Happiness

Why Much of Psychological Research Isn’t About You

Psychological research is about an average person, not you or me.

Posted June 16, 2021 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- It may not seem too much to ask that psychological research findings help us understand individuals like you and me. But generally they don’t.

- Typical findings describe an abstract average person who is far removed from any actual individual.

- Psychologists working with individual people can help them, but they don’t have to care about the average person.

Knowing I’d graduated with a psychology degree, people started asking me questions like what to do with a difficult child or how to understand their partner's oddities. I had no clue what to say, beyond what I felt any observant person, psychologist or not, could say. I told them as much, and soon they stopped asking.

Someone with an engineering degree can tell you how a device works, because they understand its working principles or at least how a prototypical device of the kind works. But faced with questions about the feelings, thoughts, motivations, or behavior of particular individuals, psychological researchers often have no better answers than someone without a degree. This is because:

- human minds are highly complex;

- people are different; and

- psychological science is mostly about an abstract average person who is an unfaithful representation of actual individuals.

I am not suggesting that psychological science is headed in a wrong direction. I think were are accumulating a solid body of knowledge about the average person and that this focus is right because science ought to be about universals – here, what generalises across individuals. But we have to be honest about what this science can offer: it is a psychology of the stranger, not a psychology of any actual individual you or I know.

Neither am I suggesting that psychologists working with clients don't know what they are doing. A therapist’s job is to help individual people to develop useful working models of why these individuals, given their unique experiences and skills, do what they do, so that they could change if and how they need. To achieve this, therapists and their clients don't have to care about whether their working models comply with the average person that emerges from psychological research.

Associations are small

The reason why I write about this now is that there is a transition happening in psychological research.

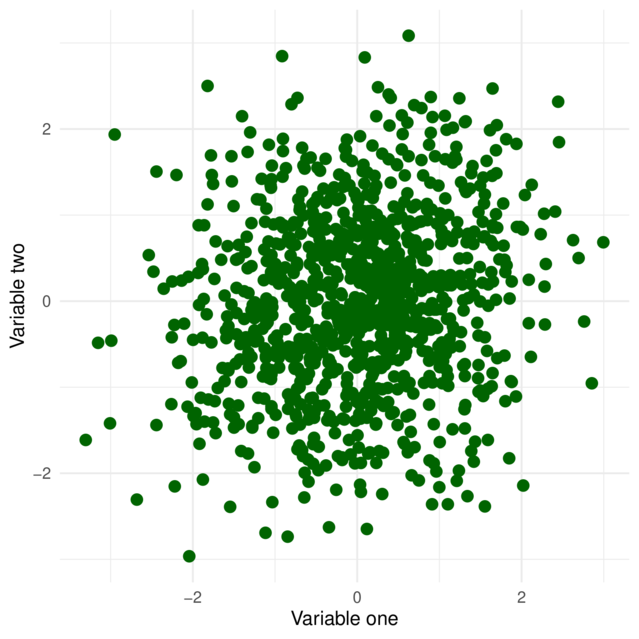

Psychologists learn about humans by exploring associations between variables like happiness or what people see in their visual fields. The associations worth exploring – some are too trivial to even study, like feeling sad after having lost somebody you are close to – do not just present themselves. Instead, they are often invisible to the naked eye. To see them, researchers have to collect data from hundreds or even thousands of people, amplifying what is common in them (the signal) and filtering out the rest (the noise, for this research purpose).

Researchers call the ratio between signal and noise an effect size, which can vary from nothing (no signal here, sorry) to very strong. For example, correlation coefficients can vary from 0 to 1.

Until recently, though, many researchers treated the effects in an all-or-nothing manner: An association either was there or was not, the technical term being "statistically [not] significant". Money either made people happier or it didn't. It is only recently that the whole field has started taking effect sizes for what they actually are: degrees of association strength, from very weak to very strong.

