Personality

7 Core Pathological Personality Traits

New research examines emerging trait-based approaches to personality disorder.

Posted November 1, 2020 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

by Grant H. Brenner

There is no unified consensus on how to evaluate and define personality, though there are many approaches. Models include the Five-Factor Model (FFM or Big Five) consisting of openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (OCEAN). The HEXACO model has six factors, overlapping with the FFM: honesty-humility, emotionality, extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness.

Some traits and clusters of traits are more problematic leading to difficulty with self-regulation, relationship issues, substance use disorders, and mental illness. Others are associated with greater personal and professional success. Many are fine in moderation and only become problematic in extremis.

Conscientiousness, agreeableness, and lower neuroticism are associated with better average function (though there are downsides as well, for example being too agreeable may mean being insufficiently assertive). Openness and extroversion are more characteristic of orientation to life experiences and relationships.

Another familiar model is the Jungian-based Myers-Briggs, identifying 16 types based on four dimensions: introversion-extroversion, sensing-intuition, thinking-feeling, and judging-perceiving. There are many others, often colorful or imaginative, used to try to predict and enhance performance, evaluate hires and promotions, and help build effective teams.

Popular models tend to focus on strengths, and frame problematic traits in a positive way—or sidestep them altogether.

From Adaptive to Maladaptive

Personality is not the same as a personality disorder, which is associated with profound, lifelong impairment in multiple domains (e.g. personal, professional, relationship), untold suffering, and increased mortality and morbidity, affecting 6 to 10 percent of the population. A personality disorder diagnosis is not made lightly, but rather demands thoughtful and thorough evaluation.

Notably, a recently published landmark study (Tiosano, et al., 2020) followed over 2 million adolescents from 1967 until 2011, finding a nearly 1.5-fold increase in mortality among men with personality disorders, and an over 2-fold increase for women.

Psychiatry takes psychological models into consideration in revising diagnostic criteria and approaches to diagnosis. The DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual), introduced in 2013 after 10 years of development, moved toward controversial diagnostic changes in many areas, including personality.

The prior DSM-IV used a three-cluster model of personality disorders with Cluster A referring to paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personalities, Cluster B to borderline, narcissistic, antisocial, and histrionic personalities, and Cluster C avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive personalities. Despite being organized into clusters, many traits are shared across personalities.

The DSM-5 retained the traditional classification while formally recognizing the need for future consideration of updating to a trait-based system: the Personality Inventory for DSM-5 (PID-5, measured with a 220-item instrument). This investigative model is based on the alternative model of personality disorder (AMPD) with 25 traits thought to be organized around five underlying factors: negative affect, asociality, disinhibition, antagonism, and psychoticism.

A proposed hybrid model was ultimately not adopted, but would have defined fewer personality disorders, namely borderline, obsessive-compulsive personality (not the same as obsessive-compulsive disorder), avoidant, schizotypal, antisocial, and narcissistic personality disorders.

Additional research is being conducted in light of the recommendation to explore alternative constructs. One study, for example, found the AMPD approach to be no better (and no worse) than the traditional three-cluster model on an important measure of validity (McCabe et al., 2020). Quilty and colleagues (2020) found the DSM-5 approach to be valid and well-correlated with clinician ratings. It is a work in progress.

Getting to the Bottom of Pathological Personality

Gutiérrez and colleagues (2020) took a different tack, comparing the PID-5 and the Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology-Basic Questionnaire (DAPP-BQ), a well-validated 290-item instrument covering 18 sub-factors comprising four overarching factors: emotional dysregulation, inhibition, dissocial behavior, and compulsiveness.

The research team recruited 414 outpatients from a personality disorder treatment unit for the study, the majority (65.2 percent) of whom met the criteria for psychiatric illness (e.g. mood or anxiety disorders, trauma and stress-related conditions, eating, substance use, and other disorders, in addition to personality disorders. The data from the PID-5 and DAPP-BQ were analyzed using hierarchical factor modeling to look at big-picture and granular aspects of personality pathology.

