Coronavirus Disease 2019

Why Aren't Some People Taking COVID-19 More Seriously?

Fear-based risk assessments, misinformation, and conspiracy theories.

Posted March 26, 2020 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

"Everybody knows that pestilences have a way of recurring in the world, yet somehow we find it hard to believe in ones that crash down on our heads from a blue sky. There have been as many plagues as wars in history, yet always plagues and wars take people equally by surprise."

“I have no idea what's awaiting me, or what will happen when this all ends. For the moment I know this: there are sick people and they need curing.”

—Albert Camus, The Plague

America is struggling to adjust to life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Across the country, social distancing is being inconsistently implemented and many are already growing restless, wondering whether we're over-reacting and when we should "open up" the country for business as usual again.

I discussed the differences of opinion over these issues with Cathy Cassata at Healthline.com for an article called, "Don’t Let These 5 Myths About COVID-19 Interfere with Your Safety." Here's the full transcript of that interview:

I wanted to start with a general question about disbelief. Can you comment on why some people may not think COVID-19 is serious and may be avoiding medical advice? Is it fear, feeling invincible, denial, conspiracy theories, or other reasons?

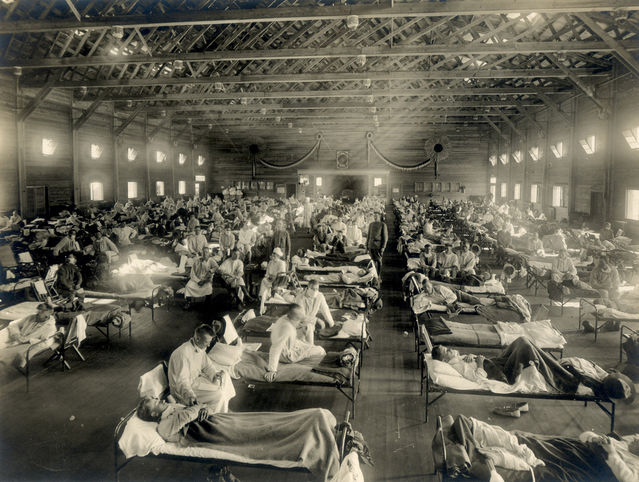

A pandemic on the scale of what a novel virus like SARS-CoV-2 could end up being has not occurred since the influenza pandemic of 1918 that took the lives of some 50 million or more people worldwide. Since few of us were around then, and given medical advances in the form of preventative vaccines and antiviral medications since that time, it’s hard for us to imagine that a “flu-like” illness could be so destructive.

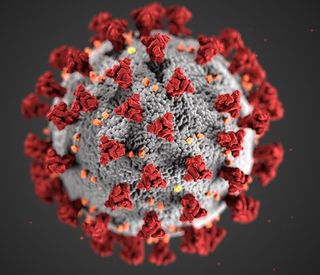

Together with the lack of established treatments for COVID-19 at this time, there are several basic scientific facts related to why SARS-CoV-2 may not be “just like the flu” such as how fast it spreads (its “RO”), its lethality, or its rate of mutation (see these articles at Vox, ProPublica, and The Atlantic for an explanation). But most of us weren't aware of these details in the earlier phase of the outbreak and with limited surveillance testing since then, those details are still being discovered.

“Optimism bias,” a general tendency that we all have whereby we tend to underestimate personal risks, is also a likely contributor. Optimism bias has been further fueled—especially in young people and healthy adults—by early data about the much greater risk of death from COVID-19 among the elderly or those with other "comorbid" medical issues.

Of course, such an attitude ignores the potential for SARS-CoV-2 carriers with mild illness and those who are asymptomatic to transmit it to people who are more vulnerable, which is a kind of narcissistic or self-centered perspective that's not unusual when we're young. So, there are many factors that allow us to discount risk during the early stages of a new infectious disease.

But some people continue to discount the risk of SARS-CoV-2 even now that there has been information from sources like the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) warning us that we should be very concerned, with large-scale social distancing as our best option to slow the spread and limit the worst possible outcomes. This can be explained by the fact that such information was initially contradicted by some political leaders here in the US who suggested it might be a hoax, such that differences in our level of concern about COVID-19 emerged across political lines, mirroring the same “debate” we see over climate change.

