Chronic Pain

Chronic Pain Is an Over-Determined Survival Response

Understanding how pain is experienced can lead to better care.

Posted October 21, 2018

In an earlier post, “Chronic Pain Is Not a Disease,” I disagreed with the Institute of Medicine’s idea that chronic pain is a disease. Here, I propose another way to think about chronic pain. I think of pain as a survival response gone awry. Understanding the brain’s mechanism for experiencing pain and constructing emotions helps to understand this point, which is particularly important because it has ramifications for treatment.

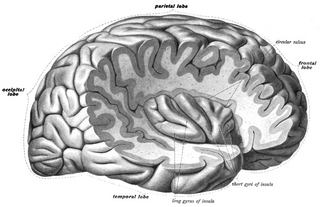

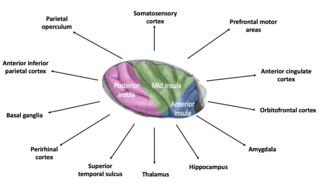

Initially, the posterior part of the insula (see pictures) processes these sensory inputs as subconscious body sensations that have little or no emotional component. These sensations are soon re-represented, however, in the mid-insula and then in the anterior insula to become subjective, emotion-based sensations. If strong enough, they become felt emotions—such as sadness or joy—as they interact with the anterior cingulate, prefrontal cortices, and other areas.

How do simple physical sensations become linked to emotions? (Who hasn’t noticed their heart beating when they are suddenly frightened?) Emotions go hand-in-hand with physiological changes throughout our bodies. This change occurs because the bottom-up sensory input to the insula is modified by top-down input from the motivational, rational, and cognitive dimensions of many higher brain regions (see picture). Linking this extensive overlay to the physical sensation produces emotion, thus providing an awareness of the body in terms of emotions and related thoughts.1-3 Often engaging the somatosensory and anterior cingulate cortices, the emotion produced can be considered, in broad strokes, to be an epiphenomenon of the underlying physical input to the insula, be it pain, thirst, itching, hunger, sexual stimulation, heart beating, or intestinal activity.

The piggybacking of emotions onto physical sensations is the fundamental body mechanism humans have evolved to enhance survival and perpetuation of the species—to find rewards and avoid harm. Emotion is our frontline mechanism for detecting opportunities and threats. On the one hand, emotions can guide us in avoiding harm, for example, as pain and the frequently associated emotion of fear often do. On the other hand, the sensations and their associated emotions can guide us in seeking out opportunities, as sexual stimulation and the associated desire often do.

But the survival responses occur only when the threat or opportunity induces an emotional response of an intensity that prompts action or a decision not to act. In adults, although certainly expressed physically (pain, shaking, crying), emotions more often are expressed verbally as feelings. The expression of feelings becomes more prominent with the development of language, at which point the reliance on physical means to communicate decreases. For example, a five-year-old might say, “I’m afraid,” when his mother leaves for the store, while his one-year-old brother would tremble and cry when she leaves. Language is especially meaningful because it allows greater flexibility in communicating emotional responses to others. This enhances humans’ abilities to better acquire rewards and avoid harm in the crucial social arena where we all must succeed.1

During less threatening (or less opportune) times, the bottom-up processing of physical inputs and the top-down modulating process occur at a subconscious level where they serve a continuous, moment-to-moment monitoring function. In other words, they’re on the lookout for threats or opportunities. Monitoring integrates past experiences of pain (or other physical sensations) and the associated emotion. This includes how it has changed over time, thus enabling the individual to predict what emotion is associated with the pain (or another sensation) based on prior experiences. One’s prior experiences with the sensation determine the emotional response at any given time.