Findings

They found substantial overlap between the PID-5 and DAPP-BQ, with a couple of notable differences. Compulsiveness was explicit in DAPP-BQ, for example, whereas psychoticism was emphasized more by PID-5.

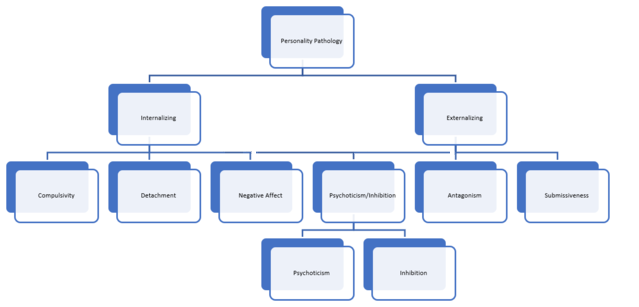

On a general level, there were two main types of personality pathology: Internalizing (in relation to oneself e.g. depression, bottling up feelings, withdrawal, etc.) and externalizing (in relation to others and the world, e.g. lashing out at others, behaving impulsively, acting out, etc.).

The hierarchical analysis went as follows (Figure 1): Internalizing further differentiated into compulsivity, detachment, and negative affect. Externalizing broke down into antagonism and submissiveness. Psychoticism and disinhibition overlapped, belonging both to internalizing and externalizing, resolving into distinct factors.

All told, the bulk of personality pathology reflected in these measures was accounted for by 7 basic elements:

- Compulsivity

- Detachment

- Negative affect

- Psychoticism

- Disinhibition

- Antagonism

- Submissiveness

These factors, in various combinations, make up the different personality disorders. Again, while there is overlap, they come together to determine distinctively different diagnostic categories.

Implications

While trait-based (dimensional) approaches to personality pathology may be statistically equivalent to the traditional ones, being able to discern underlying building blocks adds value. Understanding personality helps us to make sense of others' behavior, as well as our own.

It’s useful individually for building candid self-awareness. Conceptually, while many people find a traditional diagnosis useful for accepting the need for and finding appropriate treatment, others find the possible stigma and labeling associated with a personality disorder diagnosis to be a significant barrier to care. Precise descriptives make it easier for many to get at thornier issues.

For clinical care, the ability to measure and track changes in core personality drivers identifies potentially high-yield targets above and beyond categorical models.

Current approaches to treating personality disorders (e.g. dialectical behavioral therapy DBT for borderline personality) are often effective, but treatment for personality pathology, in general, is challenging. DBT focuses on concrete tools including mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotional regulation, and interpersonal skills training, for example. These can be understood as focusing on underlying areas like negative affect, disinhibition, and antagonism, as well as on the macro level.

Clinicians offer more personalization and compassion to therapeutic efforts by engaging patients collaboratively and meeting people where they are. This includes identifying underlying traits and using self-reflective awareness to build motivation, resilience, and agency, in working toward an integrated approach to personality change.

Trauma and neglect are often contributors to personality disorders, increasing the likelihood of physical and mental illness, underlining the importance of person-centered, humanistic care. Research is ongoing to understand whether dimensional approaches to personality, and other novel approaches,1 will become standard.

Facebook/LinkedIn image: Roman Samborskyi/Shutterstock

References

1. E.g. “transdiagnostic approaches,” which look at underlying features of conditions like depression and anxiety to derive a more accurate, and useful, picture, or "biotypes," which look for underlying varieties of mental illness based on computational models rather than clinical experience.

Note: A Psychiatry for the People post ("Our Blog Post") is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. We will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by your reliance on information obtained through Our Blog Post. Please seek the advice of professionals, as appropriate, regarding the evaluation of any specific information, opinion, advice, or other content. We are not responsible and will not be held liable for third party comments on Our Blog Post. Any user comment on Our Blog Post that in our sole discretion restricts or inhibits any other user from using or enjoying Our Blog Post is prohibited and may be reported to Sussex Publishers/Psychology Today. Neighborhood Psychiatry. All rights reserved.