And one particular result of this transition is beginning to sink in: the effect sizes are typically small. Often very small. In the metrics of the correlation coefficient, the most typical effect sizes are somewhere around .20 (see here or here) and many are smaller still.

For example, the correlations of childhood physical and sexual abuse with later depression are around .10 and .20, as are the correlations between aspects of relationship quality and happiness. The widely discussed correlation between growth mindset and academic achievement is around .10, whereas the correlation between low self-discipline and high body mass is about .06.

What do such small associations mean?

Suppose we have two variables with a typically-sized correlation between them — say income and happiness — and that we can assign people into three equally-sized groups in both of them: low, medium and high. Knowing that those on high income are on average happier than their less-earning peers, you could reasonably expect that an individual with high income is likely to have high happiness as well.

But you would be wrong nearly three times out of five: Rather than enjoying high happiness, a high-income person is statistically more likely to have either low or medium happiness. For your expectation to be true even half of the time, the income-happiness correlation would need to be at least twice as strong as it actually is. And not many associations are that strong in psychology.

What is more, the happiness of someone with medium income would be even less predictable because of a statistical phenomenon called regression to the mean. In fact, a person with a medium income is almost equally likely to fall into any of the three happiness groups – despite that robust average trend for happiness to increase with income.

So, for the abstract average person, high income is a good thing as far as their happiness is concerned. But for the happiness of an actual individual with an average income, money is pretty much irrelevant, statistically speaking.

Why are the associations so small?

Associations may be small because many variables are causally involved in each and every thing that people do. For example, hundreds of little reasons can gradually nudge a person toward a decision to divorce.

Or associations may be small because people are genuinely different and have unique reasons for doing one thing or another. For example, someone may want to divorce their husband for one single reason such as his snoring, but another person may come to the same decision for a completely different reason.

Most likely, however, both scenarios apply: There are many reasons involved in any one thing that people do, and people also differ in these reasons. In statistical analyses of large groups of people, some of the reasons wash up as small effects describing the average individual.

Small effects can be practically useful

To be fair, even very small effects can be practically useful.

For example, even though the protective effect of aspirin on the probability of developing a heart attack is very small – that is, it may be somewhat useful for a small fraction of people – giving this cheap drug to thousands of people can save many lives, even if it does nothing for the vast majority of people. Likewise, effects found in psychological research, even if small, could often be put into use to help some people.

But this is beside the point. I argue that we cannot connect the small probabilistic associations that we can extract from large groups of people – pertaining to the abstract average person – to what happens to a particular individual. Even if Aunt Dorothy takes aspirin and does not get a heart attack, there is no way we can say that it is the drug that is saving her.

Where does this leave us?

This may sound like bad news, but I prefer to think of it differently.

If it turns out that people are psychologically even more complicated and unique than we thought, then we have to accept it. And not only that, we can marvel at the flexibility and uniqueness of the human mind, underlain by approximately 100 billion neurons and 100 trillion ever-changing connections between them in each brain. This richness and unpredictability of the human mind and behavior may well be some of the main things that make our lives enjoyable.

And even if the average person that psychology is busy describing is far removed from most actual individuals, this does not make the research findings meaningless. What we can learn from them can offer us intellectual and aesthetic satisfaction, just like learning about the beginning of the universe can. Besides, some findings may eventually be put into use in population-level interventions.

But the flip-side of knowing could be just as important: Learning about what we cannot know, even in principle, can be used to rein in unfounded ideas. It may be that psychologists are often most useful using their knowledge to say: “Hey, we don't know and even cannot know why something happens in individuals based on a handful of universal and intuitive laws”. Because even where these laws exist, they are too numerous and too probabilistic to apply to actual individuals.

So, next time you hear a simple explanation for someone’s behavior, beware. Unless the explainer knows a great deal about the specific circumstances of the individual in question, perhaps relying on “recent research” instead, he is more often wrong than right – even if he happens to be a psychologist.

A good psychologist is not afraid to say that she doesn't know – and often even cannot know.