Leadership

The Winter War Ghost Haunts Putin's War Today

The Russo-Finnish War was a near-disaster for Stalin, presaging Putin's war.

Posted March 11, 2022 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Putin's war against Ukraine has some notable parallels with Stalin's war against Finland.

- In both cases, the invader over-estimated its own armed forces and under-estimated those of their victim.

- Stalin thought he would win easily, and the world agreed. Putin thought he would win easily, and the world agreed.

- Despite many such similarities, it isn't clear whether the Russo-Finnish War of 1939-1940 predicts the outcome of the current Russo-Ukraine War.

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Attributed to George Santayana, this famous observation has special resonance today, as Russia struggles to subdue Ukraine, having apparently forgotten its past, lamentable efforts to subdue another, even smaller neighbor: Finland.

There are some remarkably convergent parallels between the 1939-1940 Russo-Finnish War (also known as the “Winter War”) and the current war in Ukraine. Little remembered these days outside Finland, it offers a cautionary tale that Putin doubtless already knows—but has ignored—as well as a possibly optimistic foreshadowing of what might yet happen.

Stalin claimed that Finland could be used as a staging ground for an attack on his country. (Sounds familiar?) After all, the Russo-Finnish border was only about 20 miles from Leningrad, now St. Petersburg. He ordered his military to attack tiny Finland, assuming that it would be a walk-over, completed in at most a few days. (Sounds familiar?) The rest of the world agreed, with essentially nobody giving the Finns a chance. (Sounds familiar?) “The Finns are putting on a good show,” noted the renowned English historian and diplomat Harold Nicholson, as the Winter War was barely 48 hours old, “but they will collapse in a day or two.” This was also the overwhelming worldwide consensus, but the Finns evidently hadn’t been told of their imminent demise.

From here on, I’ll stop italicizing the many convergences between Stalin's Winter War and Putin's Ukraine War, trusting that you, dear readers, will have no difficulty recognizing how the two historical shoes fit.

In 1939, the USSR’s population was about 175 million; Finland’s, fewer than 4 million. The Finns had essentially no heavy weapons: no tanks, not even anti-tank weapons, no anti-aircraft guns, no large-bore artillery, and hardly any combat aircraft. Stalin attacked with “just” four of his armies—about 500,000 men—keeping the rest in reserve. The Finns fought back with all they had: Lightly armed military manpower of about 120,000.

Ukraine currently has a bit more than 200,000 soldiers, Russia 900,000. Russia has huge manpower reserves, Ukraine much less. Russia has more than three times Ukraine’s battle tanks, and ten times its military budget. Like today's Ukrainians, the Finns had a fierce love of their country, and the courage and skill to defend themselves. They were fighting for their homes and their families, on terrain that they knew well. The invading Soviet troops were almost entirely unwilling conscripts, with little motivation or knowledge of why they were supposed to fight.

Some international volunteers (a bit more than 10,000) joined the Finns. But the Western countries did essentially nothing, concluding that theirs was a lost cause, and not wanting to antagonize Stalin. The American people were very sympathetic to tiny Finland and President Roosevelt successfully maneuvered to provide them with a dozen Brewster Buffalo fighter planes—so outmoded that the American pilots, who just a year later found them lethally outmatched by Japanese Zeros, called them “flying coffins.”

Finland had been part of the Russian Empire since 1809, although it retained its language and fierce nationalistic pride despite ongoing tsarist efforts to “Russify” it. Immediately after the Russian Revolution, in 1917, Finland finally managed to declare independence. Nonetheless, in 1939, Stalin was confident that he could reincorporate it into mother Russia and that he’d be welcomed by the local population. Was he wrong!

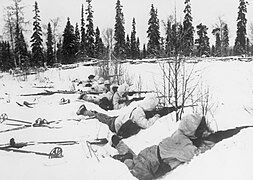

In addition to having talked himself into devaluing Finnish nationalism, he had woefully over-estimated the prowess of his own army while disastrously under-estimating that of the Finns. Highly motivated Finnish ski troops, often camouflaged in winter white—and labeled “ghosts” by the increasingly despondent Russian invaders—wreaked havoc on the Soviet forces, using rifles and machine guns, and making quick, devastating hit-and-run attacks on the invaders’ lumbering columns. One Finnish soldier, Simo Hayha, became the most successful sniper of all time, with allegedly more than 500 kills.

The Finns also used a surprisingly effective home-made weapon, which had been originally improvised during the Spanish Civil War, but memorably named during the Winter War, after People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov announced to his domestic audience and the disbelieving world, via radio broadcasts, that the Soviets weren’t dropping bombs. Rather, they were on purely humanitarian missions, providing food to the hungry Finnish people. The Finns satirically called these bombs "Molotov bread baskets," before labelling their now-famous bottles, which, filled with flammable liquid, served as a kind of poor-man’s anti-tank hand grenade, “Molotov Cocktails.”

Stalin had woefully misjudged the effectiveness of his army, as well as the capability and spunk of the Finnish defenders. Eventually, however, Carl Gustav Mannerheim, the Finnish leader, had to sue for peace, after his country had held out against the Soviet goliath for an astounding 140 days, during which time he had begged for U.S. troops, to no avail. But Stalin also recognized that he, too, couldn’t really win, and even if he did in the short term, continuing to subjugate Finland would be dauntingly difficult, if not impossible. So, a deal was reached whereby Finland gave up about 9 percent of its territory, notably some in the far north and most of the province of Karelia, whose residents overwhelmingly evacuated to the country’s south.

The Finns had lost approximately 25,000 troops; the Soviets, roughly 250,000. Although Finland eventually gave in, it was not before they had achieved one of the most notable defensive actions in human history, comparable to Masada and Thermopylae. Moreover, the performance of the Soviet Army was so poor by comparison that it revealed Stalin's military to be much weaker than had been widely thought, which appears to have encouraged Hitler to take seriously his own invasion plans, which he acted upon roughly a year later.

Alas, when Hitler did invade the USSR, Finland tarnished much of its deserved glory and international support by allying itself with Germany—almost entirely out of fury at the Soviet Union, and hoping to regain the territory lost to Stalin.

Stalin had called his invasion of Finland a “liberation operation,” while Putin claims that in Ukraine, his forces have been carrying out a “special military operation.” He has gone further, announcing that his goal is to protect ethnic Ukrainian Russians, and to cleanse Ukraine of its "drug-ridden, Nazi leadership."

There have been some notable recent cases in which a supposed superpower failed in trying to subdue a much smaller adversary: For example, the Soviets in Afghanistan, and the U.S. in Vietnam and also in Afghanistan.

It is by no means inevitable, however, that Goliath fails when battling David. Consider the U.S. vs. Mexico, or Spain, and its regular subjugation of many Latin American countries, just as Russia successfully overwhelmed the Hungarian Freedom Fighters in 1956, the “Prague Spring” of 1968, and the Baltic states after World War I, as well as Chechnya and Georgia during Putin’s reign. There is also no guarantee that Russia’s past, vis-à-vis Finland will be a prologue for its current war against Ukraine. But Santayana’s warning may yet stand as a prophecy that Putin ignores at his peril.

David P. Barash is professor of psychology emeritus at the University of Washington. His most recent book is Threats: Intimidation and its Discontents (2020, Oxford University Press).