Philosophy

Resisting the “Me” Culture Can Lead to Greater Fulfillment

Self-denial can offer more freedom and fulfillment than self-indulgence.

Posted August 28, 2024 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- We live in a culture that promotes self-care, self-affirmation, and self-fulfillment at all costs.

- Paradoxically, this effort to constantly make ourselves happy tends to makes us unhappy.

- The great philosophers, religions, and wisdom traditions have always taught self-discipline and restraint.

Plutarch tells the story of the meeting between Alexander the Great, one of history’s most revered conquerors, and Diogenes of Sinope, one of its most ridiculed philosophers. Upon arriving in Corinth, Alexander was greeted with cheers and adulation. He was visited by every reputable person in the city—everyone, that is, but Diogenes.

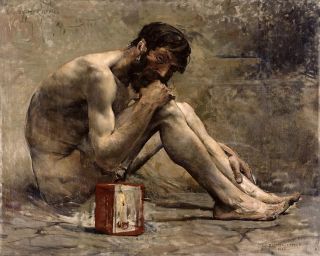

Irritated by the slight, Alexander went out looking for the famed contrarian. He found him, as Diogenes was wont to be, lying pale and malnourished on the ground in the marketplace. Wishing to emphasize his magnanimity and thus his superiority, Alexander walked up to the reclining philosopher and offered to grant him anything he wished.

What was Diogenes’ response? “Stand a little out of my sunlight.”

The audacity of such disinterest evinces a kind of personal freedom found rarely among humans. Who would dare look into the eyes of the most powerful man in the world and yawn? That Diogenes was capable of doing so highlights something peculiar about how he chose to live his life.

While most of us are motivated by wealth, prestige, and comfort, Diogenes scorned every worldly pursuit and thereby found himself liberated. Only someone who has forsworn the trappings of pleasure and personal advancement could manifest such cheerful irreverence in the face of ambition and power.

For Diogenes, self-denial was more than a philosophy. It was a way of life. He never tired of finding opportunities to point out his own folly and the abject absurdity that governs human affairs.

Knowing, as we do, that we are all destined to die, how is it that we spend our days toiling away, amassing wealth that will not save us in the end? Recognizing that the effects of time and age are unavoidable, why do we strive for beauty and cling desperately to our fleeting youth? Seeing that even a king is only a man, subject to the same pangs and humiliations as all of us, why do we chase fame and honor in the eyes of the world? Understanding that our advantage is often bought at the expense of others, fellow sufferers on the same road to the grave, why do we prize comfort over care for those around us?

There is, of course, a different path, one as unpopular in Diogenes’ day as it is in our culture of “Me,” which preaches self-affirmation and self-fulfillment at any cost. Instead of striving to fulfill oneself, a notoriously elusive task, one might try denying oneself, finding small ways to chasten one’s ambitions and restrain one’s desires.

It is no accident that nearly every religion and all of the great wisdom traditions preach temperance and moderation. To master oneself is a harder task than to conquer the world. Unlike Alexander—whose pursuit of self-deification led him to raze cities and destroy whole populations—statues are not built to honor, history books are not written to commemorate the lives of those who war with themselves.

Self-denial can, of course, be taken to unhealthy extremes, which is why in addition to reserving certain periods during the year for fasting, most religions also commemorate holidays with bountiful feasts. But in a world that incessantly encourages us to chase our desires and strive to follow whatever means we believe will lead us to happiness, the risk is not that we become overzealous in our asceticism. Rather, we are being bombarded daily with advertisements that prey upon our culture’s commitment to notions of self-expression and self-creation. What could be more countercultural, then, than to resist this onslaught of narcissistic “Me-ism” by giving up—in small, often unrecognized ways—some of the things we want?

Doing so, paradoxically, can lead to the very fulfillment we have been looking for by enabling us to turn our gaze beyond ourselves and thus see and better appreciate life around us. It’s hard to care for others when we’re constantly being told we must take care of ourselves. It’s hard to enjoy another’s success when we view that other as a possible rival. But when we train ourselves to give up what we want, we often find that we’re more attuned to the needs of our friends, families, and neighbors, more grateful for all that we do have, all that we already are.

One can imagine a proud man like Alexander losing his temper with the playful ribbing of Diogenes the fool. That, however, is not what happened. Plutarch tells us that in response to the philosopher’s irreverent jibe, Alexander said, “Truly, if I were not Alexander, I wish I were Diogenes.”

An acknowledgment, perhaps, that it means very little to gain the whole world when one has not mastered one’s own soul; and a helpful reminder to all of us that true freedom comes not from amassing power and wealth but from forgoing them.

References

The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. A Peer-reviewed academic resource. Diogenes of Sinope (c. 404—323 B.C.E.)