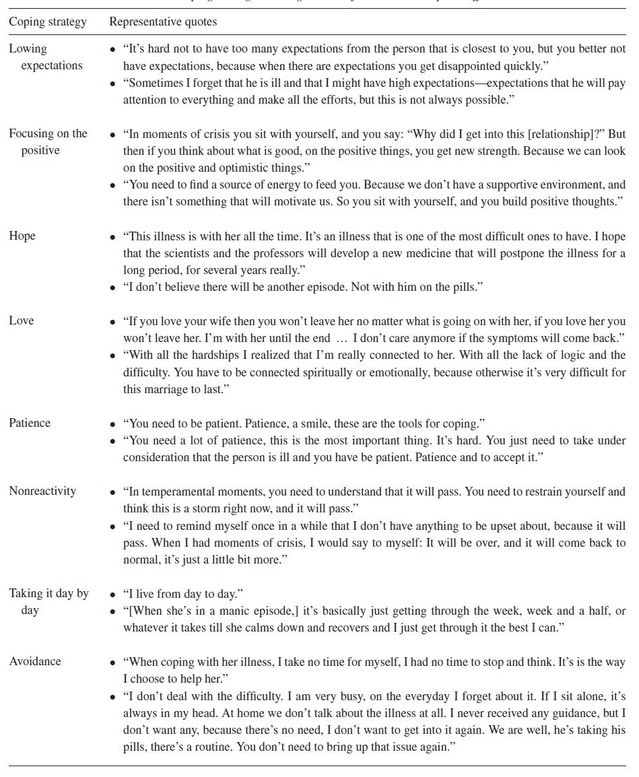

3. Emotional coping strategies: In general, partners were more likely to use emotional coping strategies compared with PWBD. Partners managed expectations to avoid disappointment, focusing on positives over negatives in remaining resilient. Partners noted coping by maintaining hope that future treatments could be more effective, both emerging treatments as well as the current plan, and discussed the importance of love and patience. Partners specifically reported that it was helpful to avoid strong emotional reactions, using acceptance and taking it day-by-day during more difficult periods. Some participants noted that it was helpful, at times, not to think about problems related to bipolar disorder.

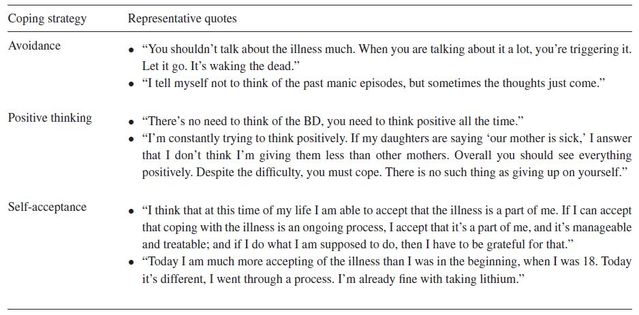

PWBDs also reported not thinking about the impact of bipolar disorder excessively, instead focusing on positives to cope. For PWBDs, acceptance of having bipolar disorder, and self-acceptance in general, helped them get through difficult times and maintain care during more stable periods when they might otherwise be tempted to drop routines, engage in triggering activities, and discontinue treatment, both medication and therapy.

4. Instrumental coping strategies: PWBDs reported heavier weighting for practical approaches to coping: for example, taking medications as prescribed, getting labs checked when required, attending appointments as scheduled, and avoiding those things which might trigger relapses, such as alcohol and drugs. Accepting that they had bipolar disorder, and seeing that taking medication consistently helped prevent mania and depression, and maintaining normal routines, was important for coping. PWBDs noted that being involved in day-to-day activities, such as being busy with work and family, kept them occupied and distracted from negative thinking. Partners, by contrast, primarily discussed the importance of taking breaks from caregiving, especially during hard times.

5. Religious and spiritual coping strategies: Both partners and PWBDs described religion, spirituality, and faith as being important to coping. For partners, religion provided a framework for accepting adversity, and faith in God for protection and healing. PWBDs also noted the importance of faith and highlighted that regular rituals bolstered resilience and that religious teachings supported acceptance of suffering and seeking happiness in life.

Further considerations

Bipolar disorder can be challenging to live with for individual and couples. Having a detailed understanding of what coping strategies are useful for maintaining stability in long-term relationships from experienced couples identifies tools which may be helpful for couples. Because of high rates of separation and divorce among couples coping with bipolar disorder, and heightened risk due to the illness itself, it is important for couples to do everything reasonable to build resilience in order to enjoy the greatest individual and shared quality of life they can, focusing on positive and constructive efforts, rather than getting caught up in negative, destructive cycles.

Resilience in general is bolstered by active coping, identifying and preventing problems before they happen, cultivating a strong sense of agency and a healthy sense of control in dealing with adversity, fostering flexible thinking, challenging oneself in healthy ways to grow stronger, maintaining good self-care and healthy routines, using social support, and practicing religion and spirituality effectively as applicable. Based on this research, couples with bipolar disorder describe coping strategies consistent with good practice, rather than relying on more brittle coping, such as denial, though distraction can be a healthy and necessary coping tool at times if it does not lead to long-term avoidant coping, which allows problems to grow unchecked.

Future research will be important to sort out which coping strategies are most effective, and how to integrate them into treatment, including therapeutic interventions for couples. Additional factors, including personal, religious, and cultural differences, play a significant role in determining what coping strategies are most useful and may fruitfully be explored further. Based on the current research, couples report do best when they are open and communicative, supporting one another pragmatically and emotionally, setting aside time for self-care and personal time, and using external supports and clinical care appropriately. By collaborating to manage bipolar illness, couples can better maintain longer periods of well-being and achieve a greater sense of efficacy in dealing with a serious challenge together.

For additional reference:

Partner Coping Strategies

PWBD Coping Strategies

References

Tondo, L., Isacsson, G., & Baldessarini, R. J. (2003). Suicidal behaviour in bipolar disorder. CNS Drugs, 17, 491–511. https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200317070-00003

Kogan, J. N., Otto, M. W., Bauer, M. S., Dennehy, E. B., Miklowitz, D. J., Zhang, H. W. . . . Thase, M. E. (2004). Demographic and diagnostic characteristics of the first 1000 patients enrolled in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Bipolar Disorders, 6, 460–469.

Chen YW, Dilsaver SC. Lifetime rates of suicide attempts among subjects with bipolar and unipolar disorders relative to subjects with other Axis I disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:896-899.

Jamison KR. Suicide and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:47-51.

Ablon, S. L., Davenport, Y. B., Gershon, E. S., & Adland, M. L. (1975). The married manic. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 45,

854–866.

Granek L, Danan D, Bersudsky Y & Osher Y. (2018). Hold on Tight: Coping Strategies of Persons With Bipolar Disorder and Their Partners.Family Relations (2018), 27 June.