Sport and Competition

Are You at Risk of Misplacing Yourself?

Overplacement is the exaggerated belief that we're better than others.

Posted April 30, 2020 Reviewed by Matt Huston

In 1953, General Motors accounted for roughly half of automobile sales in the United States. At the time, it was the largest corporation in the United States. GM CEO Charles Wilson famously said he believed that “what was good for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa.” Imported vehicles accounted for less than 10 percent of US market share and GM did not perceive much of a threat from Japanese rivals.

The managers and workers at GM were proud of their status, even haughty. As Japanese auto makers slowly gained ground, improving their quality and market share, GM failed to take the threat seriously. The company dismissed reports that Japanese cars were of higher quality, even claiming that observers like Consumer Reports were somehow biased against them. In the 1980s, when GM collaborated with Toyota on a joint venture, it got a glimpse inside the Toyota production system that allowed Toyota to produce cars less expensively and with fewer defects. Yet GM failed to capitalize on these insights, even as its rivals gained on it. Today, GM accounts for less than 20% of domestic American auto sales. Imports account for more than half.

It is common for people to be overconfident about their superiority relative to others. When I ask my MBA students to rate themselves relative to one another with regard to intelligence, attractiveness, honesty, and skill, they routinely rate themselves above average. Actually, what I do is ask them to rate themselves on a percentile scale, which estimates the percentage of the class that is worse than they are. A student who gives himself a percentile ranking of 0 on intelligence indicates that he thinks he is the least intelligent person in the class. A rating of 100 would imply he thinks he is the most intelligent. If the entire class agreed on what it meant to be intelligent and how intelligent each of them was, then the average would have to be 50. In fact, the averages of the percentile rankings my students give themselves are usually closer to 65. The majority of the students claim to be better than the median, which is a statistical impossibility.

Every day we size ourselves up relative to competitors. Should I start a new company? Should I enter a contest? Should I challenge a rival? We recognize that the choice of whether to launch a business, submit an application, or run for elected office depends on how we stand relative to those rivals.

But we tend to make systematic mistakes when assessing our potential relative to the others. Many of us go through life believing that we are better, more virtuous, and more deserving than others. This is what the researchers call overplacement, because we place ourselves higher, relative to others, than we actually are. When we act on these overconfident beliefs in our superiority, we can easily get into trouble.

For instance, most new businesses fail. In many industries, as many as 80% of new startups are out of business within five years, and that rate of failure has leapt up recently. If entrepreneurs are perfectly rational, it is hard to explain the perennially high rate of entry if they have accurate beliefs about how good they are. Successful entrepreneurs like Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg get a great deal of media attention, but their success represents the exception. Politicians talk of small businesses being the source of job creation in the United States. It is also true that small businesses are responsible for a tremendous amount of job destruction. They come and go so much that they churn through lots of employees.

Overplacement is one viable explanation for persistent high rates of entrepreneurial entry. If potential entrepreneurs are convinced that they are better than their potential competitors—that they are the exception to the rule when it comes to entrepreneurial success—they will continue to start new companies despite the low probability of success.

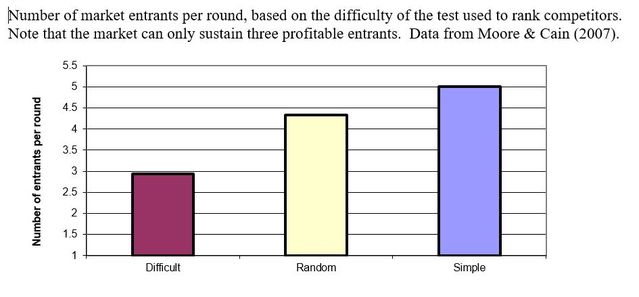

I have run market experiments in my research lab in which participants have the choice of whether to compete. If the market can only support three profitable entrants, it is common to see seven people rush to compete. I see this situation most often when people feel confident about their capacity to outperform the competition, such as when the task at hand appears easy.

In some of my laboratory markets, for instance, market entrants are ranked based on a simple trivia quiz with questions such as, “Who crossed the Atlantic Ocean in 1492 and ‘discovered’ America?” Feeling confident about their answers on the quiz, too many people entered the contest, and the majority lost money.

But the contest played out quite differently when we picked harder trivia questions, such as, “What were the names of the three ships Columbus used in his 1492 voyage to the Americas?” When the task was harder, people believed that they had done worse than others. As a result, fewer people entered the contest in these rounds. Consequently, entrants in these “difficult” markets were more likely to win. The average entrant made money.

When people knew they would be ranked randomly relative to other entrants, we did not observe much bias in people’s beliefs about their rankings.

Sometimes, as in the difficult markets, we are liable to make the mistake of thinking that we are worse than others when we are not. This happens, for instance, when our own shortcomings are particularly visible to us but others’ inadequacies are not. I know, for instance, how easily I am distracted when I am trying to write. When I find myself staring at a blinking cursor, unsure what to write next, suddenly checking in on Facebook and Twitter seem terribly urgent. Nothing interesting there? Then maybe it is time to search Google Images for pictures of aging child movie stars to see what they look like now. Then over to YouTube to see what new videos have been posted in the last 10 minutes.

What is not so obvious to me is how easily other writers are distracted when they try to write. I’m tempted to think that they can’t be any worse than I am. However, before I come to any such conclusions, I really ought to acquire information about them. It is possible that other writers are worse than I am—at least I haven’t visited my profile on HotOrNot.com yet today. Or, more likely, if I gather more systematic evidence, I will learn that I am near the median, despite my deep desire to believe that I am special and unique. Here, as elsewhere, wisdom councils that I should pay attention to the evidence about my own standing relative to others.

So before you decide to launch into any competition, or before you decide to withdraw from any competition, whether in business, love, or life, it pays to collect good information about how you stack up. Do not let your decisions be driven by your hopes or your fears. Collect good data to help you assess the risks, whether the risks be business failure or exposure to the novel coronavirus.

References

Moore, D. A., & Cain, D. M. (2007). Overconfidence and underconfidence: When and why people underestimate (and overestimate) the competition. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 103, 197–213.