The current lethality of COVID-19 has been much more apparent than concerns about what climate change could do in the future however, making it a bit harder to deny the danger of COVID-19 as the pandemic spreads and the death-count increases. While we’ve seen conservative politicians including President Trump pivot, admitting that there is reason to be concerned and reinforcing recommendations for social distancing (or "distant socializing"), there's still a partisan divide along with a lot of misinformation out there about COVID-19 and counter-opinions suggesting that the economic damage associated with prolonged social distancing may be a “cure worse than the disease.”

And that’s where conspiracy theories come in. Some people who don’t trust the likes of the WHO or CDC and those convinced that liberals will do anything to ruin President Trump’s chances for re-election remain unimpressed by COVID-19's danger and instead adopt narratives about the media intentionally stoking COVID-19 panic in order to tank the economy for political reasons.

What makes people believe in conspiracy theories? I've heard some ideas, such as the desire for understanding and certainty; the desire for control and security; and the desire to maintain a positive self-image. Can you comment on any of these or add others?

There are many reasons why people believe in conspiracy theories (see my blog posts What Makes People Believe in Conspiracy Theories and Understanding the Psychology of Conspiracy Theories, Part 1 and Part 2 for a summary). Some of them are psychological, like the ones you mention.

But there are two things that should be emphasized when trying to understand conspiracy theories from a psychological perspective. One is that it’s normal for people to believe in conspiracy theories—about 50% of the U.S. population beliefs in at least one! The other is that there’s good evidence that conspiracy theories are rooted in mistrust. When people don’t trust authoritative sources of information—based on personal experience, political affiliation, or whatever—they are then vulnerable to misinformation.

And of course there is plenty of misinformation out there and plenty of places where conspiracy theories flourish, especially online. As I like to say, conspiracy theorists aren’t so much “theorists” as “theists” who find information that’s already out there and pick and choose what they want to believe based on preconceived notions and confirmation bias. And with the availability of abundant misinformation right alongside reliable information online, searching for answers on the internet becomes a matter of “confirmation bias on steroids.”

Why do conspiracy theories resonate with people? Is it because they take something out of context and present it as truth? For example, one conspiracy theory related to the novel coronavirus that we are seeing people holding onto is that there's "a disease every election year," which is not accurate.

The idea that there's some hidden truth behind world events always seems to have a certain appeal. When somebody believes they're privy to that hidden truth, unlike the rest of us "sheep," it appeals to what psychologists call a "need for uniqueness." And fictional narratives are often more tantalizing than the mundane truth or the reality that things, and especially terrible things, often happen for no apparent reason.

But it's also important to realize that conspiracy theories can arise due to deliberate misinformation or disinformation. Disinformation is a well-known tool or weapon of politics that has traditionally been associated with authoritarian regimes like Russia (see Illusory Truth, Lies, and Political Propaganda, Part 1 and Part 2 for a review). But it’s increasingly used throughout the world, including here in the US, to achieve political ends.

Some have argued that the intent has been to get people to lose faith not only in institutions of authority, but to lose faith in the very concepts of truth and trust, such that we now live in something of a “post-truth” world. With so many of us mistrusting our political or ideological opponents, we tend to see everything according to the kind of ulterior motives and political machinations that form the basis of conspiracy theories. These days it seems there’s often an “us and them” version of almost every national narrative, including COVID-19.

Is there anything else you'd like to say about why people may not believe the seriousness of COVID-19 or anything else about conspiracy theories?

In general, conspiracy theories aren’t really any more common on one side of the political fence. Likewise, we all have cognitive biases related to risk assessment—under some conditions we tend to under-estimate risk (like with COVID-19 based on the factors discussed above), just as we sometimes tend to over-estimate them (like with fears of infrequent, but catastrophic events like airplanes crashing). It's theoretically possible that we’re over-reacting to COVID-19, particularly as we mull over just how long strict social distancing should be maintained.

The prevailing consensus from public health scientists, epidemiologists, and infectious disease specialists is that drastic measures are warranted in order to “flatten the curve” and minimize the impact—especially the number of deaths—related to COVID-19. From that perspective, given the potential for as many lives to be lost as in 1918, erring on the side of overreaction makes complete sense.

But the reality is that such unprecedented social distancing will indeed have potentially catastrophic effects on the economy the longer it continues. How we weigh the risk of mass casualties against the risk of economic disaster is something that we’ll likely hear opinions and debates about for the foreseeable future.

For more on COVID-19:

► Disregarding Science: The Politics of COVID-19 Beliefs

► From Angst to Ennui: Adjusting to Life During COVID-19

► COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories: Was SARS-CoV-2 Made in a Lab?

► The Deadly Effects of COVID-19 Misinformation