Many believe the chronic pain problem can be explained by atypical associations with pain learned subconsciously during growth and development. These associations differ from the more typical learning experiences of pain seen in patients without chronic pain. Chronic pain can stem from an altered top-down impact on the insula.2,3 Here’s how this might happen. Much emotional expression, including that associated with pain, is socially constructed during childhood.4 That is, we learn what pain means, which gives rise to its associated emotions and thoughts. For example, the joyful feeling of being cared for may be associated with pain when, for example, the child learned that the only way to receive attention was to have a headache or stomach ache—a pain-joy mix. Alternatively, the unpleasant feeling of fear may be associated with pain when the pain was learned during repeated physical abuse in a child—a pain-fear mix. In either case, pain is learned subconsciously from repeatedly atypical situations and such patterns are common in the unfortunate chronic pain patient.

Well outside the range of normal experiences, such repeated, undue focusing on pain during growth and development may, in turn, interrupt the transition from the normal physical expression of emotions in infancy and early childhood (crying, cooing, smiling) to the verbal expression of emotions and feelings when language develops.5 Not only does the patient learn to focus on pain to meet their immediate needs, but they also forgo complete development of the capacity for expressing the emotions they associate with pain by healthier language means. For example, as adults, they might experience chronic back pain as a way to obtain others’ attention because they did not learn to express their needs and emotions through language, a condition called alexithymia, an absence of language for emotional states.6

Although chronic pain certainly is maladaptive in society, rather than considering it a disease, many chronic pain patients are using pain as an adaptive mechanism. Their pain is acting to offset perceived threats to their body integrity and survival. They are using the universal emotion-based survival pathway in an atypical, over-determined way to best achieve rewards and avoid harm. While this understanding may not apply to all patients, such as those with objective hyperalgesia, this prominent pattern is common.

Of what therapeutic significance is this aberration in man’s survival pathway? Our research group has developed the evidence-based Mental Health Care Model (MHCM) for chronic pain patients and others with mental health disorders.7,8 The MHCM places the clinician-patient relationship foremost by using an evidence-based, behaviorally-defined patient-centered method.7 Being patient-centered is especially relevant to those with chronic pain because they frequently have poor relationships with many in their lives—including their clinicians. Further, their ideas about the origin, evaluation, and treatment of chronic pain often must be modified before improvement can occur. The MHCM employs cognitive-behavioral and motivational principles to achieve the necessary re-casting of ideas, for example, convincing them that they do not need surgery, that more tests are not necessary, or that opioids are not an effective treatment. Next, the MHCM uses antidepressant medications for the very common associated problems such as depression and anxiety. Finally, exercise, physical therapy, increased social interactions, working with significant others, and relaxation procedures are key parts of the negotiated program.

Treatment can be effective but, to make it so, we must not expect chronic pain patients to improve by applying the standard medical approach of giving a medication on the presumption they have a disease. Rather, treatment is not simple and takes considerable time—along with patience on both the patient’s and the clinician’s part. We must understand that the chronic pain patient is doing the best they can to survive, but they exist in a stress-inducing medical world where we expect everyone to have a disease that responds to a medication. When our patients do not have a disease, care is more complicated and requires a greater understanding of the origin of their problem.

References

1. Craig AD. Significance of the insula for the evolution of human awareness of feelings from the body. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2011;1225:72-82.

2. Di Lernia D, Serino S, Riva G. Pain in the body. Altered interoception in chronic pain conditions: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016;71:328-41.

3. Craig AD. Pain mechanisms: labeled lines versus convergence in central processing. Annu Rev Neurosci 2003;26:1-30.

4. Barrett L. How Emotions Are Made -- The Secret life of the Brain. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; 2017.

5. Schore AN. Affect Regulation & the Repair of the Self. New York: WW Norton & Co.; 2003.

6. Levenson J. Textbook of Psychosomatic Medicine. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing Co., Inc.; 2005.

7. Fortin VI AH, Dwamena F, Frankel R, Lepisto B, Smith R. Smith's Patient-Centered Interviewing -- An Evidence-Based Method. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, Lange Series; 2018.

8. Smith R, D'Mello D, Freilich L, Osborn G, Laird-Fick H, Dwamena F. Essentials of Pschiatry in Primary Care: Behavioral Health in the Medical Setting. New York: McGraw Hill, Inc., in press; 2019.