Play

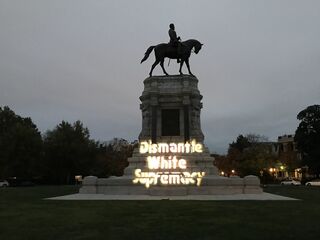

We Do Not Concede, Nor Do We Condemn (Part 3)

Part 3: Chronicling the fight against white supremacy and radicalization.

Posted January 15, 2021

This post concludes a three-part serialized excerpt of an interview with Life After Hate CEO Sammy Rangel that originally appeared in my book, Leadership: Performance Beyond Expectations. In this excerpt, Rangel discusses the role that we all play in shaping our communities, and in the need to honor humanity in even the ugliest of behaviors.

Addressing Criminogenic Needs

‘Criminogenic needs’ need to be addressed—because if you get someone sober who has a criminal personality, all you then have is a sober criminal. If you get someone stable on their medication, all you get is a criminal who is stable on their medication. An addict personality might separate from empathy out of shame—like, ‘I’m not worthy to engage,’ or maybe they experience physiological motivations to feed a physical addiction that over-rides their higher-level cognitive functions (such as empathy). Compare that to the criminal personality—criminality involves a disregard for other human life—so criminal personalities just don’t feel empathy. We have to understand these two groups separately.

Why Don’t People Leave Extremist Groups?

Why don’t people leave white supremacy groups when they realize it’s a bad path to take? Well, why don’t people lose the 5 pounds they’ve been trying to lose all year? We all maybe have a burning motivation to make a change but being able to actually see through that change is monumental. Monumental.

Our society is very judgmental. If you take my personal story and see what I did as a child, how violent and aggressive I became as a child, after people hear my story, the typical audience member says that they understand why I did what I did. That doesn’t mean they say it was OK, or that what I did was justified. It means they understand the evolutionary process, that there were other forces at play. Sadly, our society doesn’t want to admit that we play a part in creating this subculture of our community—but we all do.

Recidivism and Reform

Here in the U.S., we think that if you deal with drugs and alcohol then you deal with criminality. It’s not that simple. In fact, I read a recent study where it shows that if you get someone stable on medication and sober and get them a job—the "big three," as these factors were formerly known (the goals of re-entry), it still doesn’t move the needle on recidivism. Recidivism rates stay the same.

I’ve just been able to convince the state of Wisconsin that the state itself contributes to recidivism rates. In Wisconsin’s previous re-entry program, which was seen as successful, recidivism rates were 26% in year one. By year three, recidivism rates went up to around 60%—high, but still better than the state average. We hit a 6% recidivism rate for the program that I designed for them in years one, two, and three of the program. And we’d lowered the revocation rate for sex offenders by 75% by the end of the three years, too. Those were the same men and women that society would say, "If they wanted to change, they would change. They obviously don’t want to." We have all these reasons why we can justify why they fail—but until we say we play a part in the failure rate, we won’t change it.

We Do Not Concede, Nor Do We Condemn

Life After Hate remains the one and only entity in America right now who is telling a white supremacist that this is a safe place for you if you want to talk. Everyone else is saying, "Not in my town, buddy—get the hell out." Since Charlottesville alone, we’ve helped over 350 individuals. It’s not that I think these former white supremacists are victims. We create a space where we can address specific issues. Life After Hate’s unwritten position is we don’t call people out, we call people in. It’s a very hard road to walk in the face of what we are dealing with but it’s really the secret sauce behind what we are doing. We are honoring the humanity in even the ugliest of behaviors—there is a person behind those behaviors. And what we ask ourselves is can we reach beyond that behavior and touch the person? That is what we try to do.

I think as an educator or family member, you don’t need to concede, but you don’t need to condemn either. We aren’t conceding anything by listening to these people. But we also don’t feel the need to condemn them. What I’m most proud of personally is the fact that my children see their dad fighting for the civil rights for all people, including those who would condemn us. I think ultimately the most important message is to recognize that no one is broken beyond repair, people are, with the right approach and the right spirit, just about anything becomes possible.

Honoring Grievances

My violence was my voice because I lived in a world where no one listened. I know that about myself now. I’ve been out of my gang well over 20 years now, so I don’t feel at risk of going back—but I can tell you that in the beginning days and months, I felt like that was the only alternative. Because there’s a lot of fear to change, a lot of uncertainty.

I mean, I had never been to a supermarket because I’d been incarcerated for a long time. Aged 30, I went to a grocery store called Woodman’s—it’s like a mall, a huge store, tens of thousands of square feet large, with 50 different types of vegetables I’d never seen. I reached in for a vegetable that first day out of prison and the water sprayed out of it and it scared the s--t out of me! While I can laugh about it today, in that moment it was deeply concerning to me—like, what else could be waiting to jump out at me? If I can’t even deal with that, how will I cope with the big stuff?

People can get triggered, too. We see the elections, maybe shootings … then the old thoughts pop up. But when they are surrounded by us, by Life After Hate, we can tell them, it’s not unusual for us to have those thoughts, brother. It’s okay. Just know that’s not where you are at today. We can coach people through that. People can reach out to us without judgment. We are only here to talk and listen. We encourage them to reach out to us, and you never know what can happen in the conversation, especially with people who have been down that path and take a position of compassion and empathy as a principle.

After Charlottesville, national media picked up our story, and publicized the fact that the Trump Administration had reversed our funding. The media spread the message that we were the only group in America trying to fight the issues that lay behind Charlottesville—and we went viral quickly thereafter. I think we raised almost $1m in a couple of months.”

Life After Hate remains one of the only organizations committed to the rehabilitation and reintegration of white supremacists into mainstream society. At a time of monumental political upheaval, with the specter of domestic radicalization remaining an ongoing threat, their work has never been more vital.

Find Out More