Motivated Reasoning

How Russia's Propaganda Really Works

It's not just by "brainwashing" people.

Posted March 18, 2022 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Propaganda about facts is only effective to the extent people want to believe it.

- Propaganda can be very effective in triggering nationalist emotions which increase the support for the regime.

- Propaganda is also effective against opponents by confusing and dividing them, thereby limiting their cohesion.

It is common to think of propaganda as filling the brain of naive recipients with a purposely distorted view of reality. In this view, brute repetition generates conviction in the population. This top-down vision, however, is not how propaganda really works. People have agency, they are not mere receptacles of external information. Even in one of the most totalitarian states of the 20th century, Nazi Germany, people were deeply skeptical of the propaganda. A note from the Nazi intelligence agency, quoted by Hugo Mercier, stated candidly: "Our propaganda encounters rejection everywhere among the population because it is regarded as wrong and lying."

But propaganda does work, in some ways. Western observers have been dismayed to find out that the Russian invasion of Ukraine is most likely supported by a majority of the Russian population. The regime’s propaganda has played a decisive role in getting this support.

How propaganda works: fostering support for the regime

One of the simplest but most profound truths about propaganda is that it works for people who want to believe in it. In psychological terms, propaganda offers what looks like facts and overall narratives which can feed people’s motivated reasoning. Motivated reasoning is ubiquitous, it is our tendency to treat evidence selectively to justify beliefs that conveniently align with our preferences. We routinely engage in motivated reasoning when having to assess whether our beliefs are right, whether our work deserves more recognition, or whether something we did was right or wrong. When having to think about whether their country is in the right, citizens have a preference to think it is. Propaganda can be effective because it provides justifications that people want to believe in to start with.

Because propaganda works with motivated reasoning, it works best when the regime can foster feelings among its citizens of national identity. Feelings of group identity can be very strong and are particularly fierce when members of a group are in conflict with another group. In that case, cooperation increases within the group while aggression increases towards the other group. By fostering closer bonds within the country, nationalist feelings help support a regime leader whose decisions are less likely to be questioned. This rally-around-the-flag effect is well-known to favour leaders who see their support increase in times of war, at least initially.

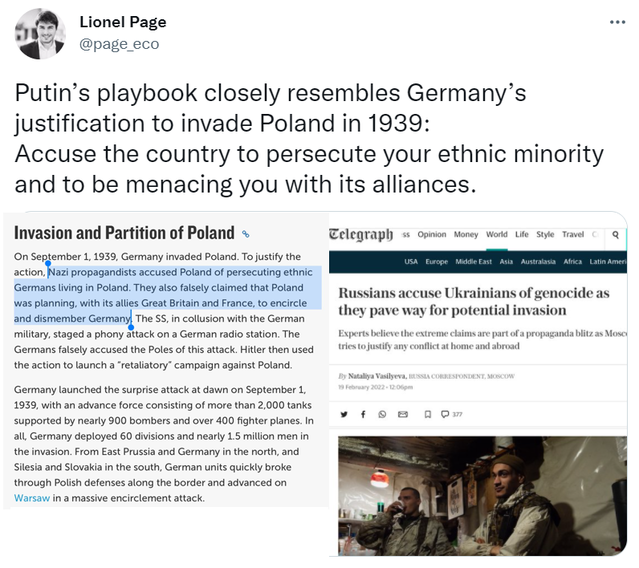

A key goal of propaganda is to stress an “us vs. them” narrative with the recanting of grievances towards an outgroup, the propping up of actual or fabricated slights or aggressions from outside. It is therefore a usual tactic of an aggressive country to claim it is actually the victim. Such a message can have a strong emotional impact on the population and foster its willingness to accept the government’s propaganda.

In a situation where a regime does something likely to be unpopular with its people, like the current invasion of Ukraine, propaganda can channel citizens through three steps of rationalisation: denial, minimisation, and justification.

In the denial phase, the propaganda can help citizens reject the factual evidence and believe that it is not happening: “There is no war, it is a limited operation.” In the minimisation phase, as factual evidence gets harder to reject, propaganda may help citizens minimise the problem: “There is a conflict but it is limited.” Finally, in the justification phase, propaganda can help citizens progressively accept and support the new reality: “There is a war but it was needed.”

