Extroversion

Why Extraverts Talk So Much

The external world is their internal world.

Posted October 1, 2021 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Introverts thrive on an inner life of the mind and gain greater self-awareness through introspection.

- Extraverts, on the other hand, need other people to think and function optimally.

- Socializing with others is the means by which extraverts come to better understand themselves.

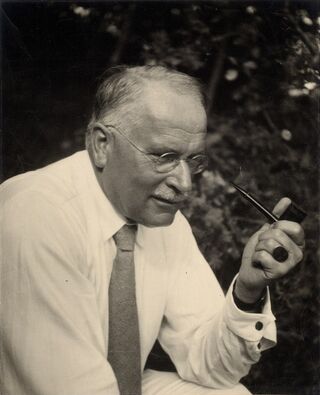

Carl Jung offered the world his typology of extraversion and introversion in his book Psychological Types. Jung’s explanation of these types conveyed them as styles of perceiving, processing, and directing mind energy, with one type no better than the other.

Jung preferred the term “psychic energy,” though he sometimes used “libido,” a term re-appropriated from Freud to mean, rather than merely sexual energy, energies of the mind or even soul—innate psychogenic activity inexplicable by natural laws.

Here is the looming question: Why is it that extraverts talk so much?

In Jung’s descriptions, an extraverted person’s attitude of consistently directing their mind’s attention and energies to the human activity of their immediate world is so directed in order to function.

While introverts functionally and routinely retreat as their ego defenses shield them from a world of hustle and bustle and a world of people (extraverts, mind you) that won’t stop talking, the extraverts double-down on their boisterous social instincts as if survival depended on it.

As I border on the heresy of typecasting extraverts as gregarious and introverts as shy, I distract from the ancient enigma Jung brilliantly clarified when he deciphered the behavior of extraverts in their verbal explorations as psychological energy directed externally, primarily toward other people. In fact, Jung said that for extraverts, the world of other people is an inexhaustible fascination tempting them never to look for anything else.

For an extravert, the world of other people is the inner world.

In an ecological sense, we are all interconnected. In Mind and Nature, the pioneering social scientist and cyberneticist Gregory Bateson emphasized the need to extrapolate patterns of mental processes alongside patterns of adaptive processes—all forms of communication have an adaptive function, and perception is nearly inextricably tied to processes of communication.

Extraverts have more need to communicate to adapt. In other words, extraverts verbalize and then are better able to process how to respond to their environment, depending on how objects of their verbalizations react. This brings to mind the adaptive function of bats sending high-frequency sound to reverberate off objects in their environment in order to calculate when and where to swerve. Extraverts’ minds have a greater functional reliance on social stimulus than introverts’ minds.

Introverts, on the other hand, focus their mind’s energy primarily within. Their sense of self adapts within an internal world behind protective fencing, occasionally encroached upon by raiders, invading armies, or, more likely, friends and colleagues, neighbors, and loved ones.

At the opposite extreme, extraverts adapt to the human energies outside of them and move about among other people sometimes as if the other people were an extension of their own consciousness, as if they best experience the fullness of themselves in the light cast by human relating.

Interpersonal feedback acts as a psychological grounding for the lightning energies of extraverts. Jung instructed: “Extraverts’ subjective attitude is constantly related to and oriented by the object.” This practically answers the question at hand. Extraverts talk it out to think it out.

Extraverts need others to think optimally. Jung contrasted extraverts determining essential decisions and actions in their orientation to “objects” (a term which includes but is not limited to other human beings) from introverts basing decisions and actions on subjective values.

It would be short-sighted to limit this adaptive function to thinking.

Jung wrote that extraverts modulate their own attitude in relating to others and that they give extraordinary attention to the effect they have on others. Introverts tend to modulate attitude to others, too, but do so in a more protective rather than exploratory mode, generally.

For extraverts, Jung observed, “Fear of objects is minimal; he lives and moves among them with confidence.” Verbal exploration is an information processing function and, even more vitally, a human energy management function—in that, while introverts need to protect from energy loss incurred through verbal contact with others, extraverts at an intrinsic level need the energy that human verbal relatedness affords. Yes, introverts need relatedness and belonging too, yet extraverts need not only intimate friendships but even continual personal encountering of the unfamiliar.

Jung contended that, for extraverts, “Everything unknown is alluring.”

The world around extraverts is their psychological space. Therefore, they occupy it to experience it and, in so doing, they experience themselves.

Facebook/LinkedIn image: GaudiLab/Shutterstock

References

Bateson, G. (1979). Mind and nature: A necessary unity. New York: Bantam.

Jung, C. G. (1971) [1921]. Psychological Types. Collected Works of C. G. Jung., Volume 6. Translated by Adler, Gerhard; Hull, R. F. C. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.