Attention

The Science of Misdirection

Netflix's 'Lupin' shows how people can be tricked due to limits in perception.

Posted June 21, 2021 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- The lead character in Netflix's 'Lupin' is a thief who uses many techniques with a basis in cognitive psychology.

- People often can't describe the details of common objects because they never encoded the details in the first place.

- The technique of misdirection is enabled by the fact that when our attention is drawn one place, it is drawn away from everywhere else.

The Netflix series Lupin released its second set of episodes earlier this month. The French series about a charming and elusive thief and con artist, Assane Diop, was a global hit when it originally debuted in January, becoming the first French series to land on the U.S. Netflix Top 10 list. The show's appeal is clear: It has a charismatic star in Omar Sy, a compelling narrative involving conspiracy and revenge, and a lot of heists—like at least one heist (or maybe a caper) per episode.

One of the most pleasing aspects of Lupin is watching the clever ways that Assane executes his plans. Rather than relying on high-tech gadgets or elaborate disguises, Assane usually deploys his astute understanding of psychology, frequently exploiting other people's limitations of perception and attention to avoid recognition and capture. A close look at some of his tactics reveals a deep understanding of human cognition.

(Some minor spoilers follow.)

We can't recall what we never saw.

In one episode, Assane boldly confronts the victim of his most audacious heist to date—stealing a necklace that once belonged to Marie Antoinette from the Louve—in broad daylight. He arrives at the meeting in a public plaza dressed as a courier in a brightly colored uniform. Despite being under watch by the authorities, Assane manages to escape by biking away just as about a dozen identically dressed couriers arrive at the same location.

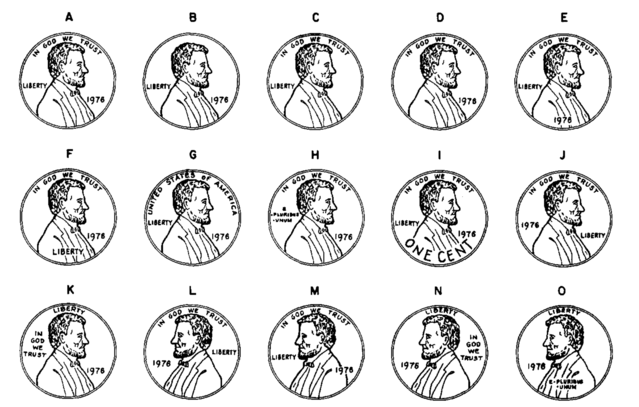

This scene reminded me of one of my favorite memory studies, published in 1979 by Raymond Nickerson and Marilyn Jager Adams. The purpose of the study was to examine memory for common objects; they focused on the U.S. penny. In one experiment, 36 students saw 15 drawings of pennies, only one of which was correct. The students were asked to pick one that they thought was most likely to be correct and group the rest into three categories: ones that they could easily believe were correct, ones that might be correct, and ones that they were sure were incorrect.

The correct drawing was chosen as the most likely one by 15 out of 36 of the subjects, but they were pretty uncertain. Five subjects placed the correct drawing in the "surely incorrect" category. And overall, according to the researchers, "about one-quarter of the drawings, on average, were judged as easily believed to be correct, [and] one quarter were judged as conceivably correct." Just like my own students when I repeat this study informally in my classes, it's clear that many students were basically guessing.

This is an old study with a small sample size, but it's been replicated in various forms over the years. In one version, 120 students were asked to find the correct layout of digits on a phone keypad. The overall results were the same: "only half of the participants recognized the [correct] telephone layout and 12 percent called it 'definitely incorrect'… In addition, a considerable number of incorrect layouts were called 'possibly correct.'"

What these studies show is that even for things we see nearly every day, we often don't bother to encode many of their details into memory unless we need to. Unless your job is to identify counterfeit coins, all you need to be able to do is tell a penny from a quarter, and you can do that by recognizing maybe two or three key features.

Assane clearly understands this. Despite the fact that most of his courier decoys don't really look like Assane in terms of height, skin color, or facial features, the police watching likely only encoded the most salient detail about his appearance: his outfit. As a result, the decoys all looked essentially identical to Assane—just like many of the incorrect penny drawings look perfectly plausible to most of us who never bothered to pay much attention to the details of a penny.

We don't notice what we aren't paying attention to.

Assane also frequently makes use of various forms of misdirection. One example comes from his necklace heist, in which he uses a skirmish as a cover to swap the true necklace for a fake one.

The effectiveness of misdirection exploits the limits of our attentional capacity: We can't pay attention to everything. And when someone deliberately draws our attention one way, they also draw our attention away from everywhere else, giving them the opportunity to do something where we're not paying attention.

A straightforward demonstration of how our attention can be cued in this way comes from a classic experiment by Michael Posner, Mary Jo Nissen, and William Ogden. In the experiment, subjects saw many trials in which an arrow briefly appeared on the center of the screen pointing left or right, followed by an X on either the left or right side of the screen. Subjects had to press a key indicating which side of the screen the X was on. Eighty percent of the time, the arrow pointed in the direction that the X would appear, and 20 percent of the time, it pointed in the opposite direction. The experiment included only six subjects, but each subject completed nearly 400 trials.

The researchers found that, on average, when the arrow pointed in the incorrect direction, subjects were about 100 ms slower to respond than when the arrow pointed in the correct direction. They also made many more errors, for example, by pressing the "left" key when the X was on the right. These results demonstrate a kind of misdirection: When people aren't expecting something, they're slower to notice and react to it.

Magicians have known these things for centuries.

Lupin is a fictional show, but many of the techniques Assane employs in it are very real. Indeed, misdirection and a deep (if implicit) understanding of cognition are key components to being a successful magician. This point has been made by psychologist Gustav Kuhn and his colleagues, who have argued that cognitive scientists potentially have much to learn by studying magicians' methods.

Lupin shows us that understanding how a trick is done doesn't make it less of a pleasure to watch, especially when it's performed by a master of the craft.