A pessimistic take from this understanding of propaganda is that changing a population's factual perception is not necessarily enough to generate massive opposition to a regime in a situation like the invasion of Ukraine. It is not necessarily the case that Russians will disapprove of the war when the evidence for its reality becomes unquestionable.

For propaganda not to work, the engine of motivated reasoning needs to break. This happens when the costs (human and economic) of the conflict increase to the point where individuals’ personal interests conflict with the war campaign itself. In that view, the quick-round-the-flag effect which happened after the invasion and the jingoistic support which was on display in many quarters of the Russian society may progressively crumble when the huge costs of the war progressively down unto Russian citizens.

How propaganda works: incapacitating oppositions

Propaganda is also strategically useful to incapacitate opposition, within and outside the country. A key insight here is that collective actions—such as people protesting against the regime within the country, or external countries deciding on sanctions—require successful coordination.

Let’s consider popular protests. It is common to hear people say, “Why don't Russians protest? They could topple the regime.” This intuition may seem compelling. In a modern state like Russia, a massively large crowd of protesters, in the hundreds of thousands, would be very hard to stop or to crack down on.

But opposition to an authoritarian regime is risky. You can be arrested, lose your job, be beaten, or disappear for good. So, while massive protests can be successful, small protests can be very costly for participants. Opponents face a coordination problem: if they are confident that others will protest, they should protest. If they are not confident, protesting may be too risky.

Similarly, other countries considering sanctions need to coordinate to do so. Sanctions are costly. Some countries will be more impacted than others. In the case of sanctions against Russia, Germany is heavily reliant on Russian gas, while the U.K. has seen a tremendous accumulation of Russian wealth in London. Sanctions require a high level of consensus to be effective either because they are decided collectively (e.g., at the E.U. level) or because they need a large number of countries to participate to be effective. Since countries face different costs of implementing sanctions, they have different criteria to decide whether to join in enforcement

Because opponents to a regime need to coordinate, the regime's propaganda is also used to make this coordination more difficult. In practice, propaganda aims to confuse, divide, and incapacitate possible opponents.

Confusion: As propaganda generates fake narratives, it can help reduce the certainty of the public opinion within the country and in other countries about the truth. It is harder to be angry at something when one is not sure whether this something is happening or not. Hannah Arendt famously said that the ideal subject of a totalitarian state is somebody for whom the distinction between true and false no longer exist. Within the country, where the regime can control public communications, confusion even works at a more subtle level. Even if you do not believe the propaganda, you may fear that others may believe it. You may therefore opt not to protest because you fear not enough other people would. In the end, even if a large number of people would be willing to protest, only a few may opt to do so. In game theory, a key strategic aspect of coordination games is whether opponents have common knowledge: the knowledge that others agree with them and that they know you agree with them. By simply monopolising the public space of public communication, an authoritarian regime prevents such common knowledge to arise.

Division: In addition to this confusion, propaganda may divide potential opponents. Any group of potential opponents, whether potential protesters inside the country or foreign nations considering sanctions, have varying levels of disagreement with the regime and face different costs in opposing the regime. For the opponents who face the greatest costs in being antagonistic, propaganda can facilitate for them the possibility to engage in motivated reasoning in favour of the regime. This mechanism can allow the regime to peel away subgroups from an otherwise cohesive opposition.

Incapacitation: In the end, this conjunction of confusion and division can lead to the incapacitation of the opposition. Inside the country, thousands of people may opt not to take to the streets en masse. In external countries, leaders and public opinions may be divided on the interpretation of events. False flag operations, used to blame the victim prior to aggression, can, in particular, be particularly effective at creating confusion in other countries and limiting their ability to take a clear stance.

In conclusion, propaganda can be very effective. Counterintuitively, it works with the regime supporters because it relies on their will to be convinced, and it works with potential opponents not by convincing them but by making the limits between truth and falsehood blurry, in a way that hinders their reaction. What makes the strength of propaganda also predicts how it fails: when people stop thinking that the regime is good for them, propaganda progressively falls on deaf ears.

References

Mercier, H., 2020. Not born yesterday. Princeton University Press.

Epley, N. and Gilovich, T., 2016. The mechanics of motivated reasoning. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(3), pp.133-40.