Anger

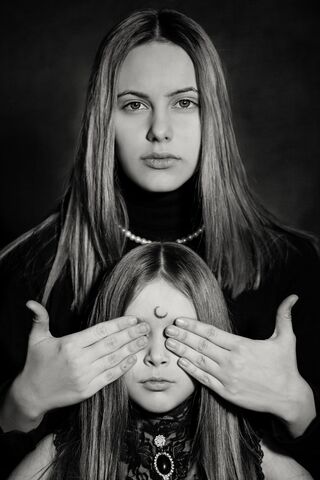

When a Parent Needs Too Much

An enmeshed parent/child relationship can be harmful to both.

Posted March 31, 2021 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Parent/child enmeshment can be difficult to identify, as it can resemble and even feel like a close, healthy relationship.

- The parent is overly reliant on their child, perhaps as a confidante or as a focus that can help them avoid or distract from their own unhappiness.

- Enmeshed children can live a strange dichotomy of feeling special, while never developing their own self-reliance, confidence, or ability to set healthy boundaries.

Being a parent is a complicated job.

All parents are going to make mistakes that impact their children. It's one of the terrifying realizations you make very early on. They'll benefit from your strengths... but your vulnerabilities will also affect them.

Right before my son was born, I realized that I knew I'd been a good-enough mom while I was pregnant. Not too much fast food (although I was amazed he didn't come out looking like a chicken nugget...) and plenty of rest. Things got a lot fuzzier when he was a babe in arms.

This parenting gig is humbling.

Yet, some problems are harder to see than others. What's one of them? When a parent needs too much from that child—or, as psychology calls it, enmeshment.

What is enmeshment?

Enmeshment means just what it sounds like—the boundaries between parent and child don't exist clearly, if at all.

One parent shares too much; another one lives through a child's success. A child gets the message that it's not OK to be independent. Instead, you're expected to be a parent's confidante. Your life isn't your own. It might never occur to you not to include your parent in your daily comings and goings or even your decisions.

What's tricky about this? It can appear from the outside that all is well—that this is what family closeness looks like. In fact, friends might say, "You've got it so lucky." But on the inside, the parent expects constant communication as their child fills a void that perhaps they understand. Or perhaps they don't. As the "child," you can be stricken by guilt for simply desiring your own life—as if you're not appreciative or grateful for their love.

What's the danger of enmeshment for both the parent and the child?

Children can't fix an adult's unhappiness. Your problems are adult problems and can only be truly healed by your own actions. Continuing to focus on your child's life might prevent you from going to a therapist to see what's truly wrong or why you need to be so involved in your child's life. What would need to happen to confront whatever is wrong in your own partnership or marriage that has been long denied or ignored?

What about if you're the child? You fail at this important role you're playing. To fix that? You must try harder to please. And that can turn into a lifelong job.

The wounds of enmeshment for the child

Dr. Pat Love wrote a book about this phenomenon called The Emotional Incest Syndrome: What To Do When A Parent's Love Rules Your Life. She describes the cost to the child, “If the parent represses the girl's (or boy's) anger not just once but over and over again, a deeper injury occurs: the girl will eventually dismantle her anger response. Ultimately, it's safer for her to cut off a part of her being than to battle the person on whom her life depends.”

There's the setup for perfectionism and depression. You begin to feel that your life should be devoted to the well-being of that parent. And you better be really good at it—or something bad could happen.

Dr. Love's point? In order to emotionally survive, you cut off the anger as you feel more and more pressured to meet the expectations of the parent on whom you depend—at least as a child. And even shame yourself for any feelings of resentment that might try to seep into your awareness.

Enmeshment also sets up a long-lasting sense of low self-esteem. Its irony lies in its superficial creation of the child feeling special while, at the same time, inherently creating tremendous self-doubt. This can easily lead to a lifelong questioning of your decision-making ability or ability to soothe your own distress. After all, your parent has always been there, and your continuing enmeshment with them may lead to not knowing what to do to help yourself feel better, no matter what the situation. And you'll likely avoid conflict with others and even become what's called a people-pleaser, not knowing how to set healthy boundaries.

The parent's message, perhaps unintentional, is, "You can't really do life well without me." Yet sometimes, in fact, the message is intentional... and manipulative. If so, the child will likely never get permission to step away and may even be punished for doing so.

Breaking the patterns of enmeshment...

Yet when the lights start coming on, the realizations about enmeshment can become very clear.

"I never realized that I don't make a decision without talking to my mom about it first."

"I just assumed that I would help with my dad's business. I never gave one thought to doing something on my own. So, what now?"

The good news is that this dynamic can be changed. Parents who've been able to see what they've unintentionally done can decide to back off for everyone's well-being, support their child's individuality, and seek more appropriate friendships or even therapy. Adult children who needed to pull away from the intensity of the relationship can slowly step out of the enmeshment, dealing with their own self-doubt, and learn how to set boundaries of their own.

It will feel odd for a while. There will be space where there was no space before. It can feel lonely—perhaps, oddly enough, for both of you. If you're the parent, finding other relationships that can support you is the first line of business, so you're far less reliant on your child. If you're the adult child, you may have become quite accustomed to the parent's constant contact, and being without it can feel a little shaky. So your task is to build your own sense of identity while learning to share in other healthy, supportive relationships.

And both of you can know that your love and support for one another is freely given, but also is respectful of your own individual identities.